Few people figure in the story of Silicon Valley as prominently as Steve Jobs. After co-founding Apple in 1976, Jobs was famously fired from the company in 1985. His Shakespearean return, saving Apple from near-bankruptcy and setting it on the path to become one of the world’s most highly valued companies, has become one of the great American success stories.

Now, a decade after Jobs died on Oct. 5, 2011, at the age of 56 from pancreatic cancer, his shadow still looms large over the tech world. His ability to tie emotional stories to his company’s products, which he would reveal during splashy product launches that typically ended with “one more thing,” is widely emulated by executives at companies big and small. As are his top-down leadership style and obsession with secrecy. Some have even adopted their takes on his trademark uniform: black mock turtleneck, jeans and New Balance sneakers.

None of these traits is unusual for an entrepreneur, harking back to the one who built a company that created some of the world’s most influential tech products, including the iPod, iPhone and iPad. Disruptive innovators are often driven to do something different and to test conventional wisdom. And Jobs certainly did that.

“They’re working on things that aren’t just another continuous step,” said David Hsu, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School who focuses on entrepreneurial innovation and management. “When it comes to innovation in Silicon Valley, it’s this kind of ‘We’ll follow something off the beaten path.'”

The less-trodden path can sometimes lead to failure, as it did for Jobs in 1985, but it’s one that other Silicon Valley execs have vowed to follow.

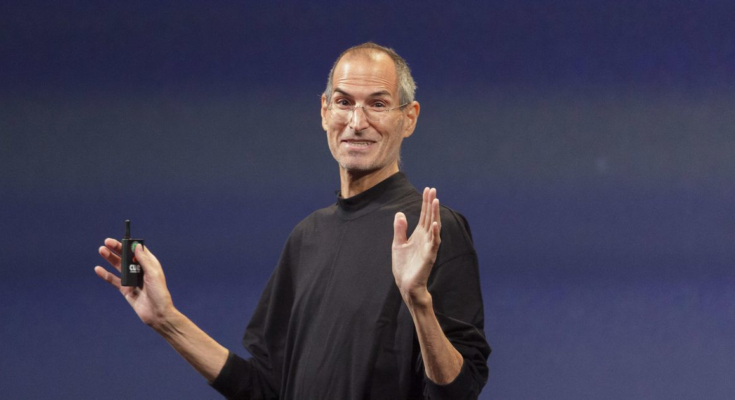

Jobs showed off Apple’s first iPhone during a keynote presentation at the Macworld Conference in San Francisco in 2007. Apple, he said, was “going to reinvent the phone.”

James Martin/CNET

His legacy is burned into the backs of the minds of people who feel that success comes first, regardless of niceties or wrongdoing. Sometimes, employees or mentors might think they’ve found the next Jobs-like figure to become a titan of industry, creating the next Apple. In their search, though, poor decisions, bad behavior and fraud have festered, sometimes overlooked. Brilliant and charismatic, if flawed, founders have led companies to meteoric rises, and equally shocking flameouts once they came under scrutiny. Like Hollywood celebrities, a superstar CEO can rise quickly only to fall spectacularly when egregious missteps draw attention. And they could be ruining it for everyone else.

“I keep thinking, is there a way where instead of a brilliant jerk, you can have a brilliant humble game-changer in society?” Hsu said. “We need to hold up and recognize there are many pathways to success and many different ways to contribute.”

Steve Jobs didn’t live to see Apple’s new headquarters built in Cupertino, or the presentation theater (above) that bears his name.

James Martin/CNET

The next…

For all the wealth, power and success that the tech industry has generated, it’s increasingly littered with false messiahs who weave stories filled with lies, confuse truth-telling brashness with invective, and rely on secrecy not for the drama of the grand reveal, but as a way to cover up wrongdoing.

Perhaps the most egregious is the blood-testing startup Theranos, where CEO Elizabeth Holmes fashioned herself as the heir apparent, a tech leader on a grand scale, surrounded by a mix of hype and secrecy, and often appearing in a black turtleneck uniform. She started the company in 2003, and dropped out of Stanford at 19. A decade later she was being hailed as the next big thing.

