In the space of 35 days last winter, Isaiah Thomas was traded by a team that didn’t need him, released by a team that didn’t want him and then, like the rest of the NBA and the world, nudged into involuntary hibernation.

Suddenly there were no games to prepare for, no practices to attend, not even the hope of a phone call from some GM desperate for a savvy veteran to bolster his bench. The calendar was a bleak, empty canvas, leaving Thomas to confront two nagging sensations: the uncertainty of his career, and the constant, debilitating pain in his right hip.

Even for Thomas, whose greatest skill was his ability to defy odds—the 5′ 9″ guard who dominated a game of giants, the last pick of the draft who became an All-Star—this was a daunting, distressing moment. There was no telling when NBA games might return, or whether any team would come calling once that happened. “The toughest time,” Thomas says today, “because I didn’t know what would be next.”

As it happens the nothingness was exactly what he needed. With no games to play and no teams to try out for, Thomas did last May what he should have done three years earlier: He flew to New York, lay down on an operating table and let surgeons repair his fraying hip. There, in the darkest days of the COVID-19 pandemic and the most tenuous stage of his professional life, Thomas took the step that might have saved his career. At least that’s the hope.

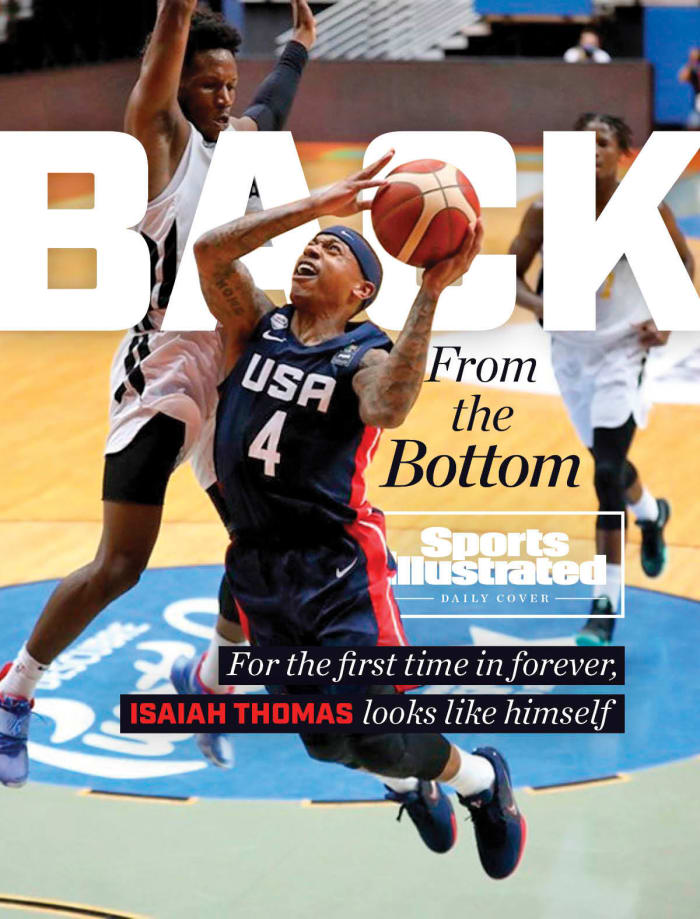

Fast forward to last weekend and Thomas was skipping across a near-empty gym in San Juan, Puerto Rico, swishing deep three-pointers and arcing teardrops, helping lead USA Basketball to a pair of victories in a qualifying tournament for the 2022 FIBA AmeriCup. The venue was unfamiliar, the opponents (The Bahamas and Mexico) unimposing, but for the first time in years, Thomas looked like himself: fluid, joyful, pain-free.

The 32-year-old point guard would finish with 28 points, five assists and seven turnovers over the two games, though the box scores seemed less important than his bounce. The goal now is a return to the NBA, which means persuading at least one team that the Isaiah Thomas of today is a lot closer to the Isaiah Thomas who starred for the Celtics four years ago than the one who limped through the last three seasons with the Cavaliers, Lakers, Nuggets and Wizards.

“I’m moving like I did before the injury,” Thomas says, “and that was the biggest thing I wanted to show people—that I didn’t lose a step. I’m still quick and fast. I’m still powerful. I’m able to move again.”

