Every so often, at one of the camps he runs for kids in his native Australia, Patty Mills will be approached by one of his lifelong fans with a request: Can you dunk for me?

For most NBA players, it’d be a breeze. He’d clear out a path, measure his steps and drive the ball through the rim with authority. He’d land, and his admirers would celebrate, because they’d just seen something unfathomably cool.

Unfathomable is the right word for it, too, because there is a problem with this scenario: Patty Mills doesn’t dunk. Of all the choices he could make with the ball, dunking, he says, isn’t even an afterthought. “I want to say it’s at the bottom of the list, but to be honest, it’s probably not even on the list,” Mills says. On being unable to show off for the kids: “That’s a little bit of a def lating moment when I’m like, ‘Oh, I don’t think I can get there right now, mate,’” Mills says. “‘But I’ll keep working on it.’”

Mills is one of a handful of players in a select club: those with successful NBA careers who, for one reason or another, have never jammed. Since the 1996–97 season (the earliest data is available from Basketball-Reference.com) 1,801 different players have combined for 210,842 regular-season dunks, and 1,259 out of 1,367 players (or 92%) who have played at least 1,000 minutes have dunked at least once.

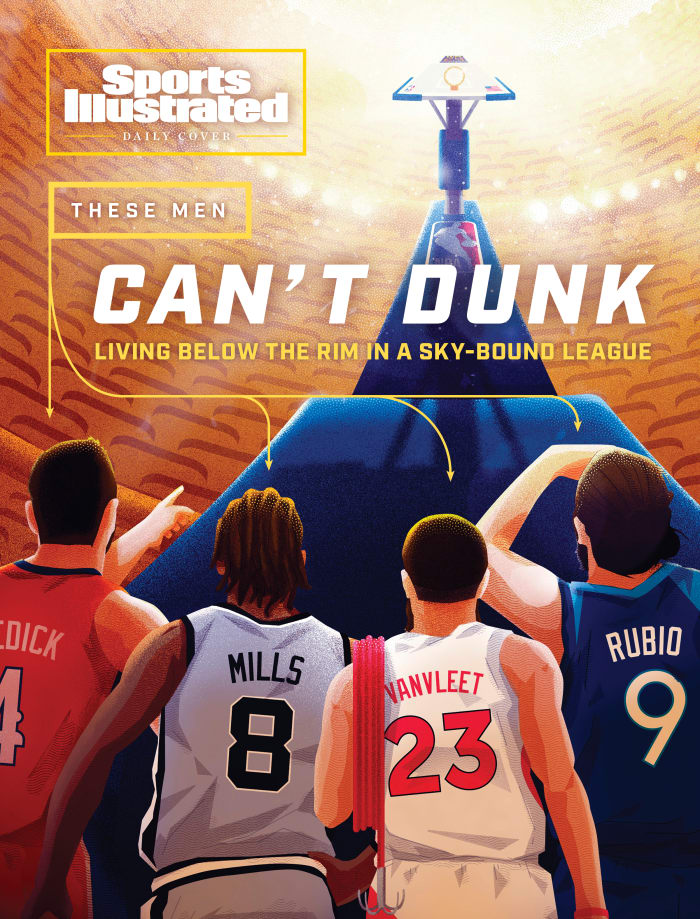

That leaves 108 consistent contributors across 25 seasons without so much as a delicate two-handed slam—11 of whom are playing this season. The list ranges from MVPs (Steve Nash) to solid veterans (JJ Redick, T.J. McConnell) to journeymen (Troy Daniels). Others, like Fred VanVleet, Ricky Rubio and D.J. Augustin, have played long enough to become league staples.Members of this earthbound club largely fall into two groups: the vertically challenged and the perimeter players told to stay out of the paint. The 6′ 1″ Mills, now in his 12th season, sits fourth on the leaderboard for most games played among active players without a dunk, is a member of both contingents and has resigned himself to a career without one.“It’s a massive part of the game and it’s what engages the fans and makes basketball basketball,” Mills says. “Putting a ball—slam-dunking it—through a hoop, I haven’t given that a try in a long time. I feel like the more I wait, the less of a chance that I have.”

