Clockwise from top left: Rachel Brosnahan on Quibi, the virtual audience, Gal Gadot’s “Imagine,” Travis Scott’s Astronomical, Verzuz, “Lose Yo Job,” Animal Crossing, Ziwe’s IG Live show, Megan Stalter, Circle Jerk

Illustration: Ari Liloan

Since the early days of the pandemic, the engines of mass culture have attempted to churn forward. But by mid-March, it had already become clear they were ill-equipped to meet the COVID moment. Big-budget movies, plays, and concert tours were canceled. When TV shows tried to mirror banal realities of the pandemic — framing episodes through Zoom calls, splicing in mask jokes — more often than not, they failed to resonate. Daytime TV started beaming virtual audiences into physical studios, and the result couldn’t help but appear unhinged. The audience faces loomed, their laughs in permanent lag.

The rules for what worked had changed. Instead of fretting over what was lost, some of the most interesting art this year leaned into the immediacy of the internet. That meant celebrating the flattened hierarchies of online gaming and Instagram Live, where celebs, politicians, and the rest of us could play and troll side-by-side. It meant chats, face-offs, and collaborations that wouldn’t have happened in the before times, when geography still meant something and stars were booked and busy. It meant engaging with the politics of race and class and inequity, in tandem with the protests that finally got us out of the house. And it meant leaning way into gallows humor, nonsense, and camp. With so many limits on our real lives, we were finally ready to move to the Uncanny Valley.

In that spirit, Vulture brings you the Quarries: our first, and hopefully last, ad hoc awards for the culture that came out of our year in quarantine. There have been thousands of livestreams, memes, virtual concerts, and other ephemera — this list represents the ones that most memorably shaped our locked-down lives (and brains). Some of it was absurd, some ingenious, some unintentionally amusing, some frankly reprehensible (and therefore unforgettable). And all of it kept us just on this side of sane, as we dragged our withered bodies through the longest nine months on record.

We were all so naïve. By the second week of March, at least in New York, we had one foot in the before-times and one big toe feeling out what would become the rest of the year. Before late-night and daytime shows went on a brief hiatus, and then adapted with at-home editions out of the studio, The View came up with a genius interim solution. On March 11, the talk show went ahead with an episode featuring the hosts around their signature table without a live studio audience, speaking to rows upon rows of empty folding chairs. Whoopi Goldberg addressed the dead space where an audience wasn’t, stretching out her arms and yelling, “Welcome to The View!” over and over, to zero people, while upbeat music played and the camera panned across a ghost town of empty chairs. (Cut to Joy Behar, reaching for the Purell on the table.) The episode is an eerie time capsule of how an entire genre of media that for decades has relied on the energy of in-studio audiences adjusted to a world where people could no longer gather. It’s the most Lynchian piece of media to come out of the pandemic — and this is a year that saw David Lynch himself release daily weather reports from quarantine. —Rebecca Alter

The first truly camp piece of quarantine art washed up on our digital shores like a bloated whale carcass on March 18. Motivated by an unknown force, Gal Gadot rounded up her celebrity friends to record an off-key rendition of John Lennon’s “Imagine.” Ostensibly as a way to cheer people up, the group sang a song whose lyrics implore everyone to imagine a boundaryless world where people “live as one” … in 12 different keys … with half of the participants wearing the facial expression of a disillusioned long-term hostage. Though the video, as Gadot put it, “didn’t transcend” in the way she intended, it did transcend as a gorgeous work of 2020 camp: an utter misreading of the public mood, a failure of both intention and execution that only served to illuminate the ways in which the pandemic was not actually affecting the lives of the rich and famous, save for imbuing them with a false sense of martyrdom. It is and remains insane and beautiful, a relic of a now-lost time when celebrities believed that singing a song together would be enough to save the world. —Rachel Handler

In the middle of a racial reckoning influencers tried to solve with black squares, comedian Ziwe Fumudoh donned elbow-length gloves, leaned so far into her phone camera that it felt like she was breaking social distancing, and challenged her guests to confront their racism, all with a smile. On Ziwe’s Instagram Live Show, “canceled” guests like influencer Caroline Calloway trip over such questions as “When you say Black people, do you capitalize the B in Black?” and seemingly easy ones like “Qualitatively, what do you like about Black people?” Ziwe’s straightforward inquisition gave us hilariously uncomfortable moments like Calloway proclaiming she’s the “only white person ever who read If Beale Street Could Talk before it became a movie.” The brilliance came from watching it live, cringing in real time. Ziwe kept summer interesting with this weekly crash and burn. —Zoë Haylock

Verzuz started out as a party and became must-see entertainment for our year inside thanks to a simple premise and a colorful cast of characters. Two performers get together to hash out which one has the better catalogue in 20 hits, bringing arguments that used to happen in schools, playgrounds, and hip-hop forums to life. As the series branches out, it has sought out legends and attempted to work out historical misunderstandings. The battles between Brandy and Monica and Gucci Mane and Jeezy addressed long-standing tensions; the night Gladys Knight and Patti LaBelle serenaded each other ranks among 2020’s best. Verzuz is, at its core, a simulation of the live experience, but occasionally it achieves something that couldn’t happen in a concert. In an arena, you couldn’t argue about who won in real time, or debate whether Monica was wearing waist-high boots or high heels covered by leather pants. (Solange created a Twitter poll, and pants won by a narrow margin.) —Craig Jenkins

