While US lawmakers muddle through yet another congressional hearing on the dangers posed by algorithmic bias in social media, the European Commission (basically the executive branch of the EU) has unveiled a sweeping regulatory framework that, if adopted, could have global implications for the future of AI development.

This isn’t the Commission’s first attempt at guiding the growth and evolution of this emerging technology. After extensive meetings with advocate groups and other stakeholders, the EC released both the first European Strategy on AI and Coordinated Plan on AI in 2018. Those were followed in 2019 by the Guidelines for Trustworthy AI, then again in 2020 by the Commission’s White Paper on AI and Report on the safety and liability implications of Artificial Intelligence, the Internet of Things and robotics. Just as with its ambitious General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) plan in 2018, the Commission is seeking to establish a basic level of public trust in the technology based on strident user and data privacy protections as well as those against its potential misuse.

OLIVIER HOSLET via Getty Images

”Artificial intelligence should not be an end in itself, but a tool that has to serve people with the ultimate aim of increasing human well-being. Rules for artificial intelligence available in the Union market or otherwise affecting Union citizens should thus put people at the centre (be human-centric), so that they can trust that the technology is used in a way that is safe and compliant with the law, including the respect of fundamental rights,” the Commission included in its draft regulations. “At the same time, such rules for artificial intelligence should be balanced, proportionate and not unnecessarily constrain or hinder technological development. This is of particular importance because, although artificial intelligence is already present in many aspects of people’s daily lives, it is not possible to anticipate all possible uses or applications thereof that may happen in the future.”

Indeed, artificial intelligence systems are already ubiquitous in our lives — from the recommendation algorithms that help us decide what to watch on Netflix and who to follow on Twitter to the digital assistants in our phones and the driver assist systems that watch the road for us (or don’t) when we drive.

“The European Commission once again has stepped out in a bold fashion to address emerging technology, just like they had done with data privacy through the GDPR,” Dr. Brandie Nonnecke, Director of the CITRIS Policy Lab at UC Berkeley, told Engadget. “The proposed regulation is quite interesting in that it is attacking the problem from a risk-based approach,” similar to that used in Canada’s proposed AI regulatory framework.

These new rules would divide the EU’s AI development efforts into a four-tier system — minimal risk, limited risk, high risk, and banned outright — based on their potential harms to the public good. “The risk framework they work within is really around risk to society, whereas whenever you hear risk talked about [in the US], it’s pretty much risk in the context of like, ‘what’s my liability, what’s my exposure,’” Dr. Jennifer King, Privacy and Data Policy Fellow at the Stanford University Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, told Engadget. “And somehow if that encompasses human rights as part of that risk, then it gets folded in but to the extent that that can be externalized, it’s not included.”

Flat out banned uses of the technology will include any applications that manipulate human behavior to circumvent users’ free will — specifically those that exploit the vulnerabilities of a specific group of persons due to their age, physical or mental disability — as well as ‘real-time’ biometric identification systems and those that allow for ‘social scoring’ by governments, according to the 108-page proposal. This is a direct nod to China’s Social Credit System and given that these regulations would still theoretically govern technologies that impact EU citizens whether or not those folks were physically within EU borders, could lead to some interesting international incidents in the near future. “There’s a lot of work to move forward on operationalizing the guidance,” King noted.

