A guy walks into a bar. The guy is Peter Colton and the bar is called The Fours and he walks in every morning at 8:30, when the place looks more like a church. Amber light plays across dark wood and stained glass.

Jewel-toned bottles of spirits, in emerald and sapphire, are boxed up and waiting to be returned to their maker. Silverware has been scrubbed, sorted and laid to rest in slotted trays. All the tap handles stand upright, having taken their final bows.

On the walls are ghosts, as in the rafters of the old Boston Garden, which once stood a few hundred paces across Causeway Street, where the TD Garden is now. The Havana-born Red Sox pitcher Luis Tiant’s framed jersey from 1979 practically comes to life on a wall opposite the bar, like the framed portraits at Hogwarts. “Tiant was in here a couple years ago,” says Colton, 65, the hands-on owner of The Fours. “He taught us the proper way to make a Cuban sandwich.”

Doug Flutie’s signed Boston College jersey, hanging near the front door, was personally delivered by Flutie’s favorite B.C. receiver, Gerard Phelan, who retrieved it from the trunk of his car. And while many restaurants wouldn’t touch it with a 10-foot pole, The Fours mounted on a dining room wall the filthy 10-foot pole that was used to measure the regulation height of the rims for Celtics games at the old Garden. It would easily be mistaken for an oversize shillelagh if not for the brass nameplate The Fours had engraved for the display, as if this were the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and not, as SI declared it in 2005, America’s best sports bar.

Just as the Gardner had its famous art heist in 1990, when thieves made off with masterworks by Rembrandt and Degas, The Fours was robbed by window-smashing gunmen who stole game-worn garments signed by the Celtics and Bruins. Police never recovered the pilfered Parish, nor the boosted Bourque, but both players donated replacement jerseys, for it was a pleasure to hang in The Fours when they couldn’t hang out there.

No longer. After 44 years, during which 80% of its business came from the Celtics and Bruins games and concerts across the street, the Fours Bar & Grille permanently closed its doors to the public on Aug. 31. Colton continues to come in most weekdays, sometimes as the only passenger in the car on his commuter train. North Station is bereft of pedestrians at mid-morning. “We made it through all the walkouts and lockouts, the whole year [2004–05] hockey didn’t play, we survived the Big Dig, when it looked like Berlin at the end of World War II down here,” says Colton of Boston’s two-decade, $24 billion tunnel-drilling project. But the coronavirus pandemic has proved too much for too many.

In Boston alone, McGreevy’s, a baseball bar owned by the Celtic punk band Dropkick Murphys, has closed for good during COVID-19, as has Lir, home of the Boston Gooners, the local Arsenal supporters club. Both were Irish bar stops on the walk to Fenway, alcoholic stations of the cross for anyone matriculating down Boylston Street. A replica of the bar from Cheers closed in Faneuil Hall. “Running a bar is not like the TV show,” says Colton. With two floors of 3,500 square feet each, and a fire-code capacity of 395, he didn’t know everybody’s name at The Fours, though familiar faces still stop him on the red-brick sidewalk when he steps outside to draw a deep, distanced breath. Two former patrons recently broke down in tears encountering him on Canal Street. “You’re making me cry,” Colton told them.

“People tell me, We need this place. Without The Fours on this street there’s nothing here. I’ve been going here forever,” says Colton. “And they just expected it would be here forever and ever. But I could see it slowly slipping away.”

It slipped away in the night, like a thief with a jersey, without so much as a final farewell. A laminated statement was taped to the front door and posted to social media, and The Fours was mourned the way loved ones have been in the pandemic: on the screen of a smartphone. Celtics vice president of basketball operations Mike Zarren, on learning the news, estimated that a member of his family had been to The Fours after every C’s home game but eight since 2001. “Every basketball writer, C’s and B’s staffer, Boston sports fan, and out of town fan who stopped in was better off because The Fours was there,” he tweeted from the NBA bubble in Orlando. “This sucks.”

This is happening all over the country, of course, to all manner of businesses. Nearly 100,000 and counting have permanently shuttered since March 1, according to a Yelp report released in September, a number that includes thousands of restaurants and bars for whom it is closing time. Except the house lights are not going up, they’re going out, forever.