Just after much of America began to shelter in place in March, Nintendo released Animal Crossing: New Horizons. The game is a somewhat straightforward continuation of a long-lasting series, where characters tend to customizable little towns (or islands, in this case) by doing chores, building furniture, and interacting with local animal villagers. Owing to its enhanced online playing features, and the uncanny timing of the release, the world of Animal Crossing became a meeting ground for casual and serious players who couldn’t see each other in person. The game’s cutesy, back-to-nature aesthetic might’ve drawn a lot of people to it as an escape, but it was the creativity of players that made it a 2020 phenomenon. Taking advantage of the customization options, people hosted graduations and comedy shows with others on their islands, re-created scenes from movies, and developed shareable fashion designs for characters. Even in isolation, we must always find new ways to show off. —Jackson McHenry

The quarantine diary became its own genre this year, and Almodóvar’s was the pinnacle of the form. As a filmmaker, he thrives in the confessional mode — his characters are always revealing great secrets and scandals to each other — but he has been protective of his own privacy over the years. However, as Spain entered lockdown, the director posted a series of journal entries that offered a candid view of his life and his career. (Translated versions appeared at Indiewire and Sight & Sound.) Filled with book and film recommendations alongside memories of actors and actresses he had met in his career, the entries were playful, moving, and colorful, not unlike an Almodóvar film. And, true to form, they were sometimes bitchy — as when he revealed how Madonna treated him and Antonio Banderas (and, most important, Banderas’s then-wife) like “simpletons” during a dinner party in the early 1990s while secretly filming scenes for her documentary Madonna: Truth or Dare. At a time when the world seemed united in anxiety and grief, the director’s lively journal provided good old-fashioned gossip. It also suggested Almodóvar has a great memoir in him. —Bilge Ebiri

Blonde, gorgeous, rich, famous: Almost nobody has a life like January Jones. Like many celebrities, she often poses on her Instagram in bathing suits and expensive fashion in soft L.A. lighting just to remind you of all those adjectives. But over the course of the pandemic, she also offered a glimpse into the simulacrum of a “normal” life she leads. She gardened in Grey Gardens–like attire, she exercised at home by Hula-Hooping, she watched Annie, and she decided to learn to tap dance. In her best video, she plays with dolls of her characters Betty Draper and X-Men’s Emma Frost while sitting inside a gorgeous walk-in closet. Unlike the many dispatches from celebrity homes this year, the ones from Jones show she is clearly aware of the absurdity of her life. But just how aware is she? The more you watch her, the harder it is to tell, which feels like her whole point. —JM

With apologies to Jimmy and Jimmy and James, comedian Conner O’Malley was the late-night host who best spoke to a terrifying moment. When productions went dark, businesses shut down, and the streets of New York were empty, O’Malley put on his best corny late-night-host suit, strapped a GoPro to his helmet, a selfie stick strapped to his chest, and hopped on his bike. He hollered into the void as he pedaled his way across midtown to an eerie-quiet Times Square, shouting incoherent harassments at the darkened marquees of The Daily Show and The Late Show With Stephen Colbert. O’Malley’s aggressively chipper playlist contrasted with a spooky-dire Manhattan, and his unnerving comedy drove home just how inadequate the usual late-night monologue format was at tackling the moment. —RA

The internet has yet to properly thank Johnniqua Charles, the woman behind “Lose Yo Job.” The viral video depicts Charles being detained by a security guard at a strip club in South Carolina “for nothing,” as she explains in the impromptu song she breaks into. “You about to lose yo job,” she repeats, asking the cameraperson to “get this dance.” After the video went viral, it was only a matter of time before it got remixed by DJ iMarkkeyz and DJ Suede the Remix God. iMarkkeyz had already found success with his Cardi B “Coronavirus” remix, and the duo would later create “Victory!” based on a prayer by Donald Trump’s impassioned spiritual adviser. Each video took the frenzy of the meme and matched its energy, but none hit the way “Lose Yo Job” did — it became a popular protest chant across the country. Like great protest anthems before it, it was hopeful and triumphant, even as cops like those involved in the deaths of Jacob Blake and Breonna Taylor kept their jobs. —ZH

In a year with very few purely goofy things, at least there was Quibi, the short-lived short-form premium video app that promised to revolutionize mobile entertainment. In the end, Quibi accomplished very little, but it did successfully become the butt of many months of jokes. The pinnacle of these is also the simplest: a recording of a phone playing an episode from the Quibi series 50 States of Fright, in which Rachel Brosnahan plays a woman being poisoned by her prosthetic arm made of solid gold. The joke is the episode itself, because it’s almost unimaginably ridiculous. But the joke is also the recording of a phone, because Quibi’s own software made it impossible to share anything from the app without physically recording it with another device. This video is a meta-commentary on Quibi — a hilarious horror episode, captured awkwardly with the background sound of viewers laughing in disbelief. —Kathryn VanArendonk

Quarantine nights are long and unnervingly quiet. When the Zoom calls end, the group chats quiet down, and your phone quits chirping, it’s just you, the dark, and memories of everything you miss. Taylor Swift’s Folklore, recorded entirely in our year of lockdown, is an album populated by the kinds of thoughts we try to keep to ourselves these days — the pining for someone you can’t see, the wondering if you peaked in life as a child. Loneliness was the great equalizer in 2020, and Folklore spoke profoundly to that. —CJ

