Last December, on the wall of Jalen Green’s sparsely decorated two-bedroom Walnut Creek, Calif., apartment, a 40-inch TV glowed. Most nights, college basketball flickered across the screen. Auburn games, occasionally. Unbeaten Gonzaga, often. Oklahoma State, led by friend Cade Cunningham, whenever possible. From his couch, Green would text and FaceTime friends and former teammates across the country. He knew what he was missing.

A year ago Green, a smooth 6′ 5″ combo guard, was a five-star prospect at San Joaquin Memorial High in Fresno. His life, virtually all 19 years of it, was chronicled in YouTube documentaries. Stories about him—such as how he taught himself to dunk in the summer before eighth grade because his stepfather, Marcus Greene, promised to buy him a pair of Air Jordans once he could—had become folklore. Green had verbally committed to Auburn, determined to light up the SEC for a year before making the jump to the pros. Cunningham, sweeping freshman honors? That could have been him. Evan Mobley, building his rep during USC’s deep run in the NCAA tournament? Ditto. Instead, Green—the other candidate to be taken first in the NBA draft—chose a different route, and suddenly the world’s most visible prep star had all but vanished.

As college basketball plowed on through the pandemic, Green was in Walnut Creek, an Oakland suburb, organizing a shoe rack, hanging LED lights in his living room, watching the tube and waiting for his chance. Last April, Green signed on to play for the Ignite, an experimental G League team that offered top high school prospects mid-six-figure salaries to play a 15-game schedule. A raft of blue-chippers joined him: Jonathan Kuminga, Isaiah Todd and Daishen Nix, as well as international projects Kai Sotto (a 7′ 3″ center from the Philippines) and Princepal Singh (a 6′ 9″ forward from India). Says Green of his decision, “I want to play in the NBA. I want to be Rookie of the Year. To me, this was the best way to do that.”

It’s mid-May, and Green is speaking via Zoom from a rented home in Los Angeles, two months after the Ignite’s pandemic-shortened season ended. Green averaged 17.9 points, playing NBA-caliber defense and displaying sharp three-point shooting (36.5%). Green, who poured in 30 in a playoff loss to Raptors 905, admits: The season was stressful at times. He reported to the team in late August. He quarantined and took COVID-19 tests every day. His life consisted of shuttles from his apartment to practice and back. Excitement was a trip to the supermarket for takeout crab cakes. He didn’t play meaningful games until February. “I wish we could have been hooping more,” says Green. “But looking back, it was a great experience.”

The Ignite debuted last year, but their roots date back to the April 2018 report issued by the Commission on College Basketball—a 14-member body formed by the NCAA and chaired by Condoleezza Rice—after widespread recruiting scandals rocked Division I. The 53-page report mentioned the NBA 86 times, sharply criticizing the league’s age minimum, which kept U.S. players from being draft-eligible until one year after their high school class graduated. Known as the one-and-done rule, the regulation, according to the commission, “played a significant role in corrupting and destabilizing college basketball, restricting the freedom of choice of players and undermining the relationship of college basketball to the mission of higher education.” The commission also encouraged the NBA to create a more viable alternative for elite prep players.

Since the founding of the G League (formerly known as the D-League) in 2001, the NBA had tinkered with ways to make it more appealing to players. But bumping up the average salary, even introducing $125,000 deals for select prospects, proved unsuccessful; the lure of the NCAA tournament, of wearing a Duke or Kentucky jersey—if only for a season—was too strong. Players who didn’t go to college didn’t go to the G League, either. In ’08, Brandon Jennings took a reported seven-figure deal in Italy. Emmanuel Mudiay opted for China in ’14. Last season LaMelo Ball and R.J. Hampton played in a league in Australia.

Shareef Abdur-Rahim, the G League’s president since December 2018, was a one-and-doner himself, turning pro after his freshman year at Cal. There, the 6′ 9″ forward got a taste of the NBA game when former Bears stars Jason Kidd or Lamond Murray would drop in, or in occasional scrimmages with the Warriors. “That was my introduction,” says Abdur-Rahim. The No. 3 pick in the 1996 draft, he averaged 18.7 points as a rookie, though he says a G League option “would have been good, just because it would have been a slower step into the NBA.”

To lure top players, the Ignite needed money, and the NBA (which pays all G League player salaries) was willing to commit it. But Abdur-Rahim wanted to offer more. Media training. Access to financial literacy training. Zoom sessions with ex-players and parents of players to provide a deeper understanding of the NBA lifestyle. For decades, college basketball has operated as the NBA’s de facto farm system, but the league could exert no control over it. The Ignite would be a true developmental team, singularly focused on preparing prospects for the next level. If it was successful.