Near Wrigley Field in Chicago, Guthrie’s Tavern has shut down, and a half mile south, so has Southport Lanes, the bar and bowling and billiard hall that was there for 98 years. Lucky’s Pub, between the Dynamo’s stadium and the Astros’ ballpark in Houston, closed its doors and doused the largest HDTV screen in the city. Christie’s Sports Bar & Grill in Dallas, after 29 years, lowered cocktail umbrellas to half-staff. Lagasse’s Stadium, celebrity chef Emeril Lagasse’s sports bar in Las Vegas—it replaced Jay-Z’s sports-themed 40/40 Club there—has ceased to be. Capitol Lounge, the sports bar in Capitol Hill, closed after 26 years in which it steered by two stars: no politics and no Miller Lite. Bleachers in Redding, Calif., announced its own demise on Facebook: “Thanks to the coronavirus,” the owners posted, “time has come to say goodbye to our hopes & dreams.”

The nationwide lockdown arrived in March, the best time for sports bars, when March Madness, St. Patrick’s Day, MLB’s Opening Day and—for The Fours, at least—college hockey pay the freight for the leaner summer months of the NBA and NHL offseasons. As a result, perishable inventories were high when the bars shut down.

Even before COVID-19, as flex schedules and work-from-home killed the business lunch, and smartphones proliferated, communal experience was drying up. The first thing patrons do upon entering is slap a phone on the bar, just as cowboys did their guns in Western saloons. “Families come out to dinner and everyone has their phone out and no one’s talking,” says Colton. “It changed. It’s strange.”

Before every pocket concealed a camera, Celtics greats Larry Bird, Kevin McHale and Bill Walton would come in and sit at the bar like a living diorama. “They’d bust each other’s chops,” Colton says. (The 1979 press release announcing Bird’s signing with the Celtics, typewritten on yellowing letterhead, is framed above the bar.) These athletes used to literally give The Fours the shirts off their backs, but those shirts have become too valuable now and go to wealthy collectors or to charity auctions. “Guys used to say, ‘I’d love to have my shirt up there,’” says Colton. “Nowadays, it’s a different era.”

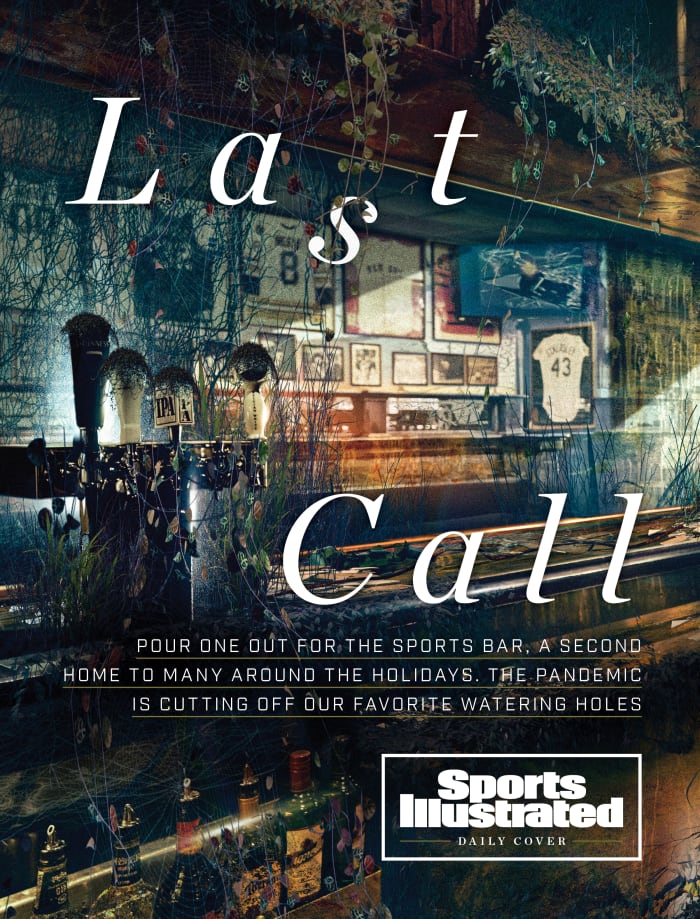

Located across the street from Boston’s arena, The Fours was a home to a trove of memorabilia.