Megan Stalter is the hardest-working mommy in quarantine comedy, and we are all her unruly children. Over long, increasingly surreal Instagram Live sessions, Stalter has chaperoned a virtual prom, hosted Disney World career orientation, hijacked a home-shopping-network broadcast to sell her skeleton art, taught a bungee-jumping class, and been the most judgmental busybody in the women’s church social group. With the cadence of an MLM leisurewear Facebook post and the coherence of a “Live Laugh Love” picture frame hung upside-down, Stalter’s IG Lives have become event viewing for her fans, infusing our boring, homebound nights with frenetic character comedy. The concentrated hits of her character work in her short videos often went viral, especially when she managed to marry her zany to the moment. Take one from November 8, in which she imagines the staffer who booked Four Seasons Total Landscaping for a Giuliani press conference. Stalter manages to deliver pitch-perfect parodies of social-media behaviors and archetypes that we didn’t even realize had become tropes in the pandemic: how Zoom calls disrupt our usual social rhythms, and how housebound vloggers try to “perform” togetherness when none of us have any of our shit together anymore. The more climb-up-the-walls crazy some of us feel in isolation, the more Stalter resonates. —RA

The reaction meme of the year was born during an impromptu Instagram Live reunion between Raven-Symoné and Kiely Williams, stars of the 2003 TV movie The Cheetah Girls. The conversation stirs up decades of drama, which proves to be an emotional task. A distraught Williams leaves the livestream, no closer to reconciliation. Raven-Symoné, clearly unbothered but amused, begins to chuckle, then guffaw, then fully cackle, all by herself, while thousands look on. Instant meme. Two days later, Instagram user @lil_rob_98 reuploaded the clip set to the Lacrimosa movement of Mozart’s “Requiem in D-Minor,” adding a dramatic, slightly sinister tone to the video. It was the meme that spanned our 2020 emotions, from exuberant to unhinged. —ZH

Since March, DJs — famous and not — have been livestreaming sets to their followers, filling a national desire to leave our bedrooms for a night out. No one did it like DJ D-Nice, whose late-March “Club Quarantine” set was one for the books: 100,000 IG users — including Drake, Rihanna, Michelle Obama, Oprah, Bernie Sanders, and Will Smith — watched him spin, chiming in with commentary and jokes. Where else could 100,000 pairs of eyes see Rihanna clown Kevin Durant (“Should I wear a mask to this live?” the mogul asked the NBA player, who had recently contracted COVID) or call out Drake’s thirst? The socially distanced set was a full VIP experience, mixing music with a messy comment section. —Hunter Harris

One thing we’ve learned from Sarah Ramos’s Twitter presence is that all of the young Hollywood actors seem to have each other’s phone numbers. Ramos, best known for Parenthood, spent her quarantine getting her friends to help re-create scenes from their favorite movies for the benefit of social media. She got Tavi Gevinson to do an exaggerated ScarJo in that big Marriage Story fight and harnessed Elle Fanning’s sweet blondeness as funhouse Cameron Diaz in My Best Friend’s Wedding. Her masterwork? Getting Dylan O’Brien to eyebrow-scream-moan as Andrew Garfield–as–Eduardo Saverin in a scene from The Social Network. Like many of these actors, he’s someone you might better know from franchise work. But with most of their work paused, it turns out they can be a lot more creative than the industry typically lets them be. —JM

We know. You’re sick of this guy, but listen: These were absurd. The powerpoint presentations Governor Cuomo used during his daily COVID-19 press conferences were informative, yes, but their bluntness distilled the horrors of our new normal into pithy rectangles. His wry catchphrases — “Today Is Saturday” ”COVID Is the Grinch,” “Now is not the time to fight for your right to party” — stood alone in a bold font on each slide, making them perfectly screen-capable and meme-friendly. Our retinas were so bombarded with constantly changing information — Wash your hands for 20 seconds; the virus actually came from Europe; children could be immune; it doesn’t really live on surfaces for that long — something comically simple was all that our brains could handle. The surreal humor of that fact made them an internet sensation. —Tara Abell

Hosting large studio audiences this year was out of the question, so American television producers got creative. In an attempt to maintain a semblance of normalcy, they did something profoundly and memorably weird by having virtual audiences stand in for the real thing. The only thing goofier than viewers dancing on live television is viewers being beamed into television while dancing in their living rooms via what looks to be a Zoom call. Or, if you’ve watched much pandemic-era daytime television, by placing vertical screens in the seats where a live audience would normally sit so that they resemble tombstones. Because this was done in sincerity, the humor was rooted in the disconnect between the intention and the result. Producers wanted us to feel like nothing is out of the ordinary; instead, it felt like waking up from a coma ten years in the future and seeing all the ways people use tech to pretend to be present for each other. —CJ

In the first two weeks of Drew Barrymore’s new nationally syndicated daytime talk show, she hosted a Charlie’s Angels reunion, staged a 50 First Dates reboot, interviewed an American Girl doll, and debuted a remarkably Dadaist segment called “Drew’s News.” “Drew’s News” is either a deconstructionist parody of human-interest local news stories or a genuine but failed attempt at an aggressively apolitical “Weekend Update.” The result is sprightly, hilarious, bizarre, failing at the polished and established rhythms and beats of daytime TV and achieving something all the more fascinating — like Barrymore’s now-canonical riff on “snake eggs,” which sounds like if a Charlotte York robot at a Sex and the City–themed Westworld got water poured into her mainframe and started to malfunction. The Drew Barrymore Show premiered during the pandemic, which would explain so much of its “off” feeling; instead of an in-studio audience, the video wall of smiling fans loom bizarrely and laugh a second too late to every joke. Despite these quarantine adjustments, or maybe because of them, Barrymore compensates with the energy of a thousand studio audiences. Long live daytime TV’s most intriguing new series. —RA

