Getty Images / Aurich Lawson / Sam Machkovech

We’ve had a lot to say about loot boxes in video games, and in the wake of our own reviews and rants about their growing prominence, regulation and public scrutiny have followed. Researchers have entered the loot box conversation in droves as well, but a new report published by researchers on Friday seeks to answer a key question that it claims has been left untouched by other academics: why do gamers buy loot boxes?

In trying to answer that question, the report, commissioned by gambling-protection advocacy group BeGambleAware, suggests that loot box purchasing motivations are directly correlated with “problem gambling” behaviors. That data drives the report’s conclusion: regulators should apply the same rules to loot boxes that they do to other forms of gambling, because despite seeming differences, they have enough in common to merit stricter controls.

From Skinner boxes to FIFA cards

Much of the study, co-authored by four British universities and one private gambling-research firm, summarizes and describes both the history of loot box monetization and the subsequent blowback, whether from fans, critics, or regulators. The report also outlines the amount of internal regulation done by game companies in response. (Ars was not contacted ahead of this study’s publication, so we only learned today that we are among the outlets cited.)

The study hits a lot of the usual loot box talking points. As the classic Skinner box scenario demonstrated, “variable ratio reinforcement schedules” (VRR, or the expectation that rewards are random) have a different psychological impact than if a player knows what they’re buying outright (a classic loot box trait). Additionally, game makers have been keen to make clear that these boxes’ aesthetic similarities to real-world slot machines (like flashing lights and satisfying sound effects) aren’t accidental.

But those heaps of stories and papers rarely explored the “motivations for loot box purchasing,” today’s report states, which surprised its authors. “This contrasts with gambling research, where we know gambling is driven by a multitude of overlapping motivations,” researchers write. Hence, the report’s biggest findings lie in two tables. The first, which combines data from various existing studies around the English-speaking world totaling 7,771 adults and children, “establishes a significant correlation between loot box expenditure and problem gambling scores.”

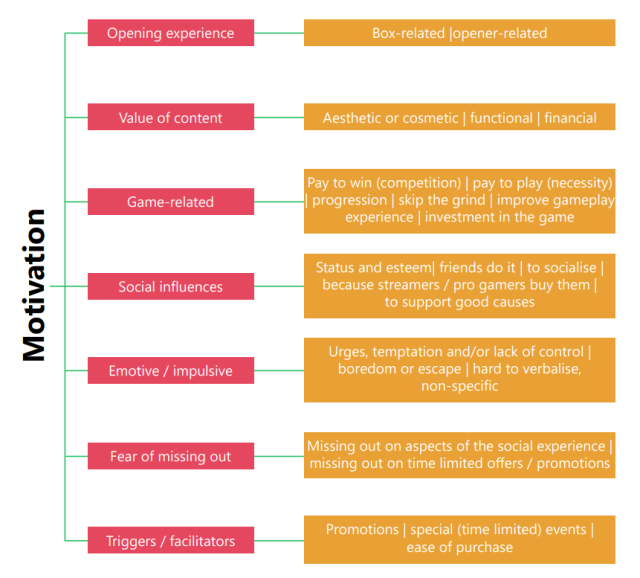

An additional table digs deeper by sending a survey to 441 British gamers, whose answers are as verbose as single-sentence replies; this was followed by drilling down on 28 of these respondents with hour-long interviews. Researchers parsed the interview responses via reflexive thematic analysis to break out motivations for spending money on loot boxes within video games.

BeGambleAware

The above summary image is followed by specific quotes supporting each reasoning. Among those, one quote suggests a “cosmetic” purchase comes with a perceived competitive edge: “You want to compete with the other players, not just in-game, but with your skin.” A number of quotes pointed to the social pressure associated with potential loot box purchases, such as, “You could brag to the lads at work, like: ‘I just packed so and so in a pack last night,'” or deciding with friends in an online session to buy loot boxes simultaneously.