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

Colton is standing at the host stand, like a priest in his pulpit, preparing to deliver a eulogy. Dust motes float in the half-light slanting through the louvered front window. Beneath the bar, snow-white chef’s jackets, starched and stacked—logo embroidered on the left breast—lie fallow. He surveys the treasures in The Fours, which include artifacts of random fandom: Joe Frazier’s silk robe, a 1948 Olympic rowing scull, Colton’s own mother-in-law’s cheerleading megaphone from B.M.C. Durfee High in Fall River, Mass. “I have to talk to our attorney today about liquidation,” Colton says, through a surgical mask. “I didn’t foresee this in my wildest dreams.”

***

Three thousand miles away, in San Leandro, Calif., Dr. Bob Gingery watches the slow fade-out of his favorite bar, Ricky’s, a Star Wars cantina for Bay Area sports fans and home away from home for the Black Hole, the cosplaying hardcore of Raider Nation. At Ricky’s, the pasta in cream sauce is called Fettucine Al Davis, in honor of the Raiders’ founder. A can of Ken Stabler’s Sugar-Free Snake Venom is preserved under glass like King Tut’s death mask. For these reasons, and many others, “It was almost more fun to watch a playoff game at Ricky’s,” says Gingery, “than to go to the [Oakland] Coliseum to see the Raiders play in person.”

Doc, as he’s known around Ricky’s, is only 5′ 6″, but for several years running he won the three-point contest at the Warriors’ fantasy camp, where Gingery first came to know then Golden State coach Don Nelson. Whenever the two men encountered each other at Ricky’s, a mile from Gingery’s office, Nellie and Doc basked together in the blue light of the bar’s ridiculous collection of TVs. There were more than 90 at last count, so many that an unpaid staffer named Maury happily worked changing channels for patrons, a job that required the diplomacy and dexterity of a U.N. peacekeeping force. Maury could switch a 60-inch screen from Stanford basketball to Sharks hockey from 30 paces away, anticipating the needs of the baying throng before the throng knew what it needed.

In those unfortunate intervals when Doc couldn’t make it to Ricky’s—when he was preoccupied performing life-saving operations as a vascular surgeon—Nellie would summon Ricky Ricardo Jr., whose family opened the joint in 1946 and moved it to its current location, on Hesperian Boulevard, in 1960, when the Raiders arrived.

“Call Doc,” Nellie would tell Ricardo. “Get him down here to eat one of these bad f—— steaks with me.” On those nights Doc and Nellie would repair to a small back room, where the diminutive doctor watched the 6′ 6″ coach smoke cigars with a dog at his feet, two things that were once simultaneously legal in gin joints across the country. “It’s such an iconic place,” says Gingery, who is 74 and a 25-year patron of Ricky’s. “It breaks my heart to think it won’t be there anymore.”

Ricky’s was there on Jan. 25, 1981, when the Raiders won Super Bowl XV, flew back from New Orleans and went straight from the plane to their favorite bar to watch the game on VHS. Ricky’s was there through the Raiders’ 13-year exile in Los Angeles, during which time Ricardo and his patrons continued to call them the Oakland Raiders, a practice that goes on to this day, after the Raiders have absconded yet again, to Las Vegas.

Whether Ricky’s will be there in 2021, however, is an open question. Ricky Ricardo Jr. died in November at age 75 after years of coping with Alzheimer’s. “His kindness will be missed throughout the East Bay and beyond,” the Raiders said in a statement. Ricky’s wife and business partner, Tina, has persevered through a Biblical year. In 2005, SI named Ricky’s the second-best sports bar in the nation, behind The Fours. But COVID-19—indifferent to rent and taxes—is almost insurmountable, turning that ranking of America’s best bars into an endangered species list.

And so Doc Gingery started a Go Fund Me for Ricky’s that has reached nearly $20,000, though the bar will need at least $50,000 to make it through the pandemic. Gingery has tried and failed to attract the attention of the Raiders, A’s and Warriors, and has instead collected cash from “little guys” kicking in $20 here and there, a ragtag and motley effort that is somehow in keeping with the spirit of Ricky’s.