How did Fiona Apple know that we’d need this exact album at this exact time? Though Apple worked on Fetch the Bolt Cutters for years, each song on the record — which she pushed her label to let her release early — somehow speaks directly to the experience of self-isolation. Apple’s voice loops and howls as she sings about loneliness, feeling trapped, craving love, missed connections, depression, and emotional breakthroughs. But it’s the dozens of memes inspired by its title track, “Fetch the Bolt Cutters,” that will forever be associated with this time, when we needed new words for how to break free. —RH

Leslie Jordan had a solid career in TV comedy (including a 2006 Emmy for Will & Grace) before 2020, but in his Instagram videos, he unlocked a new level, and audience, for his work. Often filmed in extreme front-facing camera close-up and with repeated references to “Mama,” “Daddy,” and his “fellow hunker-downers,” the videos present characters that have the air of Tennessee Williams spinning out in front of his imaginary friends. Jordan, a fey gay man of the type who’s usually just a guest on TV, became the main character on Instagram. The result is something between character comedy and confessional, Jordan playing both himself and Blanche DuBois if she had a vlog — always lilting, always fascinating. —JM

When venues closed, and fans and artists struggled to find ways to replicate the live concert experience, no one did it better than our resident futurist Erykah Badu. The Texas singer’s Quarantine Concert Series charged a nominal fee for access to a live show from inside her home, where fans voted on a set list, and Badu and her band wrecked house, playing long and deconstructed versions of her best songs. Part of the loose, freewheeling spirit of Erykah’s Apocalypse hinges on the setting — her bedroom. It’s rare to see the legend literally let her hair down or vamp on old gospel tunes at a formal live gig. (You wouldn’t see that on anyone else’s stream, either. Badu’s sense of humor is unmatched — few livestream concerts were as playful.) That spirit of open adventure eventually seeped into the staging, which grew more elaborate as the series went on. By the third show, it looked like a dispatch from a moon colony. —CJ

With comedians stuck at home for weeks and months without live performances, the lip-sync surged to prominence in early 2020. Many of the biggest, noisiest versions were political — Sarah Cooper’s lip-sync videos of Trump, for instance, or Maria DeCotis’s Cuomo lip-syncs that turned his widely viewed daily briefings into fully enacted family dramas. Mary Neely’s are different. The form is mostly the same: Neely plays to a front-facing phone camera, mouthing along to someone else’s words in full costume. Like others, she uses elaborate editing to create full scenes with multiple characters using only her one-person production. Rather than lip-syncing along to news of the day, though, Neely takes on musicals. Her videos are feats of editing, involving makeshift costume and set design and a flair for caricature. In the best one, Neely performs a song from Beauty and the Beast that involves transforming into an entire village’s worth of chorus people as well as the protagonist. It’s charming, but it’s also full of a manic, off-kilter energy that felt like a key mood of the moment. —KVA

The shutdown put a lot of our best theater performers in a bind. Owing to various union rules, it can be easiest to perform in fundraisers and reunion readings, so actors often went back in roles they’d already performed. The 50-minute amfAR Angels in America video, though — a richly designed series of scenes from Tony Kushner’s masterwork — threw conventional casting to the winds. Here was your chance to see Brian Tyree Henry play Prior, a glimpse that opened up a universe of possible future interpretations; to see Glenn Close, her flintiness unlocked, play a dying Roy Cohn; to see 90-year-old Lois Smith play 30-something Harper, her warm wisdom making the alienated, pill-addicted, questioning Mormon’s speech “Night Flight to San Francisco” glow like amber. These were all-timer performances that pushed the stake further into the heart of all that cookie-cutter, one-to-one casting that has so often been theater’s default. Thoughtful, adventurous choices cracked open an era-defining play that’s been examined and reexamined, and it let us see our most precious stage treasures — all of them showing rich new colors in unfamiliar light. —Helen Shaw

In our physically withered spaces of quarantine, the hive mind wrote its own first draft of Donald Trump’s legacy in the form of hundreds of thousands of political memes. These single-frame visual protests, GIFs, and videos took over social media, overflowing with off-the-wall humor and outrage. Images of Trump sitting at a tiny desk, slowly walking down a ramp at West Point, and having a wee parade outside the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center while he was being treated for COVID became iconic within hours. Some of these fracas-filled messages are the greatest political ads ever made: accessible, direct, and propagandistically effective. They couldn’t stop the president from making the pandemic into a culture-war issue or from launching lawsuits against election officials. Together, though, they helped negate just enough of the continuous gush of bullshit Republicans pitched daily, providing whole minutes of relief. Visual shit-talking at its best. —Jerry Saltz

While millions around the globe weren’t traveling any further than their own backyards, a few boldfaced names were able to abscond to more tropical climes. Don’t worry; they took precautions. In September, The Walking Dead’s Daniel Newman tweeted a photo of himself and his friends cavorting shirtless in the sun, taking care to note: “private island all tested negative multiple times wear a mask” [sic]. The following month Kim Kardashian West posted her own holiday snapshots, explaining, “After 2 weeks of multiple health screens and asking everyone to quarantine, I surprised my closest inner circle with a trip to a private island where we could pretend things were normal just for a brief moment in time.” As an illustration of their authors’ warring impulses, self-promotion versus self-protection, these caveats were vivid prose; as an inoculation against judgment, they were spectacularly ineffective. While Newman and West technically weren’t breaking any rules, releasing luxurious vacation photos with thin disclaimers upon a locked-down populace was like wading through piranha-infested waters in Crocs. Each caption instantly became a meme, remixed with photos of Cast Away, The Wicker Man, Jersey Shore, and more. When you fail to read the room, the room reads you right back. —Nate Jones

