I remember being convinced a few years ago that Instagram was listening to my real-world conversations. I was at a bar with a friend who was recommending I check out Rumble boxing as a workout, and almost immediately after I was shown an ad for… Rumble boxing. I hadn’t heard about or researched it before, nor had I typed the words Rumble boxing into my phone. Yet somehow, the system knew.

These days, I’m less surprised when Instagram or Google uncannily shows me ads for things I even just think about. I’m not comfortable with it — I’ve just accepted this creepy sense of being stalked as a part of online life. What I search for while shopping on Amazon is going to show up as an ad somewhere completely different later. It’s inevitable.

I can’t definitively prove whether apps on my phone have been eavesdropping on my conversations. But the more likely explanation is that they’re eerily smart because of the data they’ve gleaned through third-party cookies.

Cookies are bits of information stored on your hard drive that a website can access. First-party cookies enable sites to remember your username and the fact that you’ve entered a correct password, for example, so it can keep you logged in while you browse. It can also remember your preferred theme and other details you save in a user profile.

#Urban-Photographer via Getty Images

Third-party cookies, however, are not created by the people who made the page. They usually come from advertisers and sit on banners placed on sites across the web. When you encounter one, it identifies you with a unique ID, then stores information that each site’s owner chooses to share. This could be anything from your location and what you put in your shopping cart to your email address.

Of course, after the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) laws went into effect three years ago, there’s been more transparency. Even users in the US encountered noticeable changes, thanks to the pop-ups on every website asking us to consent to trackers. But the internet hasn’t gotten less creepy.

With recent news about Google committing to disabling third-party cookies in Chrome, though, it seems like the internet as we know it is about to undergo a seismic shift — at least behind the scenes. If everything goes according to plan (whatever that may be), the average user shouldn’t notice much of a difference.

The promise is that without third-party cookies tracking your every move it should feel less like companies are constantly invading your privacy. If you look up roach killers on a whim, you shouldn’t be subjected to ads about pesticides everywhere for days after.

That sounds like a dream for those who hate being tracked. For advertisers and small businesses, though, this is at best a major inconvenience and at worst potentially crippling.

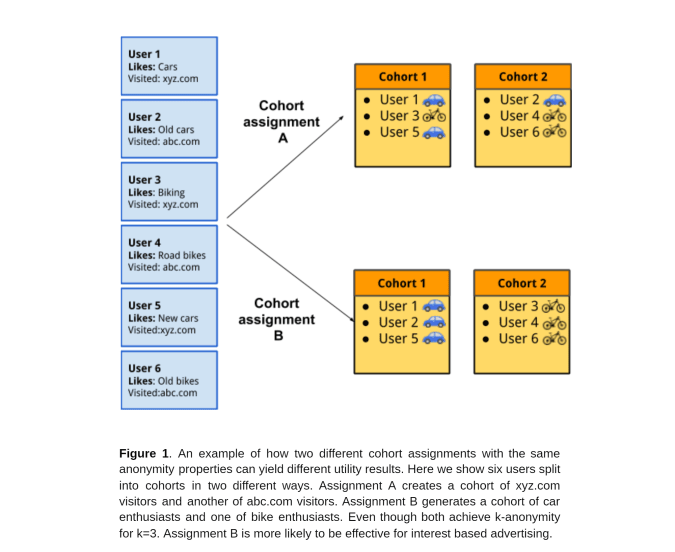

Some of those changes are already here. Google has announced it’s begun trials for an approach called Federated Learning of Cohorts (FLoC, pronounced “flock”), which categorizes users into groups of at least 1,000 people based on their tastes. If a company making plant-based milks wants to target people who love vegan recipes, for example, it can choose to serve ads to that cohort.

Google Research & Ads

Meanwhile, Safari already started blocking all third-party cookies by default in March 2020. Apple went on to announce new app-tracking policies for iOS 14 three months later. That December, Facebook published a statement in response, titled “Speaking Up For Small Businesses.” In it, vice president for Ads and Business Products Dan Levy wrote “Apple’s new iOS 14 policy will have a harmful impact on many small businesses that are struggling to stay afloat and on the free internet that we all rely on more than ever.”

Levy is effectively saying that the internet as we know it is free thanks to ads. The idea is that without ads, services that are free today may have to start charging users. And if ads aren’t relevant or personalized, they might be less effective, which will in turn spur marketers to run more of them. That increase in the volume of ads would not only be annoying for the average internet surfer, but would also cost businesses more money.

Most major tech companies agree it’s important to give advertisers a way to serve relevant ads, but they also say protecting user privacy is a top priority. Microsoft and Mozilla quickly followed Apple’s lead and have both disabled third-party cookies by default on their browsers, while Google is trailing behind with Chrome only set to do that in 2022.

The race is now on to find a suitable alternative to third-party cookies that would allow marketers some level of precision and personalization without sacrificing user privacy. Several proposals are currently being considered, including Google’s Privacy Sandbox, which is a suite of suggestions including FLoC. Considering Chrome is the most popular browser around, Google has a lot of influence over what the internet ends up using.