“This CEO is out for blood,” Fortune wrote on its 2014 cover story about Holmes and “her secretive company” that “aim to revolutionize healthcare.” Wired called the implications of her work “mind-blowing.” And Inc. magazine declared Holmes “The Next Steve Jobs.” All the while, Holmes reportedly lied to investors, business partners and customers about the capabilities and accuracy of her company’s machines. She’s currently on trial for wire fraud and conspiracy to commit wire fraud.

Theranos CEO Elizabeth Holmes posing for a photo in the documentary, The Inventor: Out For Blood in Silicon Valley.

HBO

Other executives didn’t copy Jobs’ personal style, but they were given leeway despite their flaws all the same. At Uber, there was widespread sexual harassment and bro culture behavior inside the ride-hailing service up to and including its co-founder Travis Kalanick. In 2014, when he was Uber’s CEO, Kalanick bragged about how much of an eligible bachelor he’d become, telling GQ, “Yeah, we call that Boob-er.”

Shared-office company WeWork delayed its IPO in 2019, after public financial records reports showed the company bleeding cash. As did the bro culture at Uber, WeWork CEO Adam Neumann’s behavior came under scrutiny, particularly for his drug use, alcohol-soaked parties and the cultish undertones to his company’s work culture.

“Tech investors generally don’t care about allegations of fraud, harassment or discrimination, especially if they can profit from it,” wrote Ellen Pao, a tech investor and head of the diversity- and inclusion-focused Project Include, in the New York Times last month. In 2015, she lost a high-profile court case against her former employer, the storied venture firm Kleiner Perkins, over sexual discrimination and retaliation. “These problems can’t be ignored or pretended away. If the members of the investors’ boys’ club won’t hold each other accountable, prosecutors must step in.”

Jobs, of course, isn’t responsible for any flawed CEO or for the culture that tolerates their behavior. And people do bad things far beyond the tech world. But today, as questions swirl about Silicon Valley’s power amid increasing calls for regulation and punishment, the unspoken search for the next Jobs-like figure is becoming a cautionary tale that few seem to have learned from.

Jobs was a gifted story teller.

James Martin/CNET

Gifted storytelling

For decades, the Silicon Valley hero saga has served as a modern version of the American dream. And with good reason. When Jobs started Apple with Steve Wozniak and Ron Wayne in the late 1970s, the US was coming out of a period of intense uncertainty. During that decade, the US pulled out of the Vietnam War, while inflation and oil prices skyrocketed. Foreign manufacturing was heating up as well, just as the country’s manufacturing base began its decline.

“Jobs emerges at this moment as an utterly different type of business leader,” said Margaret O’Mara, a professor at the University of Washington and author of The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America. He wasn’t like the CEOs of big business that had fallen out of favor, nor was he a typical computer nerd of the time.

One key quality Jobs possessed was a gift for storytelling, O’Mara said, which inspired people to think about what computers could do at a time when most people considered them mere machines. Long before Google or the public Internet, Jobs talked about how networked computers will “have the entire Library of Congress at our fingertips.” He talked about video games not as trivial wastes of time, as many parents did, but as “simulated learning environments” where “the more you learn the underlying principles, the better your score.” He would often call computers “a bicycle for our minds.”

That inspiration continues to pulse through the tech industry today. When he announced the iPhone 13 last month, Tim Cook, Jobs’ hand-picked successor, said Apple is “designing the very best products and services to enrich people’s lives.” Microsoft’s product chief, Panos Panay, talked of how his company’s Windows software is “a home for billions of people to do their jobs, live their dreams and connect with the people they love.” Amazon’s head of devices and services, David Limp, meanwhile, showed off his team’s “next big leaps forward; science fiction becoming reality.”

Uber, WeWork and Theranos had their stories, too. Uber talked about how its software didn’t just connect drivers and riders, it was changing how we move around cities, while giving people a new way to make money as drivers. WeWork was creating spaces amid a “profound change in technology, demographics and urbanization” that, naturally, was encouraging more “flexible, entrepreneurial and collaborative work styles,” according to one of its early investor presentations.

Theranos, a name made from the combination of the words “therapy” and “diagnosis,” created ads for its finger-prick blood-testing service, promising that “one tiny drop changes everything.”

“What do you dream for?” an interviewer once asked Holmes. “That less people have to say goodbye to the people they love,” she said.

An impromptu memorial at the Apple Store on Stockton Street in San Francisco for Steve Jobs on the night of his death, Oct. 5, 2011.