Some scouts who watched last weekend remain skeptical. They didn’t see enough pop in his game. But since Thomas’s entire career has been predicated on proving everyone wrong, repeatedly, he’s not about to back down now—even after a hip-resurfacing procedure that few pro athletes have endured during their playing days. “My career hasn’t ever been easy,” he says. “I’ve beat the odds before.”

That odds-beating story is by now familiar: Thomas arrived in the NBA in 2011 as the 60th player in a 60-man draft. He was traded twice before finding stardom in Boston, peaking with back-to-back All-Star selections and a fifth-place finish in the 2016–17 MVP race. He averaged 28.9 points per game that season, leading the Celtics on a thrilling run to the Eastern Conference finals.

Like a cursed Shakespearean hero, however, Thomas’s greatest triumph begat his greatest anguish. He initially injured his hip in March 2017, when the Timberwolves’ 6′ 11″, 250-pound Karl-Anthony Towns fell on him, though the severity would not be known until much later. Thomas missed just two of the remaining regular-season games, finished out the year strong, powering the Celtics deep into the playoffs, and then was forced to shut down after reaggravating the injury in Game 2 of the Eastern Conference finals, against LeBron James’s Cavaliers. (Cleveland won the series 4–1.)

Thomas had already dealt with much greater anguish that spring: His younger sister Chyna died in a car accident on the day before the Celtics opened the playoffs against the Bulls. All emotion, he put up 33 points in a 106–102 loss, fighting back the grief with every jumper. From that point on his injury became almost an afterthought. “I think the only reason why I continued to play in the playoffs was because I was going through a real-life situation with my little sister passing,” Thomas says. “And that was the only thing that allowed me to have a clear head, for that two to three hours every time I played. So if I had to do it again, I probably would play again, just because that was the toughest time of my life. And basketball has always been the only thing that can numb whatever I’ve been going through.”

Thomas at his peak, in 2016–17, scored 28.9 points per game and took Boston to the Eastern Conference finals, against Cleveland.

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

Shipped later that summer to Cleveland, Thomas says he holds no grudge against the Celtics, though he contends to this day that the club should have been more forthcoming with him about the extent of his injury and the risks of playing through it. “They could have gone into more detail on what could possibly happen if I continued to play,” he says.

Looking back, Thomas says his greatest regret is not having surgery immediately after the season, or perhaps after the trade. But he was heading toward free agency following the 2017–18 season, which promised his first big payday as a bona fide star. He anticipated a max contract worth as much as $177 million—a massive raise from the $6 million a year he was making at the time. “They better bring out the Brinks truck,” he’d quipped in ’16, after his first All-Star season.

Weighing all of this the prospect of hip surgery and a seven- to eight-month recovery seemed risky, perhaps even foolish. Especially for someone of Thomas’s stature. “There’s not too many 5′ 9″ guys that make the NBA,” he says. “So me taking the time off, I just felt like I would have been overlooked. [Teams] would have been like, ‘O.K., we’ll just find somebody else.’ ”

So Thomas opted to keep playing, to rehab along the way, to grind through the pain and the limitations, to undergo nearly round-the-clock treatment in hopes of delaying surgery long enough to reach that dreamed-of fortune, that Brinks truck. Instead he lasted just half of a season with the Cavaliers before being traded to the Lakers, who wanted nothing but his expiring contract.

“If I could do it over again, I would have got the surgery and sat out that season, and then bet on myself in free agency,” Thomas says now. “I was afraid of, I guess, having to sit so long going into my contract. At the end of the day, I was trying to get paid.”

The cruel twist is that Thomas lost on all counts, allowing his hip and his game to continue eroding while chasing a payoff made impossible by that very injury. He joined the Nuggets in July 2018 on a one-year, $2 million deal, and the Wizards a year later on a similar pact, delaying the inevitable with every short-term gain.

“I just didn’t feel I had the time to sit,” Thomas says. “That’s the scary part about being 5′ 9″ in the best league in the world. You have to be exceptional every time you play. I was just trying to find ways to stay healthy, stay on the court and show that I was capable of playing at a good enough level.”

At his lowest moments, Thomas says, “I fell out of love with the game, because I was in pain every day.”

The last two years were particularly humbling. Thomas played in just 12 games for the Nuggets, who were well-stocked at guard. In Washington last season, he at least carved out a comfortable niche, starting 37 games and averaging 12.2 points in 23.1 minutes while hitting a career-high 41.3% of his three-pointers, a clear sign of his enduring value. “I love him. I love what he’s about,” says Wizards coach Scott Brooks, who brought Thomas in to set an inspiring example for his younger players. “And he did just that. What he did to prepare for a game—a month of NBA games, a year of NBA games—is pretty remarkable. He spent all day to get his body and his mind right. He was fighting every day.”