“Existing criteria for gambling regulation”

While that table of potential reasons varies on the psychological spectrum, today’s report points to a key unifying factor: perceived value. That is to say, loot boxes aren’t easily written off as valueless points in a game.

A notion of value “was consistently linked with [in-game] item rarity,” the report states. “The rarer the haul, the higher the value. This might even have direct financial implications, as some participants were hoping to get lucky and unbox items that were available to buy outright in the item shop but were normally too expensive. In some cases, this is the only way players might be able to afford the item. In other cases, they were hoping to later trade any lucky wins for an overall profit. These sorts of observations suggest that many loot boxes meet existing criteria for gambling regulation.”

This statement came with the clarification that “no single dominating motivation” can be ascribed to why players might buy loot boxes. Even so, value is a factor, and the authors determine that loot box purchasing has a statistically significant tie to problem gambling behaviors (“similar or stronger than those between problem gambling and well-established co-morbidities, including depression, drug use, and current alcohol dependence”). The report emphasizes the authors’ stance that regulators should step in, and fast.

They come to this conclusion for a few reasons. First, this report’s authors take great care to dispel the assumed notion that the small percentage of players who buy large amounts of microtransactions like loot boxes (often dubbed “whales”) are necessarily rich. Their data does appear to show that somewhere between 33% and 50% of the highest-spending users, who pay over $100 per month, demonstrate “problematic gambling” patterns. In other words, the data seems to say that big loot box spenders are more likely to have gambling-like tendencies than they are to have high salaries.

“The skew in loot box purchasers—particularly towards those who are younger and male—is particularly concerning when framed alongside the discovery that high spending loot box ‘whales’ tend to be problem gamers, rather than wealthy individuals,” the report continues. “These demographic trends are likely to overlap with psychological drivers, such as impulsivity and gambling-related cognitions. This relationship could result in disproportionate risks for specific groups and cohorts of gamers—suggesting that legislations or controls on loot boxes may have utility for harm minimization.”

“Not beyond the reaches of national powers”

The report’s exploration of what steps regulators might take is a bit murkier, in part because it paints a picture not only of inconsistent European legislation about loot boxes (where games like FIFA have been regulated but similar marketplace activity on Valve’s Steam storefront has not), but also the sneaky steps game makers can take in the face of increased regulatory scrutiny.

“Whatever form policy might take, we need to stay mindful that there is now a whole box of psychological tricks available for unscrupulous developers,” the report says. “Longer-term mitigation of risk, as suggested above, will require more research, new education approaches, and updated consumer protection frameworks. Such recommendations, however, do not preclude policy action on loot boxes.”

Hence, the report leans toward starting with outright bans of paid loot boxes in software—as in, the easily defined practice of “any game-related purchase with a chance-based outcome”—or at least requiring more fully transparent “odds” statements about the likelihood of specific in-game items in those loot boxes (instead of saying that a “legendary” prize has a very low percentage chance of appearing yet leaving out prize-specific sub-percentages, since not all legendary items are equal).

Enforcing such rules wouldn’t be an instant regulatory slam dunk, the report concedes. “At first glance, such observations suggest that regulating all loot boxes as gambling might be a viable solution to avoid the problem of conflicted policy. It would bring all loot boxes under the umbrella of existing gambling regulation—and it is the strategy favored by many, including over 40,000 signatories of a recent UK petition. Such an approach, however, would be a radical overhaul of gambling law—but once again, life is not so easy when it comes to legislative fine-print.” Indeed, a 2019 call from UK Parliament to ban loot boxes has so far failed to bring about wide-spread action.

In spite of potential pitfalls, the report argues that such regulations would at least address specific “money’s worth” statements by game makers and provide more formal provisions for public research and education on manipulative in-game economies. Better regulation could also remind game companies that “when left with few other options (when an industry does not effectively self-regulate), these types of predatory monetization strategies are not beyond the reaches of national powers.”