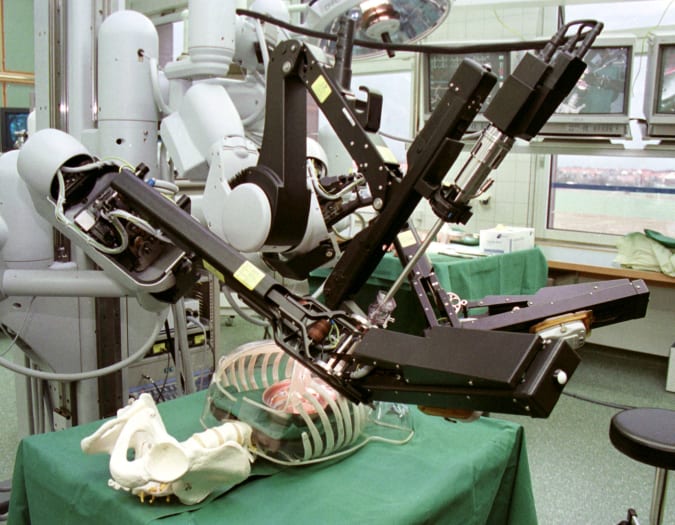

Jochen Eckel / reuters

High-risk applications, on the other hand, are defined as any products where the AI is “intended to be used as a safety component of a product” or the AI is the safety component itself (think, the collision avoidance feature on your car.) Additionally, AI applications destined for any of eight specific markets including critical infrastructure, education, legal/judicial matters and employee hiring are considered part of the high-risk category. These can come to market but are subject to stringent regulatory requirements before it goes on sale such as requiring the AI developer to maintain compliance with the EU regs throughout the entire lifecycle of the product, ensure strict privacy guarantees, and perpetually maintain a human in the control loop. Sorry, that means no fully autonomous robosurgeons for the foreseeable future.

“The read I got from that was the Europeans seem to be envisioning oversight — I don’t know if it’s an overreach to say from cradle to grave,” King said. “But that there seems to be the sense that there needs to be ongoing monitoring and evaluation, especially hybrid systems.” Part of that oversight is the EU’s push for AI regulatory sandboxes which will enable developers to create and test high-risk systems in real world conditions but without the real world consequences.

“These measures are intended to prevent the sort of chilling effect that was seen as a result of the GDPR, which led to a 17 percent increase in market concentration after it was introduced,” Jason Pilkington recently argued for Truth on the Market. “But it’s unclear that they would accomplish this goal.“ The EU also plans to establish a European Artificial Intelligence Board to oversee compliance efforts.

Nonnecke also points out that many of the areas addressed by these high-risk rules are the same that academic researchers and journalists have been examining for years. “I think that really emphasizes the importance of empirical research and investigative journalism to enable our lawmakers to better understand what the risks of these AI systems are and also what the benefits of these systems are,” she said. One area these regulations will explicitly not apply to are AIs built specifically for military operations so bring on the killbots!

Ben Birchall – PA Images via Getty Images

Limited risk applications include things like chatbots on service websites or featuring deepfake content. In these cases, the AI maker simply has to inform users up front that they’ll be interacting with a machine rather than another person or even a dog. And for minimal risk products, like the AI in video games and really the vast majority of applications the EC expects to see, the regulations don’t require any special restrictions or added requirements that would need to be completed before going to market.

And should any company or developer dare to ignore these regs, they’ll find out that running afoul of them comes with a hefty fine — one that can be measured in percentages of GDP. Specifically, fines for noncompliance can range up to 30 million euros or 4 percent of the entity’s global annual revenue, whichever is greater.

“It’s important for us at a European level to pass a very strong message and set the standards in terms of how far these technologies should be allowed to go,” Dragos Tudorache, European Parliament member and head of the committee on artificial intelligence, told Bloomberg in a recent interview. “Putting a regulatory framework around them is a must and it’s good that the European Commission takes this direction.”

Whether the rest of the world will follow Brussell’s lead in this remains to be seen. With the way the regulations currently define what an AI is — and it does so in very broad terms — we can likely expect to see this legislation to impact nearly every aspect of the global market and every sector of the global economy, not just in the digital realm. Of course these regulations will have to pass through a rigorous (often contentious) parliamentary process that could take years to complete before it is enacted.

And as for America’s chances of enacting similar regulations of its own, well. “I think we’ll see something proposed at the federal level, yeah,” Nonnecke said. “Do I think that it’ll be passed? Those are two different things.”

All products recommended by Engadget are selected by our editorial team, independent of our parent company. Some of our stories include affiliate links. If you buy something through one of these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.