Vivaldi

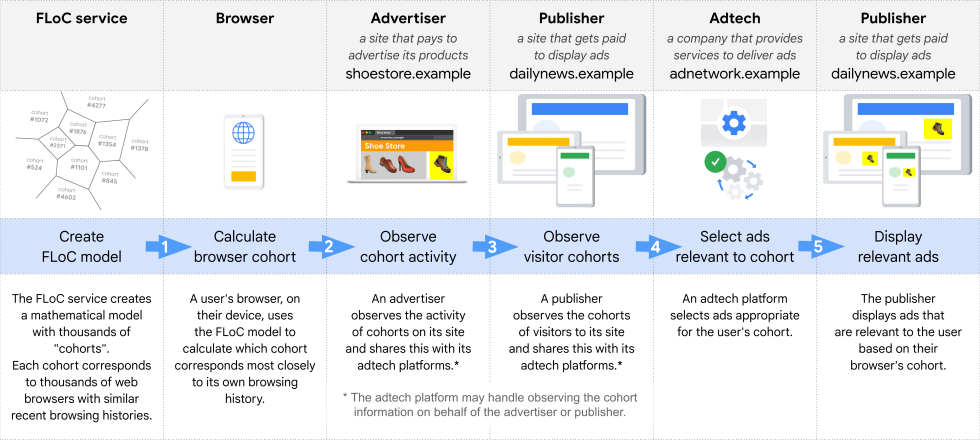

Google wants to kill third-party tracking cookies used for ads in Chrome with the “Chrome Privacy Sandbox.” Since Google is also the world’s largest ad company, though, it’s not killing tracking cookies without putting something else in its place. Google’s replacement plan is to have Chrome locally build an ad interest profile for you, via a system called “FLoC” (Federated Learning of Cohorts). Rather than having advertisers collect your browsing history to build an individual profile of you on their servers, Google wants to keep that data local, and have the browser to serve a list of your interests to advertisers whenever they ask via an API, so that you’ll still get relevant ads. Google argues that conscripting the browser for ad interest tracking is a win for privacy, since it keeps your exact browsing history local and only serves up anonymized interest lists. Google does not have many other companies in its corner, though.

One of the first to come out against Google’s plan was the EFF, which in March wrote a blog post called, “Google’s FLoC is a Terrible Idea.” The EFF seems to be against user tracking for ads entirely, saying Google’s framing of the issue “is based on a false premise that we have to choose between “old tracking” and “new tracking.”

“It’s not either-or,” the EFF writes. “Instead of re-inventing the tracking wheel, we should imagine a better world without the myriad problems of targeted ads.” The EFF worries that FLoC won’t stop advertisers from personally identifying people and that the API will serve up full profile data on first contact with a site, saving tracking companies from having to do the work of building a profile themselves over time. It also argues that “the machinery of targeted advertising has frequently been used for exploitation, discrimination, and harm.”

Google’s browser competitors have also come out against FLoC. Mozilla told The Verge ” We are currently evaluating many of the privacy preserving advertising proposals, including those put forward by Google, but have no current plans to implement any of them at this time.” The Firefox developer continued “We don’t buy into the assumption that the industry needs billions of data points about people, that are collected and shared without their understanding, to serve relevant advertising.”

As for the other major independent browser vendor, Apple, it’s hard to imagine it would be onboard with FLoC given how pro-privacy, anti-ad network it has been in the past. While it doesn’t have an official statement out, Webkit (Safari’s rendering engine) Engineer John Wilander has said the WebKit team “have not said we will impliment [FLoC] and we have our tracking prevention policy.”

Next, up how do the many forks of Chromium feel about FLoC? A “no” here would mean tearing the code out of your browser codebase. The Verge also pinged Microsoft about its feelings, and got a long, meandering answer that I don’t think boils down to a clear “yes” or “no” to FLoC:

We believe in a future where the web can provide people with privacy, transparency and control while also supporting responsible business models to create a vibrant, open and diverse ecosystem. Like Google, we support solutions that give users clear consent, and do not bypass consumer choice. That’s also why we do not support solutions that leverage non-consented user identity signals, such as fingerprinting. The industry is on a journey and there will be browser-based proposals that do not need individual user ids and ID-based proposals that are based on consent and first party relationships. We will continue to explore these approaches with the community. Recently, for example, we were pleased to introduce one possible approach, as described in our PARAKEET proposal. This proposal is not the final iteration but is an evolving document.

Brave has a whole post out about why it disables FLoC, saying it’s harmful to users and “a step in the wrong direction,” citing many of the same concerns the EFF has. The Vivaldi browser also has a blog post (and the above graphic) detailing why it won’t support FLoC, saying “Google’s new data harvesting venture is nasty” and “a dangerous step that harms user privacy.”

There have been some reports out there that WordPress, which powers something like 34 percent of all websites on the internet, will block FLoC, but that is just a proposal submitted by one of its contributors. WordPress’s founding developer, Matt Mullenweg, says the company has not made any “hasn’t made any decisions or changes yet” on FLoC.

DuckDuckGo, one of Google’s search engine rivals, has also come out against FLoC, and in addition to disabling it on the search pages, has released a Chrome extension that blocks FLoC tracking across the web. I don’t think I’ve seen a single company other than Google claim that FLoC is a great idea.

FLoC is currently rolling out as a trail in Chrome, and, as of March 30, is enabled for “0.5% of Chrome users.” The EFF’s amifloced.org site will let you know if you’re one of the lucky few.

Part of the uh, “magic” of Chrome is that, if Google’s doesn’t see value in reaching an industry-wide consensus, Google doesn’t really need anyone else’s cooperation when it comes down to it. Chrome has something like 70 percent of the browser market share. Google controls the world’s biggest ad network. These ads are shown on some of the world’s most popular websites, which Google also controls, like Google.com (#1 in the world) and YouTube (#2). The ads are also shown on the world’s most popular operating system, Google’s Android, which has over 2.5 billion monthly active users. There’s also Chrome OS, which is now the second most popular desktop OS, and is particularly successful in schools. The company regularly sneaks out its own web “standards” first in the Google ecosystem, like early rollouts of WebP, VP8/9, and SPDY/HTTP/2, and it could, if it wanted to, do the same with FLoC.