James Martin/CNET

Brash and secret

It’s hard to point to why so many intelligent people throughout the tech world tolerate bad behavior on such a large scale — and for so long. Some tech employees say they’ve been blinded by the promise of riding the rocket ship of success, which inevitably has some bumps along the way. Others say the magnetic personalities of CEOs warp how people see themselves and the world around them.

There’s also the Jobs story itself. Fired from Apple following a power struggle with the company’s board and then-CEO John Sculley, Jobs, then 30, was known for his fiery temper and obsession with cultivating mystery about the next big thing Apple was working on by siloing teams and swearing them to secrecy. He worked like crazy and expected it of everyone else.

“I felt that I had let the previous generation of entrepreneurs down — that I had dropped the baton as it was being passed to me,” Jobs said, reflecting on that time, during a Stanford University commencement address in 2005. “It was awful-tasting medicine,” he said of being fired, “but I guess the patient needed it. Sometimes life hits you in the head with a brick.”

Even after Jobs returned in 1996, he was known for his brashness. He fired some Apple employees mere moments after meeting them in an elevator. In 2006, when he joined the board of Walt Disney as its largest shareholder, Jobs reportedly introduced himself to the head of ESPN by saying, “Your phone is the dumbest fucking idea I have ever heard.” (ESPN at the time was offering branded phones and wireless plans, which were all the rage back then.)

The exchange, captured in the book Those Guys Have All The Fun: Inside the World of ESPN, ended when Jobs turned and walked away. Disney reportedly lost $135 million on its Mobile ESPN venture that year.

“He was definitely a truth-teller,” said Eric Schiffer, brand management expert and chairman of Reputation Management Consultants, who makes a professional study of industry-defining CEOs as he helps corporations and celebrities build their brands.

To Schiffer, the key was that Jobs was choosing “truth over pleasantries.” By comparison, he said the bad behavior of some executives throughout Silicon Valley ignores that Jobs was often pushing his engineers to think of the human beings they were building machines for. “That’s where most people fail,” he added.

“I don’t think his intention was to be a jerk,” Schiffer said of Jobs. “His intention was to tell the truth and crack the mold, and have a hyper-high standard that if you didn’t meet that, he was going to let you know.”

Revelations about the bro culture Travis Kalanick oversaw at Uber caused a reckoning in the tech industry.

James Martin/CNET

Changing course

Silicon Valley’s reckoning with its leaders, their behavior and its own image has led to some changes. Many large companies, including Apple, Google, Microsoft and Facebook, started releasing regular reports about diversity and inclusion efforts within their employee bases in the past seven years. They’ve also begun deemphasizing their CEOs on stage during presentations and in product releases, giving face time to more women and people of color who worked on and led teams within the company.

Still, problems persist. Apple’s come under unprecedented pressure from employees, who say the company’s obsession with secrecy — instilled since the days Jobs was in charge — made people terrified to blow the whistle on bad behavior and allowed a hostile work environment to grow.

Criticism of Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, whom Jobs mentored before he died, has grown for his obstinance about changing the fundamental ways his social network has moderated content in the face of election interference, mass harassment campaigns and vaccine disinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even Kalanick channeled the tech industry’s lenient nature after he was ousted as Uber’s CEO in the summer of 2017. He reportedly told several people at the time he was “Steve Jobs-ing it,” according to reporting from Recode, expecting to return in triumph even though he was fired.

Hsu, the professor at Wharton, said these issues are being talked about in academic circles, including at his alma mater, Stanford — where many Silicon Valley founders, from Google’s Larry Page and Sergey Brin to Theranos’ Holmes, got their start.

Hsu has been altering his curriculum to include case studies and situations that raise ethical questions and conversations. He also draws attention to lesser-known tech executives known for their positive impact, like Sal Khan, who created the nonprofit Khan Academy in 2008 to publish educational tutorials for free on the web.

“We need a broader recognition of what it means to be successful,” Hsu said. “Social impact and making a difference, and achieving that in a myriad of ways — you don’t have to be the jerk. There are many different narratives that can be the model.”

Jobs may not have fully agreed. He once said, “If you want to make everyone happy, don’t be a leader, sell ice cream.”

But he also preached doing the work you love. “Don’t be trapped by dogma — which is living with the results of other people’s thinking,” he said during that Stanford speech in 2005. “Don’t let the noise of other’s opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition.”