T3 Magazine/Getty Images

Academic researchers have devised a new working exploit that commandeers Amazon Echo smart speakers and forces them to unlock doors, make phone calls and unauthorized purchases, and control furnaces, microwave ovens, and other smart appliances.

The attack works by using the device’s speaker to issue voice commands. As long as the speech contains the device wake word (usually “Alexa” or “Echo”) followed by a permissible command, the Echo will carry it out, researchers from Royal Holloway University in London and Italy’s University of Catania found. Even when devices require verbal confirmation before executing sensitive commands, it’s trivial to bypass the measure by adding the word “yes” about six seconds after issuing the command. Attackers can also exploit what the researchers call the “FVV,” or full voice vulnerability, which allows Echos to make self-issued commands without temporarily reducing the device volume.

Alexa, go hack yourself

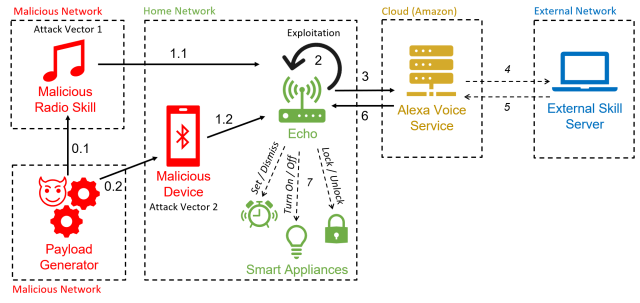

Because the hack uses Alexa functionality to force devices to make self-issued commands, the researchers have dubbed it “AvA,” short for Alexa vs. Alexa. It requires only a few seconds of proximity to a vulnerable device while it’s turned on so an attacker can utter a voice command instructing it to pair with an attacker’s Bluetooth-enabled device. As long as the device remains within radio range of the Echo, the attacker will be able to issue commands.

The attack “is the first to exploit the vulnerability of self-issuing arbitrary commands on Echo devices, allowing an attacker to control them for a prolonged amount of time,” the researchers wrote in a paper published two weeks ago. “With this work, we remove the necessity of having an external speaker near the target device, increasing the overall likelihood of the attack.”

A variation of the attack uses a malicious radio station to generate the self-issued commands. That attack is no longer possible in the way shown in the paper following security patches that Echo-maker Amazon released in response to the research. The researchers have confirmed that the attacks work against 3rd- and 4th-generation Echo Dot devices.

Esposito et al.

AvA begins when a vulnerable Echo device connects by Bluetooth to the attacker’s device (and for unpatched Echos, when they play the malicious radio station). From then on, the attacker can use a text-to-speech app or other means to stream voice commands. Here’s a video of AvA in action. All the variations of the attack remain viable, with the exception of what’s shown between 1:40 and 2:14:

Alexa versus Alexa – Demo.

The researchers found they could use AvA to force devices to carry out a host of commands, many with serious privacy or security consequences. Possible malicious actions include:

- Controlling other smart appliances, such as turning off lights, turning on a smart microwave oven, setting the heating to an unsafe temperature, or unlocking smart door locks. As noted earlier, when Echos require confirmation, the adversary only needs to append a “yes” to the command about six seconds after the request.

- Call any phone number, including one controlled by the attacker, so that it’s possible to eavesdrop on nearby sounds. While Echos use a light to indicate that they are making a call, devices are not always visible to users, and less experienced users may not know what the light means.

- Making unauthorized purchases using the victim’s Amazon account. Although Amazon will send an email notifying the victim of the purchase, the email may be missed or the user may lose trust in Amazon. Alternatively, attackers can also delete items already in the account shopping cart.

- Tampering with a user’s previously linked calendar to add, move, delete, or modify events.

- Impersonate skills or start any skill of the attacker’s choice. This, in turn, could allow attackers to obtain passwords and personal data.

- Retrieve all utterances made by the victim. Using what the researchers call a “mask attack,” an adversary can intercept commands and store them in a database. This could allow the adversary to extract private data, gather information on used skills, and infer user habits.

The researchers wrote:

With these tests, we demonstrated that AvA can be used to give arbitrary commands of any type and length, with optimal results—in particular, an attacker can control smart lights with a 93% success rate, successfully buy unwanted items on Amazon 100% of the times, and tamper [with] a linked calendar with 88% success rate. Complex commands that have to be recognized correctly in their entirety to succeed, such as calling a phone number, have an almost optimal success rate, in this case 73%. Additionally, results shown in Table 7 demonstrate the attacker can successfully set up a Voice Masquerading Attack via our Mask Attack skill without being detected, and all issued utterances can be retrieved and stored in the attacker’s database, namely 41 in our case.