Quarantine changed music videos, at least for a time. Production values eased up. Elaborate warehouse sets were out, candid videos were in. Tyga had a minor hit with what looked like FaceTime footage. Drake and Kehlani filmed in and around their homes. The most memorable tapestry from this year’s renaissance came from 645AR, a Bronx-born trap artist who started rapping in a high-pitched voice (think the “I’m sucking my own dick and dying” Vine from Nintendo’s Tomodachi Life) one day and quickly found himself collaborating with the likes of FKA twigs. His video for “Yoga” is a hyperreal, psychedelic dream sequence where he meets and befriends the coronavirus and they party in empty New York City streets, and … you just have to watch. —CJ

The idea of any one of these women performing “The Ladies Who Lunch” is up there on many Broadway fans’ vision boards alongside things like Mame dream castings (with probably a lot of Venn-diagram overlap). The “fabulous actress boozes at home” gimmick is an easy way to pander, but the scene works because all three so completely commit to the bit, pouring drinks for the benefit of the audience, like we’re all close friends. There have been thousands of live Zoom stagings this year, but these ladies managed to charge this one with a rare immediacy. It’s a scene that weaves together both the artificial intimacy of close-ups filmed at home and the kind of grandstanding only divas can deliver. —JM

Many episodes of TV came out this year that took on the coronavirus crisis. Between Zoom reunions, quarantine plots, and characters joking about masks, a lot of it quickly became tired. All except for Mythic Quest. So many special pandemic episodes this year were focused more on the crisis than on the characters, but Mythic Quest’s laser focus on just being a great episode of the series saved it from turning into a dreaded “special” episode. The relief of finding a special coronavirus TV episode structured and crafted like an episode of TV rather than like a celebrity phonathon would’ve been enough on its own, but it’s also remarkably moving, capturing both the absurdity and the gut-wrenching loneliness of life in isolation. Nothing since has lived up to it. —KVA

Like every episode of Wilson’s comedy docuseries How To, the finale, “How to Cook the Perfect Risotto,” works a bit like a personal essay. It’s Wilson’s thoughts on a theme, narrated by him and accompanied by scenes spliced from the documentary-style footage he constantly shoots of daily New York life. The show defamiliarizes all the things we take for granted, shifting our perspective so we can see the everyday for how strange it is. The finale is the best episode, and it begins with Wilson learning how to cook risotto for his beloved elderly landlady. It’s her favorite meal, and while she’s spent years cooking for him, he has never returned the favor. As Wilson proceeds with his project, the New York he’s been observing with a distanced, unflappable eye begins to change. The city suddenly goes into lockdown, and the familiar things Wilson has tried to register as strange become vastly more bizarre and unrecognizable. Wilson’s very small quest to make risotto takes on a massive scale when his landlady is hospitalized and he fears he waited too long to make it. The genius of the episode is in how unlabored it feels. It’s a testament to a truth of COVID-era art: Staring straight at the disaster makes it too difficult to fathom. The best, most moving COVID stories are the ones that come at it slantwise, embracing the frightening weirdness of this year rather than simply holding up a mirror to reality. —KVA

Everybody made art about feeling lonely this year, but Charli XCX made art out of the process of making art about loneliness. After pitching her fourth studio album, How I’m Feeling Now, in early spring, she publicly documented its making, using only the resources she had in her home as a self-imposed writing challenge. Over a month, the British pop star met with fans and collaborators in Zoom calls where she would provide progress updates and seek input on her songs. If you didn’t catch the Zoom calls, you could watch recaps of them on YouTube. The process flew in the face of music-industry convention, which calls for squirreling away material in secret and only showing it off when you have something polished to sell. The element of surprise is cool if a little overrated. How I’m Feeling Now is every bit as good as anything the singer might’ve made in a studio. If anything, seeing how the sausage got made helped fans feel even more connected to the project and to the artist, opening avenues of communication we sorely lack without live spaces to commune in. —CJ

Cooper’s Trump lip-sync videos, which launched just after most of the country went into lockdown this spring, are era-defining pieces of art. They combine several rising comedy trends and formal experiments from this moment: comedy played for a front-facing camera, lip-syncing along with popular songs and sound bites, and three years of Trump comedy that took aim at what seemed like an easy target and often struggled to land. Cooper’s lip syncs were vastly more effective in short, amateurish video form than they were when translated for her hourlong Netflix special; the up-close format of a social-media video is where her Trump is most at home. Her face becomes a window into his imagined inner life, bored but also groping desperately for his lines. Then she turns into Trump’s interlocutor, and her face is an exquisite, mute, often baffled plea. What does he mean? How can any of this possibly be real? — KVA

Leave it to the professionals. As the lip-sync has become a populist form over the past decade, maybe no one has done it better (on TV, that is) than contestants on the Olympics of drag, RuPaul’s Drag Race. When the pandemic forced the season-12 finale to go on Zoom, what could have been a dampener paradoxically produced one of the better finales in years, featuring a terrifically literal performance of Nelly Furtado’s “I’m Like a Bird,” by Crystal Methyd, and a living-room fantasy set to Ciara’s “Get Up,” by eventual winner Jaida Essence Hall. Constraint truly is the house mother of invention. —E. Alex Jung