“I love what he’s about,” Brooks says of Thomas, who in Washington hit a career-high 41.3% of his threes.

Geoff Burke/USA Today Sports

Still, Thomas had clear physical limitations, especially in the halfcourt. His burst was gone. He couldn’t drive by anyone. But his shot was smooth, and Brooks valued his perseverance and leadership. “He was willing to put himself out there, knowing there’s a chance he’s not going to be the same,” the coach says. “He loved the game so much that he was going to do whatever it took to get out there.”

The Wizards nevertheless flipped Thomas to the Clippers last February in a deal that netted Washington a younger prospect, Jerome Robinson. When Los Angeles released Thomas three days later, casting him into the unknown, it was his first time being waived, and it stung. But it pushed him to confront the reality he’d been avoiding. And when the COVID-19 pandemic forced the NBA to shut down last March, Thomas saw an opening: He could get his hip fixed and be healthy in time to start this season.

By the time Thomas finally chose that path, the cartilage in his right hip joint was shot, says Edwin Su, the orthopedic surgeon who performed the procedure at New York’s Hospital for Special Surgery. Thomas had effectively no shock absorption left. “The surfaces of a joint should be nice and smooth, glistening cartilage, like ice,” says Su. But Thomas’s hip “was pitted like asphalt.”

“Unbelievable. It’s a hip that most people can’t even walk on. You’re gonna have daily pain, pain at night, stiffness. … [Some] people have trouble just functioning on a daily basis.”

During that May 6 surgery, doctors resurfaced Thomas’s hip: They trimmed the ball of his femur, capped it with a metal covering and removed damaged bone and cartilage from the hip socket, which itself got a metal shell. In the end, says Su, Thomas was left “mechanically, where he was preinjury.” Now, load sensors indicate that Thomas’s right side is just as strong as his left during athletic activity. From a medical standpoint, “he’s 100%,” opines the surgeon.

Thomas reached the same conclusion with his own gauge: “I can dunk the basketball again. I haven’t dunked s— since three or four years ago.”

By October, Thomas was again scrimmaging five-on-five at home in Seattle, running with NBA veterans Jamal Crawford, Zach LaVine and Marquese Chriss. He worked out for teams last November but got no offers before the new season. When USA Basketball came calling, offering him a showcase alongside the likes of teammates Joe Johnson and Brandon Bass, he pounced on the opportunity.

What scouts saw from Thomas last weekend was a mix of good and bad. He shot well (6 for 12) from three-point range and hit the occasional runner in the lane. But he didn’t drive much or attack with the aggression and explosion that rendered him nearly unguardable at his peak. “What made him so dynamic before was his ability to get to the rim and either finish or get fouled,” says a scout for one Eastern Conference team. “I do not see that anymore.”

Of course, the sample was small, and it was Thomas’s first real competition since surgery. In his own defense he says the absence of a three-second rule in FIBA games, along with the tighter spacing (because of the smaller court and closer three-point line, and with fewer players out by the arc, as you’d see in today’s NBA), left him little room to attack off the dribble. “It would have been forcing the issue,” he says. The explosiveness, he assures, is there when he has to call on it.

“He needs more reps at a high level,” says Tim Manson, Thomas’s trainer. “But he’s not showing any liabilities or any deficiencies at this point.”

And now, Thomas waits once again for the phone to ring. For the next contract, even if it’s a 10-day deal. He says at least three teams have reached out since last weekend, and he’s received supportive texts from NBA peers and former coaches, including the Celtics’ Brad Stevens.

In this strange NBA season with dozens of games postponed by COVID-19 outbreaks and rosters disrupted by contact tracing, there’s always a need for steady veterans and healthy bodies. For the first time in years, Thomas can at least claim that description with confidence. He says he has no specific requirements for his next job—no demands for playing time or shots or even a starting slot—just a chance to show he’s still “one of the best players in the world.”

“I’ve been the last pick. I’ve seen the bottom,” Thomas says. “I’ve seen the top—being an MVP [contender], an All-Star. And I’m back on the bottom now. I just need my foot in the door. Like I said when I got drafted: All I need is a chance. I’ll do the rest.”