Steve Novak wasn’t sure what to do when he got the call. It was early 2012, near the height of Linsanity in New York City, and his agent got word that the NBA wanted him to participate in the dunk contest. Jeremy Lin was sleeping on teammate Landry Fields’s couch at the time, and, as Novak remembers it, the plan was for Fields to dunk over a futon-bound Lin. When Fields had to with-draw because of injury, J.R. Smith was tapped to take over. When Smith pulled out because of a bum ankle, the offer went to the next player on the list.

The NBA was eager to capitalize on the excitement sur-rounding Linsanity, and adding Novak, who had never dunked in five seasons as a professional, was just another wrinkle to the theatrics. For a role player with a few mil-lion in career earnings, the cash incentive ($20,000 just for participating) wasn’t insignificant, and the potential spotlight could have done wonders for the Knicks forward. He had been lobbying the league to let him join the three-point shootout, but they preferred Kevin Durant. At 6′ 10″, no player as tall as Novak has appeared in as many games without dunking. And he wasn’t about to risk becoming a meme at All-Star weekend.

In theory, dunking is what separates those blessed by the Basketball Gods and us common folk tethered to the earth. The average person can take 10,000 jumpers each week and eventually develop a decent stroke. And all it takes to become a solid defender in your weekend run is a willingness to pay attention to your opponent and play hard. But most humans could try to raise their frames toward the rafters from now until the day they die and still never come close to dunking.

Novak is quick to set the record straight: He can dunk. Or at least he could at one point. There’s proof somewhere on the internet if you know where to look: snippets of flashier jams from college and routine slams from practice and in pregame. He even remembers his first in-game dunk. He was in the eighth grade, towering over his fellow tweens at a whopping 6′ 5″. After seeing Novak throw it down in practice, a coach approached him with an incentive. If the big friendly giant could dunk in a game, he’d be rewarded with a $20 gift card to a local ice cream shop. “If I didn’t have motivation before,” Novak remembers, “I’m like, ‘This has got to happen.’ “

The dunk was a one-handed affair off a steal on the fast break. In his words, it was vicious. What he couldn’t have known then was that it’d be one of his last.

Novak’s story is surprisingly common in a league that idolizes the slam. Mills, McConnell and Daniels are among the countless players with stories about dunking on lowered rims in driveways and in backyards growing up, mimicking the high-flyers they saw on television. Dunking was one of the things that made them fall in love with the game. It’s just never happened for them in the pros.

As is the case with Novak, video evidence of Mills dunk-ing exists, and not just from the early years of his career. Before a home game against the Cavaliers in March 2017, Mills caught an alley-oop that he delivered with one hand before exclaiming to TNT’s microphones, “Aw man, I should’ve saved it for the game!”

A quick YouTube search will show videos of McConnell winning the 76ers’ preseason dunk contest (a competition he says he was forced into) in 2016 and Daniels winning Play of the Game honors during a stint with the then D League’s Rio Grande Valley Vipers in 2014 for a two-handed slam off a cut. So why haven’t any of them been able to dunk in an NBA game?

For starters, nondunkers are on the floor to do other things. Like Novak, who made 43.0% of his three-point attempts, Mills (39.1%) and Daniels (39.5%) are sharp-shooters from beyond the arc, and McConnell—who averages eight assists per 36 minutes of play—has a penchant for nifty passes. The contributions they can make by spotting up or finding an open teammate out-weigh the allure of a highlight dunk.

Another answer is fear. Novak recalls two real chances to log his first NBA dunk. The first came early in his career with the Clippers, when he “came up with a flat tire” and resorted to a finger roll. The other occurred when he played for the Knicks against the Bucks and was alone on the fast break. He steeled himself and decided this was his moment.

“I just took a little too much time getting down to the rim, and Larry Sanders, who was on the Bucks at the time, was trailing me like a bat out of hell,” Novak says. “And it kind of spooked me, so I rushed it, and, instead of getting my steps right, I just sort of finger-rolled that one, too.”