Until someone shows me hard proof to the contrary, I will continue to believe that Mandy Patinkin and Kathryn Grody sprung fully formed from a field of sunflowers, singing show tunes and chomping on matzo. Mandy and Kathryn, who have been married for 40 years and have a dynamic that can only be described as “Jewish theater kid,” have spent most of their year in a bucolic country cabin alongside their son, who has been filming them. The videos, posted to Mandy’s Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok accounts, began in mid-April and traverse both style and content: spontaneous songwriting, impressions of dogs, a meditation on the concept of a GIF, an attempt to complete the lyrics of “Call Me Maybe,” and a Dali-esque meditation on the significance of voting. Together, they form a documentary series about partnership in isolation and perhaps the only successful marriage the world has ever produced — one defined by mutual respect, extreme patience, and the ability to laugh at one’s own mortality. —RH

Photo: JJ Darling

Patrick Foley and Michael Breslin’s Circle Jerk was that rare online performance that wouldn’t have been better in person. The duo’s farce about a Milo Yiannopoulos–esque supervillain felt born and bred to the digital environment, full of reenacted and montaged memes, as well as that hijacked-consciousness sensation that kicks in during your 15th straight hour on social media. That’s because the team invented a form of remote theater that had the energy of in-person theater (scrappy, costumey, full of frantic racing on- and offstage) and the mechanics of old live sitcoms, with cameras in position to capture multiple locations on a soundstage. The U.S. theater hasn’t figured out how to film and stream performances in a way that captures a sense of motion; best case scenario, in most Zoom theater, you might see part of the torso. But Circle Jerk wrangled a dozen programmable cameras and a truly dazzling video design to make a sharp, satiric, fully physical farce saturated in the intoxicating wine of the very online. It’s the first hybrid of its type, and certainly not the last. —HS

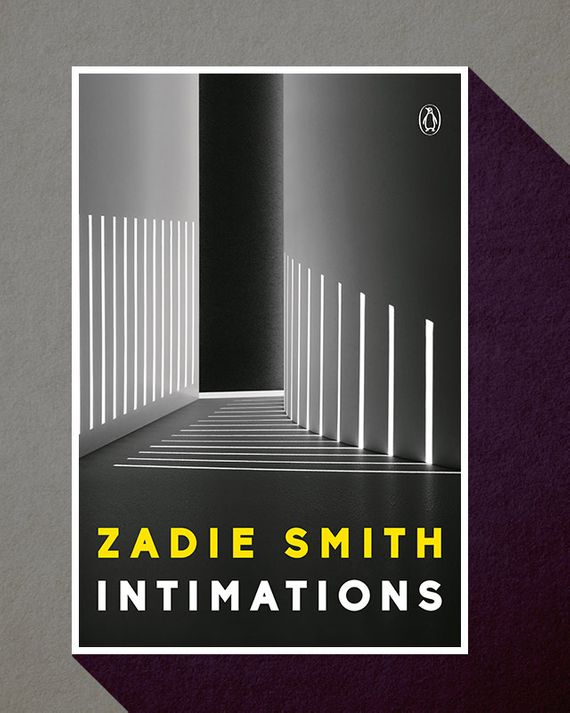

Publishing is one of those industries that remains stubbornly fixed in the middle of the last century. These people still do power lunch (well, they did, before COVID-19) and host “receptions” and often allow a year, sometimes two, to elapse between receiving a final manuscript and actually publishing it. If anyone was capable of disrupting this nostalgically paced workflow, it was Zadie Smith. Smith (and Penguin Books, her publisher) crashed a collection of essays in what must have been three or four months from start to finish: Intimations, a sharp little arrow of observations about life during the pandemic. It is about aging, brutality, peonies, George Floyd, Trump, and the nature of time itself. It is utterly specific to this moment in time and destined to be read for decades to come. —Molly Young

This summer’s political conventions served powerful cringe. Republicans gave time to the couple who waved guns at Black Lives Matter protesters in St. Louis. Democrats bored us to tears with sentimentality. The RNC’s most enduring moment was the deranged shriek of former Fox News contributor Kimberly Guilfoyle; the DNC’s came during the closing credits, when actor and singer Billy Porter and folk-rock legend Stephen Stills duetted on “For What It’s Worth,” a song Stills wrote in the wake of riots in the ’60s during his short stint in Buffalo Springfield. The point was to draw parallels between two similarly divisive moments in American history, but what actually happened was side-splitting comedy. Porter delivered relentless camp with a straight face and a long-flowing robe, overdoing the choreography and selling incredible vocal runs. If you’d been drifting off at the end of the evening, you weren’t anymore. Were they deliberately trying to razz us? A perfect 30 Rock parody of itself. —CJ

Watching this two-minute video of Sohla El-Waylly absolutely schooling her (mostly white) Bon Appétit colleagues on literally every culinary topic, one begins to wonder how anything got made in the Test Kitchen without her. Want to temper chocolate? Cook a starch? Make a giant tortilla? In this supercut of those moments — and in the many, many others cobbled together by fans online — you get a sense of just how much the other members of the Test Kitchen relied on her encyclopedic brain. It appeared online after El-Waylly said that, unlike some of her colleagues, she was not paid extra for her video appearances. The implosion at BA happened at a moment in time when the comfortably powerful suddenly found themselves unsteadied — a shift just consequential enough to force people to look at the whole enterprise differently. Suddenly, this video wasn’t just a fan-made supercut but the sort of primary source that could change an entire narrative. While some of the other BA staff spent quarantine watching their reputations tarnish, El-Waylly found that her star was finally, deservedly, able to rise. —Madison Malone Kircher