NurPhoto via Getty Images

There are other recommendations being considered, though, and for some odd reason they’ve all been given avian names. In addition to Google’s FLoC, Microsoft has offered Parakeet, which stands for “Private and Anonymized Requests for Ads that Keep Efficacy and Enhance Transparency.” It makes the browser responsible for anonymizing content before sending it to ad networks, which use that data to show relevant ads to users.

Meanwhile, a group of online advertisers came up with SWAN or Secure Web Addressability Network. It focuses on giving users full control and transparency over who gets to see their data. Also in the running: Turtledove and Sparrow, which stand for “Two Unrelated Requests, Then Locally Executed Decision On Victory” and “Secure Private Advertising Remotely Run on Webserver” respectively.” (I know.)

These are all just proposals for now, and whether they get adopted depends on what the internet’s biggest players decide to pick. They work together with groups like the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB), the Partnership for Responsible Addressable Media (PRAM) and the World Federation of Advertisers (WFA) to evaluate the potential alternatives. Wendy Seltzer, strategy lead at the W3C, chairs her organization’s “Improving Web Advertising” business group and is working with the Privacy Community Group on coming up with standards. “We’ve seen a few different classes of proposals,” she told Engadget.

According to Seltzer, some of these proposals are about standard cross-browser features, while others before her group are “about providing information that is not individually identifying but still useful to advertisers and marketers that can offer additional support for monetizing without invading privacy.”

Altayb via Getty Images

The latter class of measures are about still being able to understand the preferences and actions of each user without getting personally identifiable information (PII). One of these proposed methods is cohort-based (like FLoC), which groups users into categories with 1,000 people or more. If you’ve been classified as someone who likes sports apparel, for example, marketers can choose to serve ads about Lululemon or Under Armor’s next sale. But they won’t know what other websites you’ve visited or what shoes you stuck in your shopping cart earlier that day.

Another approach is SWAN, and it’s being presented by a group of online advertisers. Key to the SWAN method is the Secure Web ID (SWID), which is a unique identifier for each browser. SWAN’s focus is more about prioritizing transparency, having the user choose whether to agree to sharing their data and telling them exactly which sites will receive their information. Then, marketers who want to serve ads using that will also have an encrypted ID used to access the information. This encryption requirement on all parties, according to SWAN founding member Hardeep Bindra, “acts as an audit trail.” It’ll show who received the data, whether they were a publisher or vendor and if it was used “with the individual’s privacy choices,” he told Engadget.

Something both Seltzer and other executives at major internet companies I spoke with on background highlighted is that the use of third-party cookies today didn’t happen intentionally. “The general sense is that third-party cookies were an accident that became a feature,” Seltzer said. As a result, there was no real oversight over whether their implementation infringed on consumer privacy.

But the concern and attention around the removal of third-party cookie support will likely ensure that what takes its place will come under more scrutiny. With the public pressure to prioritize user privacy, it’s possible that new methods being proposed will be more carefully thought out. As a Mozilla spokesperson told Engadget: “Advertising and privacy can co-exist. The advertising industry can operate differently. It does not have to violate people’s privacy. And yet for years that’s the direction the industry has headed.”

Oleg Mishutin via Getty Images

Of course, given Chrome is the most popular browser out there, what Google chooses has a strong chance of being adopted by most advertisers. But it’s also important to note that while companies like Apple, Microsoft and Mozilla do participate in discussions with the W3C, they don’t appear to have supported a proposal. Instead, Safari uses something called Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP) to block trackers, while Firefox and Edge have their own version called Enhanced Tracking Protection (ETP). It’s not yet clear what these tracking prevention programs will do with the bird-themed proposal that ultimately wins favor with advertisers across the web.

But even though it’s too early to tell if FLoC, Parakeet or SWAN will become the internet’s new favorite ad-serving mechanism, most people I spoke with already agree on one thing: Browsing the internet in 2022 won’t look much different than it does today. But if advertisers and browser makers have done their jobs right you should feel less like you’re being stalked.

“It doesn’t need to be a web that looks different but it can be a web where users have more confidence that their privacy wishes are respected,” Seltzer said. There likely won’t be any visual changes on the user side of things. While the W3C tends to “stay away from specifying the user interface,” Seltzer said, she believes developers won’t want to “bombard users with information unless it’s something they can do something with.”

Bindra also highlighted “consent fatigue” as something SWAN wants to avoid. Instead of having to agree to or decide how every individual site uses cookies to store your data a la GDPR-compliant pages today, SWAN proposes that the user pick a global permission setting that would govern all participating sites. You’d see who all the participants are that have access to the data you’ve granted SWAN access to, as well as decide what types of information to share.

SWAN is a relatively new proposal, though, and it’s not clear yet how much support it will get. While some of the other ideas focus on trying to understand user preferences without tracking, SWAN would still collect some data. Regardless, the burden of getting information to serve relevant ads without third-party cookies will fall on the shoulders of marketers and developers. The average user likely won’t notice much of a difference. “There will be lots of work to communicate to developers who need to be using newer technologies but probably not banners for end users,” Seltzer said.

Part of that tracking-free future is already here, especially if you use Safari, Edge or Firefox as your primary browser, since third-party cookies are already disabled in those. As these changes also roll out to apps on your phone, hopefully you won’t see ads for something you’ve just searched for out of curiosity any more. We can all go back to feeling safer about our random searches for asinine stuff.