The threat of getting embarrassed at the rim weighs on McConnell, now with the Pacers, as well. “Being 6′ 1″, there’s a lot of players that look like rim protectors to me,” McConnell says. “If I see anyone—no matter who it is—within striking distance, I’m not attempting a dunk.”

Beyond that, dunking introduces health risks. Daniels, who’s currently unsigned after seven seasons with as many teams, says that despite being 6′ 4″ and having decent jumping ability, the elevated chances of getting hurt on a dunk are what push him toward layups. If he were to land awkwardly and turn an ankle, his career could be put in jeopardy.

“I rarely dunk when I work out,” Daniels says. “It be-comes second nature to me to try to shoot a layup or a floater. Obviously guys are a lot bigger in the NBA—a lot stronger. Your chances of getting that dunk are slim-to-none, and your chance of getting hurt is very high. . . . I don’t want to try to do something that I’m not really familiar with and end up hurting myself.”

Long gone are the days when coaches would tell Novak that taking a three rather than fighting inside was “settling.” But Novak is an outlier even in this group: He not only never attempted a dunk in his 11-year career, he attempted only 16 layups. He was a stretch four before most stretch fours were used properly, and 78% of his career field goal attempts came from beyond the arc.

At first, coaches couldn’t unlock him. He was a towering forward who wasn’t much for banging in the paint and wasn’t likely to ever become a glass eater. It wasn’t until Rick Adelman was hired to lead the Rockets before Novak’s second season that things started to click. Later, when he played for Mike D’Antoni in New York, his skills as a shooter became a feature of the Knicks’ offense.

“He would say to me, ‘Hey, Steve, I know the guy you’re guarding might be able to score on you. I’m fine with that. I’m not O.K. if he scores more than you,’ ” Novak says. “And it’s like, Whoa. That makes so much sense to me. If I make three, and he makes two, we’re good out here.”

Just because some players choose to play below the rim doesn’t mean they don’t watch with wonder when teammates or opponents soar above it. McConnell remembers being awestruck watching his former 76ers teammates Richaun Holmes and Nerlens Noel throw it down in Philadelphia. Daniels cites Vince Carter and Derrick Jones Jr., who—despite having calves that Daniels says “look like [pencils]”—won the 2020 dunk contest, as his favorites. Mills has also played alongside plenty of high fliers, but he appreciates dunkers of every stripe. Late in Manu Ginóbili’s career, the Argentinian wing and a few Spurs teammates held a competition. Ginóbili, Boris Diaw and Tiago Splitter battled to see who would end each year with the most dunks. After hearing about the friendly wager, Mills made sure he was involved.

“I was never gonna get one, but I ended up being the referee and deciding what qualifies as a dunk for the other guys,” Mills says. “It was toward the end of all three of their careers. A dunk for them at any point was like a big dunk.”

Splitter, who stands 6′ 11″ and weighed 245 pounds during his career, won every year, but at various points during each season, Diaw and Ginóbili took the lead. The only sure thing was Mills and his goose egg. The countless layups were a far cry from his first dunk as a teenager, when he posterized an opponent so violently that he stood in shock while his cousin—a teammate—screamed and jumped around him. The moment felt rare, even then. Still, he doesn’t feel as if he’s missed out on anything, aside from maybe some street cred among his younger fans.

McConnell hasn’t completely counted out his chances of dunking before retirement, though he doesn’t seem to think it’s likely. He prefers being on the other side of an alley-oop pass. “Maybe once before my career’s over, if I get a fast break, maybe I’ll get Myles [Turner] to lift me up and dunk. You know, when I’m like 33 or 34,” McConnell says. “It would have to be no one crosses half court and no-effort-from-the-other-team-type deal where I could possibly do something.”

As for Novak, he doesn’t regret finishing his career without a dunk, or turning down the invitation to the dunk contest. He still watches every year and laughs at the thought that he was once asked to participate. “I think, Holy, I made the right decision,” Novak says. “I would have had to somehow figure out a way to get the nine-foot hoop and a mini couch.”