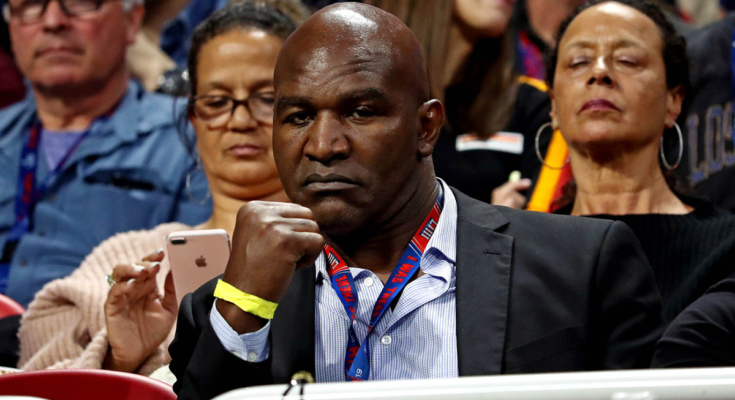

It was, in many ways, a familiar sight. Evander Holyfield, still sturdy, still chiseled, crouched in the middle of a boxing ring, a trainer holding mitts in front of him, an oversized fight poster bearing his likeness hanging behind him. Decades earlier, it would have been cause for excitement. Today, it’s outrageous.

Holyfield is 58. On Saturday, he will end a 10-year layoff when he faces ex-UFC star Vítor Belfort. He’s fighting because Triller, the music video app burning through cash in an attempt to gain a foothold in boxing over the last year, with Brewster-like spending, tabbed him to replace Oscar De La Hoya. The Golden Boy bowed out of the match with Belfort after contracting COVID-19. He’s fighting because Florida did what California wouldn’t: licensed Holyfield to fight in a fully regulated pro boxing match.

Holyfield is 58. Am I getting repetitive? Maybe because Holyfield is fifty freaking eight. A 58-year-old shouldn’t be boxing. He should be commentating. Or training. Or promoting. He should be an ambassador for the sport. Not participating in it. Belfort is 44 with limited boxing experience. But he’s heavy handed—at least he was in mixed martial arts—with something to prove. A win elevates him back into a fight with De La Hoya. A loss ends his career.

This isn’t boxing.

It’s human cockfighting.

It’s Russian roulette with gloves.

Remarkably, Holyfield-Belfort has competition for the weekend’s most obscene event. Some 2,200 miles away, in Tucson, Ariz., Óscar Valdez, a 130-pound champion, will defend his title against Robson Conceição. This comes a week after Valdez popped positive for phentermine, a banned substance often used for weight loss.

After a hearing, the Pascua Yaqui Tribe Athletic Commission, which has jurisdiction over Valdez-Conceição, elected to allow the fight to move forward.

The WBC, which could have stripped Valdez of his title, chose to let him keep it.

Disgraceful. Is there any sport where performance enhancers are more dangerous than boxing? Valdez may have ingested phentermine accidentally. He has suggested the drug could have been an ingredient in an herbal tea (though he has declined to name any of the herbal teas he has ingested) or contaminated vitamins (though he has yet to offer up a list of vitamins that could have been contaminated). In an interview with ESPN, Valdez said “I’m still not 100% how [phentermine] got into my body.”

Whatever. Valdez’s part in this story ended when he tested positive. What he did was bad. What the tribal commission and the WBC did might be worse. The commission has offered no public explanation for why Valdez is being allowed to fight. The commission is not beholden to VADA, the Voluntary Anti-Doping Agency, which busted Valdez. But in 2018, VADA detected clenbuterol, a banned substance, in Canelo Álvarez in the months before Álvarez’s anticipated showdown with Gennadiy Golovkin. The Nevada commission suspended Álvarez for six months. Later that year, VADA popped Billy Joe Saunders, then a super middleweight champion, for oxilofrine before Saunders’s title defense against Demetrius Andrade. The Massachusetts commission denied Saunders a boxing license. The WBO stripped Saunders of his title.

There are precedents for incidents like this.

The tribal commission has chosen to ignore them.

Then there’s the WBC, which has long touted itself as an industry leader in drug testing. Valdez tested positive as part of the WBC’s Clean Boxing Program. It’s a program that works directly with VADA. Yet when VADA busted Valdez, the WBC chose to do … nothing. WBC declared phentermine “does not give any competitive advantage,” a statement widely discredited by experts, including Victor Conte, the ex-BALCO founder who, in an interview with Fight Hype, called phentermine “a potent, powerful stimulant … that makes you stronger, makes you faster [and] increases your training time to exhaustion.”

In a smarmy, condescending statement, WBC president Mauricio Sulaiman, who in 2018 stripped David Benavidez of his super middleweight title after Benavidez tested positive for cocaine, cited Valdez’s image as a “hardworking, clean, dedicated young man with an impeccable record” among the reasons the Mexican-born fighter will get to keep the Mexico-based organization’s title.

Much of the boxing world is unhappy Valdez (white trunks) is being allowed to fight.

Jim Krajewski/RGJ/USA TODAY Sports

“It is a real shame that there are those who do not have the slightest intention of studying and understanding what happened,” Sulaiman said. “They are not interested in seeing that it was a transparent and consistent process to the regulation, and they only choose to have their own opinion, their own conclusion, and thus express it publicly, hurting the image of a young person, as well as the integrity of the sport and the WBC.”

Right.

Good thing Valdez didn’t test positive for cocaine.

This isn’t media-manufactured, either. Fighters are weighing in. Caleb Plant, a 168-pound titleholder, tweeted “some people want to be great so bad that they cheat and then there are people who want to be GREAT so bad that they DON’T. Doing that isn’t confidence. It’s FEAR!” Shakur Stevenson, a stablemate of Valdez with Top Rank, said Valdez shouldn’t be fighting. Tim Bradley, an ESPN broadcaster, said he hopes Valdez gets knocked out.

The only people defending Valdez are those who stand to profit off him.

Just when you think boxing can’t sink lower, the sport finds a new shovel. There’s so much we could be talking about. Inspired matchups between great fighters, like Demetrius Andrade-Jermall Charlo, Ryan Garcia-Gervonta Davis or Errol Spence-Terence Crawford. Instead, a 58-year-old man with a battered brain will take head shots and a fighter weeks removed from a positive drug test will defend his title.

At its best, boxing is an incredibly compelling sport.

At its worst it’s … this.

More Boxing Coverage:

• Manny Pacquiao and the Fight for the Philippine Presidency

• Boxing Isn’t Dead. It’s Being Suffocated

• Don’t Count on Oscar De La Hoya and Other Legends’ Comebacks to Save Boxing