“The socializing is what makes Ricky’s great,” says Doc, who loves the demographic mix of race and gender and occupation within. “If you start talking basketball to the guy next to you, you know it’s someone who knows what they’re talking about because they’re in Ricky’s. I met so many people in there.” He catches himself, in those last two sentences, slipping from the present tense to the past. The remains of three Raiders fans are interred outside Ricky’s, including one gentleman whose ashes were brought in by family in an ice cream bucket. “Who’s your friend?” Tina asked. They are all reminders, if any were needed, that dust we are and to dust we shall return.

“It’s just tragic,” says Doc, that these bars, with their ghosts, are becoming ghosts themselves.

***

The most enduring ghost bar in America is Toots Shor’s, the New York City watering hole once frequented by Yogi Berra and Joe DiMaggio. At Shor’s, Frank Sinatra and Babe Ruth might gather—together—at the circular bar. Ruth’s biographer Bob Considine kept an office there from which he filed columns, since every male star in the sports and showbiz firmament—Jackie Gleason and Jack Dempsey, Bob Hope and Bing Crosby, Casey Stengel and Willie Shoemaker—came to Shor’s, whose dyspeptic proprietor, an erstwhile bouncer named Bernard (Toots) Shor, addressed most of his patrons as “crumb-bum.”

Shor’s has only grown in legend since it closed in 1971, beset by tax liens, and is still remembered as “the most famous sporting saloon this country has ever known,” as this publication described it in a 1959 cover story. An Irish immigrant named John Clancy was assigned to serve the baseball legends there, precisely because he didn’t know who they were, and thus wouldn’t bend their ears about that day’s game. Shor’s is where the author of For Whom the Bell Tolls was introduced to Yogi Berra as “the writer Ernest Hemingway.” To which Yogi reportedly replied, “What paper you with, Ernie?”

John Clancy’s son Shaun followed his father to New York in 1991, fell in love with baseball and opened his own baseball-themed Irish bar in 2004, called Foley’s. The joint was named for Red Foley, a sportswriter at the New York Daily News and official scorer in 10 World Series. And so Foley’s became a 21st-century avatar of an old-time New York joint, recalling a time when baseball bewitched the boroughs and sportswriters were held in high esteem. Naturally, Foley’s was located on that most evocative of thoroughfares, Toity-toid Street, across from the Empire State Building in Manhattan.

It quickly became the bar of choice for out-of-town baseball teams and other members of the MLB circus: umpires, traveling secretaries, broadcasters, beat writers, clubhouse attendants, general managers, assistants to the general manager and scouts, so many scouts, among them the legendary Tom (T-Bone) Giordano. On his death at age 93 in 2019, he bequeathed to Shaun Clancy a beloved baseball, cubed in Lucite, and signed on the sweet spot by Pope John Paul II.

Giordano had worked with the Italian national baseball team, and it was in that role that he met the Pontiff 40 years ago. “When T-Bone found out he was gonna have an audience with the pope, he told the Orioles to send him some stuff,” says Clancy, who is 50. “So the Orioles FedExed—or UPSed, I dunno—a bag of stuff to him for the audience, this private audience, just him and the pope.” When the fraught moment arrived, as Clancy tells it, “T-Bone kisses the pope’s ring on behalf of [team owner] Edward Bennett Williams and the Baltimore Orioles. And as he pulls out an Orioles ski cap—before he got shot, the pope used to ski—T-Bone notices on the back of the ski cap it says: Maxwell House. That’s when he realized the Orioles sent him whatever free stuff they had lying around.”

The pope was in good company at Foley’s, where nearly 4,000 baseballs were on display, bearing the signatures of ballplayers (Aaron to Zimmerman), singers (Bono and Katy Perry) and other rock stars (including Dr. Frank Jobe, the Elvis of the elbow, who gave the world Tommy John surgery).

It wasn’t just this mix of stars and scribes that made Foley’s echo Shor’s. Both joints revered the lavatorial arts. “The most important person in Toots Shor’s was the guy in the bathroom, the men’s room attendant,” says Clancy. “He had the connection to tickets. So you’d go in there and say, I need two for the Yankee game, two tickets to the fight and two to Hello, Dolly!” This was the oil that allowed the engine of New York nightlife to roar.