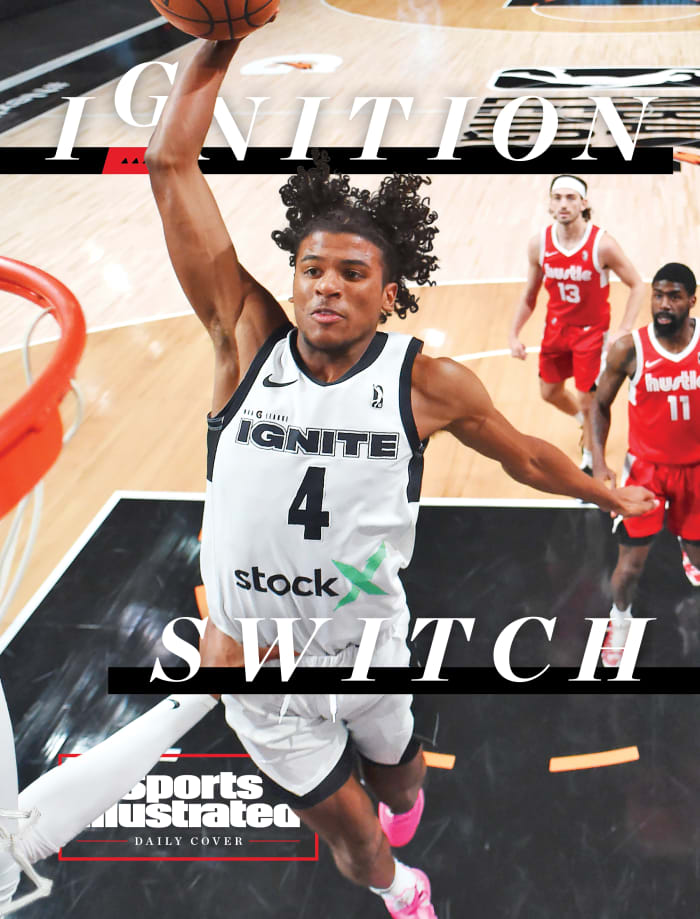

Scouts say Green needs to work on his playmaking and D, but he’s still a top-three talent.

Juan Ocampo/NBAE/Getty Images

In late April 2020, Brian Shaw’s phone buzzed. Shaw’s relationship with Abdur-Rahim dates back to the mid-1990s, when Shaw, an Oakland native early in his NBA career, would play pickup games in the summer at Berkeley. The two remained connected, routinely working out together during the offseason. When it came time to find a coach for the Ignite, Shaw, unemployed after a three-year stint as an assistant with the Lakers ended in ’19, was the first name Abdur-Rahim thought of.

Shaw thought the concept was appealing. During his first stint as a Lakers assistant in 2005, L.A. drafted Andrew Bynum, a 17-year-old 7-footer from New Jersey who averaged just 7.3 minutes in the 46 games he got off the bench as a rookie. Shaw was there in ’16 and ’17 when the Lakers spent lottery picks on Brandon Ingram and Lonzo Ball, one-and-done college stars who, while talented, “weren’t necessarily prepared [for the NBA], or, in some cases, [weren’t] the most professional,” Shaw says. In recent years he had moonlighted as a talent evaluator for Nike. At the Nike Hoop Academy, he coached Green, Kuminga and Todd. He was intrigued that Abdur-Rahim’s offer gave him the opportunity to work with younger players.

The pandemic, of course, complicated the start of the season. Shaw sought to simplify things. He banned friends, family and agents from the Ignite facilities and apartment complex. “Gregg Popovich is not going to be taking a phone call or directions from a parent about how they feel their son should be played,” says Shaw. “I wasn’t going to have that, either.” He ran NBA-style practices, emphasizing off-the-ball movement. “Each one of these guys has been ‘the man’ on every team they have played on,” says Shaw. “But no coach in the NBA is going to let them dribble that much.” He reminded them of a lesson he learned from Tex Winter, the longtime Phil Jackson assistant and architect of the triangle offense. “There’s five players on the court, and there’s only one basketball,” says Shaw. “That means you have the ball only 20% of the time in your hands. You have to learn how to play the other 80% of the time when you don’t.”

The players watched film. A lot of it. An hour, daily, as a team. And then, three nights a week, mandatory individual sessions. Shaw asked each one: Who is your idol? Whomever they answered, Shaw would pull clips and watch the tape with them. As he got to know them, Shaw would add film of players he thought they should study. With Green, who was always asking for more film, it was Kobe Bryant, Paul George and Anfernee Hardaway. (“I wanted him to watch their footwork,” says Shaw.) With Kuminga, it was Celtics swingman Jaylen Brown. (“Same body type, same athleticism, both two-way players.”) With Todd, it was Cliff Robinson, who had an 18-year career, and Jerami Grant, who broke out this season with the Pistons. (“Grant wasn’t highly touted. But with hard work, he got a nice contract and became a featured player.”)

Kuminga will contribute right away on D but will need to become a more efficient shooter.