In July, BuzzFeed’s Tasty published a video called “These Are All Cakes,” featuring a realistic red Croc shoe, toilet paper, bananas, and more disguised cakes, all made by Turkish baker @redrosecake_tubageckil. Soon after, the internet was flooded with videos of everyday objects being sliced to reveal they were actually cake. Reality became questionable. Objects were stabbed simply to see if they were cake: full cans of Chef Boyardee, actual Crocs, tissue boxes. Some imagined the end of the coronavirus only leading to the dawn of cake. Ben Schwartz penned a Creepypasta-worthy tale of his mother turning into cake. You, too, could be cake. The cakes are impressive works of art on their own, but together, they became evidence of our shared mania. —ZH

Bad Bunny is special. This is apparent in the magnetic personality he radiates in photo shoots, interviews, music videos, and performances, and in the global charts, where he continues to make history as one of the most streamed artists on the planet. You could feel it in September as he cruised through Harlem, Washington Heights, and the Bronx (areas of New York City where his music rings out year round), performing on top of a moving bus, followed on foot and motorcycle by adoring fans. But nowhere was it more evident than in his impromptu Instagram Live stream this May, during which he celebrated the success of his sophomore solo album, YHLQMDLG, with a concert from home. Benito talked about life and music, twerked, and sang into a spoon for three hours, looking like a kid living out his pop-star dreams for an audience of a bedroom mirror. Somehow, Benito still beams star power even while curled up on the couch staring at his phone. The night felt as intimate as a FaceTime call with a friend, except over 300,000 friends tuned in, pushing past the IG Live record set by Drake’s Dark Lane Demo Tapes party two months prior. The greatest entertainers don’t need a stage. —CJ

Illustration: Ari Liloan

There are a half-dozen movies vying for the distinction of being the first feature shot during the pandemic, but the horror film Host has the advantage of (1) having actually come out (on the streaming service Shudder) and (2) being totally scary. Conceived during lockdown by director Rob Savage, Host is a scrappy, hourlong affair about a group of socially isolating friends who hold a Zoom seance as a lark to stave off boredom. Some take it seriously, while others are just looking for company while they get drunk. The semi-improvised naturalism of the virtual gathering makes it all the more startling when the ceremony goes wrong and spooky stuff starts to happen. Lights go out, chairs fly across the room, and feet dangle into the frame like they belong to a hanging corpse, only to vanish when the camera whips back around for another look. The DIY effects work improbably well, but what makes Host more than just a clever novelty is the way it leans into the limits of online communication. The participants in the seance may be close enough digitally to accidentally summon a demon together, but once they start getting killed, their individual isolation becomes everything. All they can do is stare helplessly at their screens as their friends are picked off, one by one. —Alison Willmore

The VMAs have a reputation for being one of entertainment’s wilder awards shows, and 2020 was no different. After initially hoping to host an in-person ceremony, MTV pivoted to an outdoor one spread across New York City. Sure, we made fun of the idea at the time (ferrying a performer out to Staten Island?), but it allowed for a show that reflected our tech-tethered year. The performances came from everywhere and nowhere at once: Maluma at the Skyline Drive-In, BTS in front of a green-screen Dumbo, Black Eyed Peas on a rooftop-meets-simulation, Chloe Bailey saying “VMAs” into the void. If such a show was made for anyone, it was Lady Gaga, whose stage was set as the fictional planet Chromatica (named for her album), and who performed wearing bionic, light-up face masks. It was just another day of being Gaga, and maybe the most normal nine minutes of pop this year. —Justin Curto

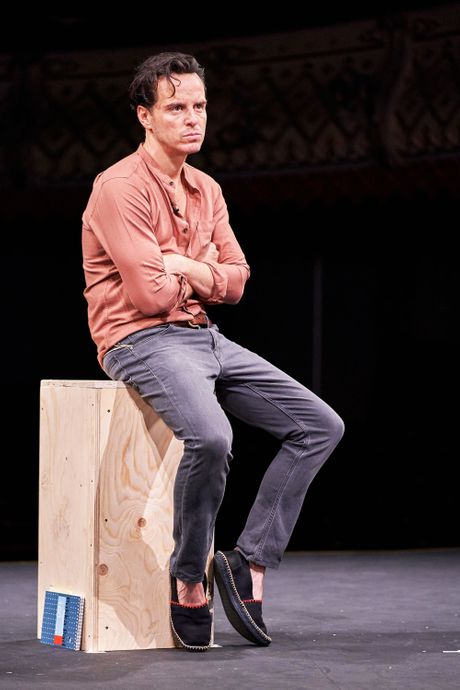

Photo: Manuel Harlan

A vacant theater is poignant. It’s a space filled up with ghosts, haunted the moment the audience files out. “How sad,” you say? How handy! It turns out that empty stalls are the perfect amplifying backdrop to any number of plays, particularly if you cast magnetic actors who can command all that echoing space. The Old Vic’s “In Camera” series is shot in its own desolate London auditorium, with socially distanced actors standing onstage while cameras shoot livestream video from multiple perspectives. All three of the “In Camera” offerings — Lungs (with Claire Foy and Matt Smith), Three Kings (with Andrew Scott), and Faith Healer (with Michael Sheen) — have been tremendous uses of talent and, yes, sorrow. While the few other theaters streaming stage performances try to hide their empty chairs, the Old Vic shows them, turning everything it broadcasts into a stark, Beckettian triumph. —HS

