In 1998, Donna Dubinsky and Jeff Hawkins quit Palm, a company they’d founded, to begin a new one: Handspring. They had a simple goal in mind: to eventually create the smartphone. Years before any of the technology was actually ready, their tiny startup began laying the necessary groundwork for what would become the Treo.

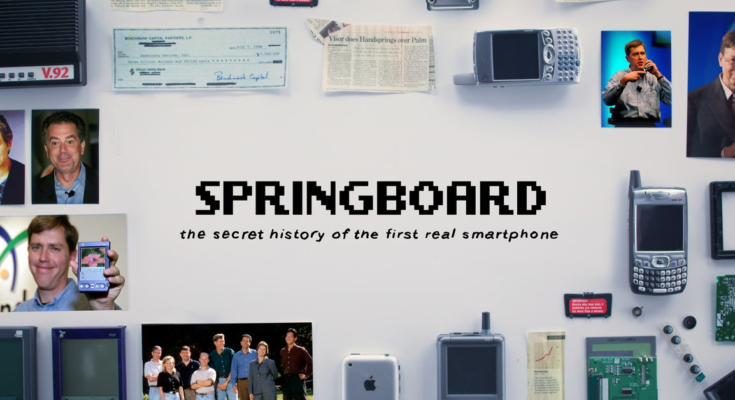

In Springboard: the secret history of the first real smartphone, we document the history of Handspring, from its dramatic beginnings to its tragic end. Along the way, we hear from five of the key players who tried to invent the modern smartphone years before the technology world was ready for it. It’s a story that interweaves the dotcom crash, technological innovations, wireless carrier resistance, and much more.

You can watch Springboard on The Verge’s smart TV apps on Roku, Fire TV, Android TV, and Apple TV. And now it’s also available on our YouTube channel.

Alongside today’s YouTube release, we’re also publishing a special episode of The Vergecast, the discussion we recorded after the premiere of Springboard at our 10-year anniversary party in New York last October. In it, Nilay Patel and I talk through some of the stories that were left on the cutting room floor.

I’d like to share a couple of them here, too. Both fall outside the scope of the documentary’s timeline, which was focused strictly on Handspring and not the eras of Palm that preceded and followed it.

The first comes from Jeff Hawkins during the early days of Palm. His company had captured the lion’s share of the Personal Digital Assistant Market with the PalmPilot and some of its successors, which meant that Microsoft was going to take another run at them. Given Microsoft’s dominance, it was an existential threat. Here’s how Jeff, one of the great product executives in tech history, described his approach to handling that threat:

Our first big run in competition was with the Palm V. That was with Microsoft.

We had been having a lot of success with the PalmPilot, and Microsoft said, literally, Steve Ballmer got in front of their annual conference, and they had a picture of Palm in a target, and it was like, “We’re gonna kill these guys,” you know? “We’re gonna crush them.”

I had engineers writing their resumes. I mean there were people saying, “Oh, man, it was a good run, sorry,” you know? The conventional wisdom was you can’t compete against Microsoft, and I said, “No, we can compete.”

And I came up with a strategy for it. I said we’re gonna build hardware and the software. They’re only building the software, and they’re relying on other people to build the hardware. So what we oughta do on our next product is create the most beautiful piece of hardware we can create, which they’re not gonna do.

This was the controversial idea; they were adding all these features to their software, tons of features to their software. And I said, “We’re not gonna add any new features to our software,” because if we add new features to our software, people are going to compare our new software features to Microsoft’s new software features, and we’re gonna be behind.

If we come out with a beautiful product, they won’t talk about our new software features. All they’ll do is talk about the new, beautiful product. And then they’ll say, “This product is more beautiful than anything that they got going on,” right?

So this was a controversial strategy of mine; we’re not going to add new features when the Palm V came out. There’s going to be no new software features. We could have had a whole list of things we could put in, but I said that’s not going to help us. And it worked beautifully.

The Palm V came out, and we just crushed Microsoft. They just, you know, they just couldn’t compete at all. And they were blown away that we blew ‘em away.

