Quantum Operation Inc

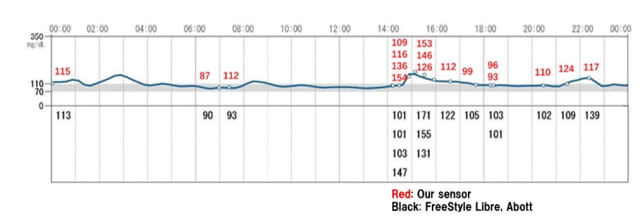

Quantum Operation supplied a sampling of its data compared to that made by a commercial finger-prick monitor, the FreeStyle Libre. And, at this point, there does seem to be a noticeable amount of variation between the wearable and the Libre. That, for now, may be a deal breaker for those who rely upon accurate blood glucose readings to determine their insulin dosage.

Noninvasive glucose monitoring is something of a holy grail for the medical industry, as well as the major wearables brands. After all, one in 10 Americans are diabetic, and that figure is likely to rise as the obesity crisis continues to rage. In order to maintain their health, diabetics today either need to take regular finger-prick blood tests or wear an implanted glucose monitor. In the last five years, companies like Dexcom and Abbott have even found ways to connect these monitors to smartwatches for ease of tracking.

Naturally, the wearables industry has been looking for an easier, and less invasive, way of doing this to try and steal some of that lunch. Unfortunately, no company has been able to successfully demonstrate a working version of this technology, at least not to a commercial standard. In 2017, one company — PKVitality — came to CES with a watch that had a series of 0.5mm tall needles on the back of its watch which collected interstitial fluid from your skin. But that hardly counts as noninvasive.

Apple has been reportedly working on a blood sugar monitoring platform since even before Steve Jobs died. Rumors surfaced in 2017 that the company had a dedicated lab looking at ways to monitor blood sugar through a wearable. In 2018, AppleInsider found a patent that the company had filed, related to using absorption spectroscopy to monitor blood glucose levels.

This secret team was apparently bolstered by the former employees of C8 MediSensors, a company which failed to achieve this task at the start of the last decade. It raised $60 million in investment from companies like GE, but failed to create a working product before it closed in early 2013. An MIT Tech Review profile of the company from 2014 said that C8 simply couldn’t fix the variability problem — where readings differ from person to person — before it ran out of money.

A technique called Raman Spectroscopy has seen some promise both in the above example and in other projects. In 2018, a group of researchers at the University of Missouri and MIT found that a laser, through a fiber optic cable, could be used to monitor for glucose when pressed against the wrist. At the time, researchers said that the system could offer readings comparable to a finger-prick test.

There’s still a long way to go before we’re able to see this sort of technology in a working product, even longer before it’s in one we want to buy. But if Quantum can demonstrate that it’s avoided the pitfalls that some of its rivals have hit, and that its technology is accurate enough, this could be pretty exciting.

Of course, this being an all-virtual CES, it’s even harder to take the company’s fantastic claims at face value. If we were at the show in person, we’d be able to test the device out for ourselves and speak to the founders face-to-face. It’s worth noting, too, that there isn’t — yet — any peer-reviewed or otherwise externally-validated science to support this specific technology and its application. We can’t make any serious judgment on this technology yet, beyond saying that if Quantum Operation can make good on its claims, then we may be on the cusp of a very exciting time for wearables.