A lot of people compared the four-day time period between Election Night and when the race was called to tantric sex (because they’re sick freaks). Enter the Avengers. Well, more accurately, a heavily edited video of the Avengers with the faces of contemporary liberal political heroes pasted onto the characters’ heads, re-creating the iconic “Avengers assemble” scene from the climax of Avengers: Endgame: Biden was Captain America, Trump was Thanos, Barack Obama was Black Panther, Bernie Sanders was Dr. Strange, Kamala Harris was Falcon, Hunter Biden was a disheveled Thor, and on and on. It just … it just … it just was so stupid. And funny. And weirdly affecting. All over Twitter, people said it made them cry. But what kind of tears? Some saw it as a hilarious parody of naïve political memes. Others took it in earnestly and were moved accordingly. A third group both assumed it was earnest and thought it was funny. Eventually, Brooklyn filmmaker John H. Piette announced he had made it with pure intentions. That’s the internet for you — you can’t control how your work is perceived. Context-loss is one of the many reasons social media has become a hellscape, but occasionally it results in brilliance. —Jesse David Fox

An online, space-themed multiplayer video game akin to the high-school party-game classic Mafia, Among Us was released in 2018 but received a quarantine bump this summer when everyone discovered the joy of playing with (and murdering) your friends onscreen. But you didn’t have to take part to enjoy the game. Among Us became especially popular as a digital sporting event on Twitch streams, where viewers could watch players talk over video of themselves playing in real time — whether those players were a clique of online personalities, or Congresspeople AOC and Ilhan Omar, who played to get out the vote. Since the game puts you in a group chat whenever a player has accusations to make, it forces everyone into natural conversations, leading to an engaging drama of alliances and double crosses (and, inevitably, a flourishing collection of memes about Among Us dynamics). What better way to foster a real sense of togetherness than by ruthlessly accusing each other of being sus? —JM

Gal Gadot may have been the first to flail, but it’s been a rough year for stars all around, stuck as they are in a social-media panopticon. For the rest of us, celebrity gossip has provided a much-needed balm — the dumber, the better. Which is where @deuxmoi comes in. Since March, the private Instagram account has dropped daily dispatches on all manner of celebrity behavior. (Some name names, others are blind items.) Every report is user-submitted, and much of it is purposefully mundane: it might reveal Chris Evans’s sandwich order, say, or the speed at which Harry Styles runs on a treadmill. Occasionally, as when Taylor Swift’s former neighbor sent in a snapshot she’d taken through the singer’s window, the account verges on dystopian. The commentary can feel like a reflection of our Manichaean relationship with celebrities, whiplashing between unbridled standom and fierce condemnation. At its best, @deuxmoi acts as a counterpoint to this type of coverage, reveling in the truth that that stars—just like us—are mostly kind of boring. —NJ

While many of his peers spent the year sitting on their hands, waiting for quarantine to end — or for someone else to find them a lucrative pandemic hustle — Scott cut outrageous deals. (You can now buy a Travis Scott Chicken McNugget pillow.) But his master stroke was his Fortnite concert, attended by 12.3 million live viewers. Astronomical started with the Houston rapper hurtling toward Earth in a comet that landed in time with the drop from “Sicko Mode.” From there, a ten-story-tall, CGI Trav ran through a medley of hits, enveloping players in trippy, immersive underwater and outer-space themed visuals. It was an entertaining consolation prize for fans who miss sweat-drenched moshing to “Drugs You Should Try It” in arenas. As usual with Travis, he didn’t invent this practice so much as attach a notable pop-star face. But after Travis got onboard, Diplo, BTS, and J Balvin all made special content for Fortnite too. —CJ

Writing a play is a lonely process. Celine Song’s delightful mash-up of The Sims and Anton Chekhov’s 1895 Über-classic The Seagull turned the process into a joyful collective task, one that her watchers could weigh in on during the two-night Twitch-streamed event. Song’s online audience kibitzed as she chose clothes and gaits for the character’s avatars, delighted when they agreed on which perky swagger matched which gloomy Russian. This was catnip for theater dorks, who made jokes about “Chekhov’s gun” or “new forms” in the chat as fast as the other nerds could lol at them. It also resulted in a mass engagement with crucial Chekhovian questions. How do you drive a man to grief? Do the conditions exist for romance, in the absence of true friendship? All the giggling over Sims humor didn’t hide that Song was rewriting the artform itself, typing in the cheat code for a new kind of authorship. —HS

If the planet is still around in a thousand years and those who inhabit it seek to understand the time immediately preceding our global climate crisis, hopefully they can transfer the data to their iPhone 400s and gain access to our TikToks. It’s not because the other works of art created during this year aren’t worthy of study. But what other medium truly nailed the essence of 2020’s mania? No sanitized, COVID-bubble production set could capture the vibrating anxiety, unrelenting boredom, and contagious creativity that quarantine bred. All the messiness of 2020 — politics, the breakdown of social structures, our increasingly soft brains — converged on the app, and did a little dance. —ZH

*A version of this article appears in the December 7, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!