Juan Ocampo/NBAE/Getty Images

Shaw could tell them what to do. Abdur-Rahim needed veteran teammates who could show them. He recruited Jarrett Jack, a 13-year NBA point guard coming off a torn ACL. And Bobby Brown, an overseas stalwart who also played four NBA seasons. And Amir Johnson, a big man with 14 years of NBA experience. Abdur-Rahim told them: I need you to play. But I need you to teach, too. “His message was ‘Be a vet,’ ” says Johnson. “Show them the ropes. Let them know what the next stage is like.”

Johnson understood them. He was, in fact, the last player drafted straight out of high school, joining a Detroit team coming off an NBA championship in 2005. He didn’t have a driver’s license. He didn’t own a suit. He leaned on Antonio McDyess, Chauncey Billups and Ben Wallace for guidance. “I could have used a development league,” says Johnson, laughing. “I didn’t know anything.”

Quarantined, Johnson, 34, found himself surrounded by teenagers eager for information. Games of dominoes and spades and video game battles often went on for hours. They talked basketball. They talked life. Johnson emphasized the importance of developing a routine. Wallace always lifted weights before games. Bryant always got in extra shots. For Johnson, it was getting an early workout in before practice—and a solid nap before every game. “Whatever you do, you want to stick with it for your whole career,” says Johnson. “Build habits. Always remember what got you to this position.”

Shaw knew the Ignite were talented. He was equally sure that wouldn’t translate to wins. “I tried to make [G League execs] understand early that we are going to get our asses handed to us more times than not,” says Shaw. The star players were teenagers in a league filled with men, all of whom were eager to take down a team of hyped prospects. In December the Ignite scrimmaged a group of G League veterans. They lost the first game by six, the second by 26. Green, who had been playing pickup games against pros at UCLA for years, found himself hesitant. “It was a lot faster,” he recalls. “Guys were stronger. And you can’t hesitate against grown men. Those games, man—you knew you were not in high school anymore.”

Shaw learned something in the scrimmages, too. He started mixing the veterans with the prospects. He staggered minutes. He pulled Todd and Nix from the starting lineup, inserting Johnson and Jack. “It kept them from cannibalizing each other at the start of every game,” says Shaw. He assured Todd and Nix that when it came time to close games, they would both be on the floor. When the Ignite reported to the Orlando bubble in mid-February, they were more balanced. They won four straight to start the season. In a fortified G League field—11 teams chose not to go to Orlando, leaving the 17 teams that did to divvy up their top talent—the Ignite went 8–7 before dropping their lone playoff game. Kuminga averaged 15.8 points. Nix handed out 5.3 assists. Lost just months earlier, they closed the season confident, and with an identity. “We just needed time,” says Kuminga. “We needed to play games together. Once we did, we figured out the rest.”

Asked about the Ignite’s future, Abdur-Rahim is evasive. He points to the success of the blue-chippers: Green and Kuminga are projected to be top-five picks, and Todd and Nix could go in the second round. “And they didn’t have to go outside of our NBA system to grow and develop,” says Abdur-Rahim. A pair of five-star recruits—Michael Foster Jr., a 6′ 9″ forward from Hillcrest Prep in Milwaukee, and Jaden Hardy, a 6′ 4″ combo guard from Henderson, Nev.—have signed on for next season. And more are expected to come. Shaw plans to return as coach, with the hope that an end to the pandemic will provide an even more productive environment.

The landscape, though, is evolving. The NBA is expected to eliminate the one-and-done rule in its next collective bargaining agreement, perhaps as early as 2023, reopening its doors to high school players. If it does, the caliber of talent the Ignite could attract is murky. Nor is it clear how long NBA owners will want to continue footing the bill. “It’s hard to say where it goes,” says Abdur-Rahim. “But we feel good that we have something that is sustainable.”

Toward the end of a call, Green, peering through a computer screen, offered his endorsement. He noted that he added five pounds of muscle during his time with the Ignite. He corrected an issue with his footwork and gained valuable reps shooting behind the NBA three-point line. A point guard in high school, Green spent most of his time with the Ignite playing off the ball. He also took advantage of the G League’s off-court offerings, establishing an LLC and seeing a therapist for the first time. “I was used to being sheltered,” says Green. “I feel like I’m more disciplined. I learned how to grow up.”

And if a high school star called him and said he was considering the G League option?

“I would ask him what his goal is in the basketball world,” says Green. “And then I’d tell him, ‘Is this something you really want to do?’ I would make sure that this is all up to him … because a lot of people get it twisted like, ‘Oh, it’s for the money. It’s for the money.’ You have no idea why we’re doing it. I’m trying to get to the league. I’m trying to build my name up and be one of the best.”

The Ignite, it seems, have pointed him in that direction. Above the door in his Walnut Creek apartment was a yellow Post-it note. When he moved in, Green wrote down a list of goals. He can’t recall exactly what they were, just that he crossed them all off—except one. “Be the No. 1 pick,” says Green, smiling. Who knows? He may get to cross that one off, too.

More NBA Coverage:

• How It Feels to Watch The Team You Built Thrive Without You

• Ben Simmons’s Flaws Laid Bare In Potential End of the Process

• What’s At Stake in the NBA Draft Lottery?