The second story is a little different — and it’s also addressed in our Vergecast episode today, with some of the relevant audio. After Handspring merged back with Palm, Ed Colligan was running things, and eventually, all eyes were on Apple, which was widely expected to release a smartphone. A few weeks before the iPhone was first announced, Colligan sat for an interview with New York Times reporter John Markoff at the Churchill Club.

Back in 2006, nothing had actually leaked about the iPhone, and so Markoff and Colligan speculated a bit on what Apple might be doing. Then the conversation turned to discussing competition in general.

All of this context is in service to correcting the record on one of Colligan’s responses. Somewhat famously, a line of his has been quoted over and over — most often by John Gruber at Daring Fireball in a post titled “Palm CEO Ed Colligan’s Head Seems to be Stuck Somewhere.” He quotes the following real-time transcription — which, as it turns out, is inaccurate:

Responding to questions from New York Times correspondent John Markoff at a Churchill Club breakfast gathering Thursday morning, Colligan laughed off the idea that any company — including the wildly popular Apple Computer — could easily win customers in the finicky smartphone sector.

“We’ve learned and struggled for a few years here figuring out how to make a decent phone,” he said. “PC guys are not going to just figure this out. They’re not going to just walk in.”

We’ve gotten the original recording of the interview — our thanks to the Computer History Museum, which has received the Churchill Club’s archives after it sadly had to shut down. Here’s the actual exchange, which begins after the Apple speculation.

John Markoff: But what will it look like in 2007? Apple does get in. Eric’s [Schmidt, then CEO of Google] wandering around talking about free phones. He’s got Andy Rubin, who was the founder of Danger doing something inside. He bought Andy’s startup. The phone market could look, I mean, it looks crowded now. It could look intensely crowded next year.

Ed Colligan: It’s intensely big. We just have to get our fair share of the pie. And let me tell you this, it’s not as easy as it looks. You’ve seen Motorola, one of the biggest phone companies in the world enter with a device that was going to take over the world, and it’s had enormous issues.

Markoff: The Q? You’re talking about the Q. [The Motorola Q, a hyped up Windows Mobile smartphone that struggled with technical problems and slow sales]

Colligan: Yeah. And so I just would caution people that think they’re going to walk in here and just and do these. We’ve struggled for a few years here, figuring out how to make a decent phone. The PC guys are not going to just, you know, knock this out. I guarantee it. So, look, welcome, let’s go for it. We can’t stop all that. It’s going to happen, but it’s going to be, I don’t think it’ll be so easy for everybody, as everybody thinks to enter it. It’s a tough space.

Markoff: You’ve been around this industry long enough, and you probably remember, maybe you don’t actually, the famous Wall Street Journal ad that Apple took out in 1981. “Welcome IBM. Seriously.”

Colligan: Exactly. Well, look, you know, I’m not trying to be cocky about it. It is a tough, it’s a tough business. We’ve really struggled through that in the sense of making world class radios that perform on global networks consistently with all the applications that we deliver and…

Markoff: Is radio expertise, something you have to have internally, is that…

Colligan: Yes.

Markoff: Yeah. That’s a black art, still.

Colligan: Yes.

The conversation moves on from there. Colligan clearly saw the competition coming was was likely worried and needed to put a brave face on it, but it’s notable that the more immediate prompt was Google and Motorola. And beyond the specifics of the wording, the overall tone and affect of Colligan’s response (which you can hear about in The Vergecast episode, starting around the 11 minute mark) is also relevant. It wasn’t a prediction that Apple would fail — it was more of an admission that smartphones were hard. And it wasn’t simply about Apple, but also Google and the new entrants running Windows Mobile (which Palm also used on its Treos at the time).

Weeks later, the iPhone was announced and it was, of course, more popular than any Treo. However, it was Android that ended up walking in, becoming the fatal competition for Palm and its subsequent webOS phones. Verizon ultimately chose Google’s operating system and the Motorola Droid instead of the Palm Pre to compete with the then-AT&T-exclusive iPhone.

The Motorola Droid was spearheaded by Rick Osterloh — who got his start making SoundsGood MP3 Springboard modules for Handspring Visors before his company was acquired by Motorola. Palm held on for a little while longer and was acquired by HP, but the Droid was the beginning of the end. Osterloh now runs hardware at Google, and his Pixel phones face competition every bit as daunting as anything Palm once dealt with.