In this spirit, Clancy tried to buy the toilet in the home manager’s office at Nationals Park in Washington that Pope Benedict XVI had at his private disposal when His Holiness said Mass there on April 17, 2008. The Nats, who had given the pope their skipper’s digs to use as his dressing room, declined Clancy’s offer, which included a promise to use that toilet for display purposes only. “I’d have mounted it on the wall at Foley’s,” he says wistfully. “The papal pooper.”

Like any venerable ballpark, Foley’s had a few ground rules. “A woman could sit at the bar and watch a game and have a beer and not be harassed,” Clancy says. “If you were looking to get laid, there were plenty of places to do that. Any woman who came to Foley’s was not looking for that.” Likewise, Foley’s staff would not abide any mention of politics, religion or weather. “If you have nothing better to talk about than weather,” Clancy insisted, “go somewhere else.”

Sports in general and baseball in particular were the primary topics of conversation, though patrons were forbidden to approach athletes and other dignitaries at their tables. This came to be known as the Jon Hamm Rule, in honor of the Mad Men star and St. Louis Cardinals fan “who would literally turn every woman in the room to mush,” says Clancy, who is perhaps not using literally literally.

But even that rule had a subsidiary rule, a loophole of sorts. “Here’s the rule,” Clancy told patrons, whether he was referring to Hamm or Yankees GM Brian Cashman. “You don’t bother him at the table. But at some point, he’s gotta pee, and you can get him going into or coming out of the bathroom. Just not in the bathroom.”

And so the five feet between the table and the can became a mixed zone for ballplayers and their public. “When I get to pee,” Mets captain David Wright once told Clancy, “Yankee fans are busting my balls or Mets fans are telling me to adjust my stance.”

Through months of lockdown, Clancy continued to pay his staff. But rent and taxes took their tolls and Foley’s closed for good Memorial Day weekend. “As it goes, it takes a significant chunk of the city’s heart,” wrote New York Post columnist Mike Vaccaro, the latest in the city’s long line of saloon-loving scribes.

Locking up the joint for the last time, dousing the lights, Clancy heard history’s most famous saloon singer in his head, the one who stiffed waiters at Toots Shor’s then handed a crisp $100 bill to the guy who hailed his cab. “Regrets, I’ve had a few, but then again, too few to mention,” says Clancy. “What made Foley’s Foley’s—the people—will return. We’ll meet again, don’t know where, don’t know when. Now I sound like another song.”

He’s a human jukebox, full of closing-time standards. But don’t play “Taps” for his taps. Not yet, anyway. “Foley’s isn’t dead,” says Clancy. “It’s not a brick-and-mortar site. It’s the people, whether the GM of a team or a guy who drives a bus for the MTA.” He knows this year has upset the cosmic order of things. A bartender pouring out his own sad story to patrons is unnatural. For now, though, another Sinatra song springs to mind.

It’s quarter to three/There’s no one in the place/Except you and me.

Set ’em up, Joe/I’ve got a little story/I think you should know

We’re drinking my friend/To the end/Of a brief episode

Make it one for my baby . . .

And one more for the road. Clancy sold his house in New York City to pay his bills at Foley’s and has decamped for now to Dunedin, Fla. “I’m riding out this pandemic,” he says by phone from the greater Grapefruit League, “getting over a sinus infection and when I do, I’m gonna walk across the street to Publix and get a job bagging groceries. How ya doin’? Where ya from?” He needs to be around people, physically connected, speaking unmediated by Zoom or FaceTime. “Foley’s will rise from the ashes,” he says, perhaps inside a ballpark, where he can dispense beer and watch baseball and share the company of 40,000 people.

Until then, Foley’s, like The Fours and Ricky’s and a few others, will survive as Shor’s did in the fuzzy memory of its patrons. For these few bars, posterity has conveyed a kind of immortality. They’re like the fictional pub in the Dylan Thomas play Under Milk Wood. It was called the Sailor’s Arms, where the clock hands were stopped at half past 11 in the morning, so that it was always opening time and the minutes, never mind the years, were not allowed to pass.