It comes with a lousy risk-reward ratio, sideline reporting does. One technical glitch, one awkward interaction, one Gatorade bath, one Gregg Popovich … and you become embalmed as a meme, sacrificed before the altar of YouTube. On the other hand, do your job capably and without a hiccup? Best-case scenario: It generally yields a forgettable segment, a few bits of sports boilerplate, and, then, “Thanks, coach. Back to you in the booth, guys.”

Every now and then, though, the sideline reporter mines television gold, an interaction both entertaining and revelatory. Which happened to ABC/ESPN’s Holly Rowe on Dec. 5. On that Saturday afternoon, the Indiana football team was in Madison for its annual assignation with the Badgers. Not only was Indiana without its starting quarterback, Michael Penix Jr., who tore his ACL the previous week against Maryland, but Indiana was, well, Indiana, a perennially lousy program. The game, in fact, marked the 10-year anniversary of Indiana’s losing to Wisconsin by the score of 83–20.

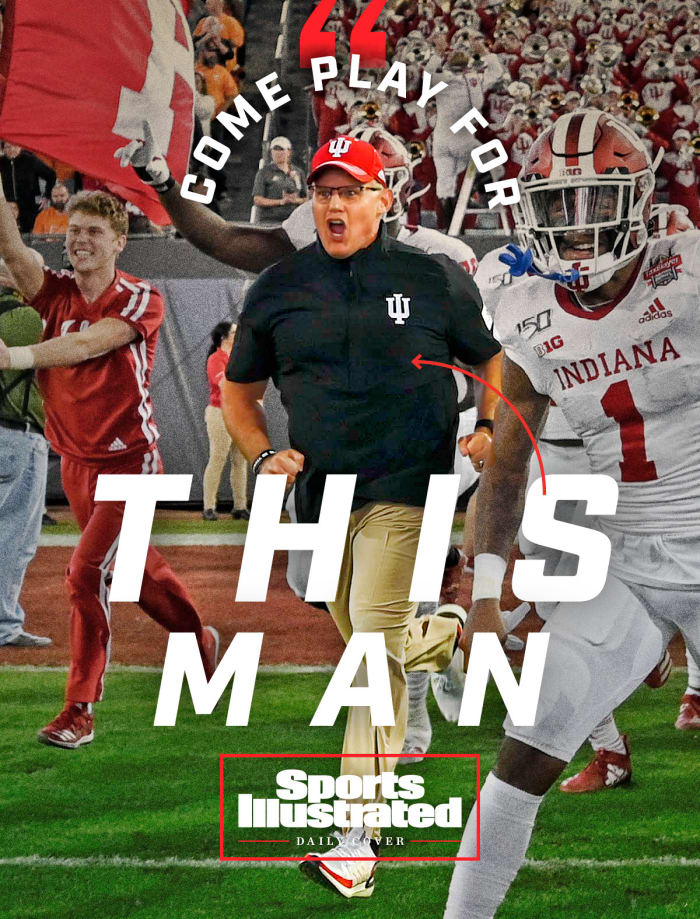

Yet in this sideways, COVID-19-addled season, Indiana held off the Badgers, 14–6, improbably pushing its record to 6–1. Rowe maneuvered her way to Indiana’s end of the field for a change, and positioned herself (and socially distanced herself) before interviewing the Hoosiers’ head coach, Tom Allen.

Rowe had barely squeezed off her first question to Allen when the pile-on began. As their coach spoke earnestly about one of the biggest wins in the program’s history, Indiana players stopped by as they pranced off the field.

First came offensive lineman Dylan Powell. “This is the best coach in America right here,” Powell bellowed. “Recruits: Come play for this man. Best coach in America!”

Allen barely regained himself when Javon Swinton, a freshman wide receiver, hugged his coach, knocking the headphones off his ears and displacing his eyeglasses. No sooner had Allen reaffixed his headphones and adjusted his specs than he was sandwiched by Stevie Scott III and Jamar Johnson. “Best coach in the nation right here,” shouted Johnson, oblivious that his teammate had just made the same contention.

Once again, Allen tried to gather both his thoughts and his eyeglasses. “It’s a special group doing special—” He was interrupted by a flying hug (the affectionate kind) from defensive back Tiawan Mullen. And off came the headphones.

The scene went on for more than two minutes, and it all made for a gripping bit of television. Unscripted, unchoreographed and unprompted, the players recognized the occasion as an opportunity both to create an impromptu national recruiting video and to express affection for their coach. A poignant scene that, inevitably, went viral, it also provided clear indication that both the coach and his team were not exactly familiar with joyous sideline interviews.

For decades, Indiana didn’t traffic much in wins; much less road wins, much less road wins over top teams. Obscured, as it is, by the long shadow of the school’s vaunted men’s basketball program, it’s hard to exaggerate the sustained irrelevance of Indiana football. The last time the Hoosiers played in the Rose Bowl (Jan. 1, 1968), the MVP of the game was a tailback for the other team: O.J. Simpson. Since its inception in 1899, Indiana has lost 663 games, more defeats than any other program in the nation. For years, long-suffering fans reprised the joke of Lee Corso, Indiana’s beloved coach from 1973 to 82: “We’re not very big; but we sure are slow.”

Finally, though, it’s time for an updated scouting report and a new laugh line. In 2019, Indiana went 8–5, turning in a winning season for the first time in 12 years. Then, last fall, the Hoosiers emerged as the darlings of college football: a persistent, exceedingly likable team that tied for first in the Big Ten conference wins, beating Michigan, Michigan State and Penn State (by lunging inches) along the way.

The win at Wisconsin catapulted the Hoosiers into the AP poll’s top 10, the first time Indiana had been ranked that high since Sept. 22, 1969. Allen was a finalist for the 2020 Paul “Bear” Bryant Award and was named the American Football Coaches Association’s Coach of the Year. After scant roster losses to graduation, Indiana is ranked No. 17 by the AP as the ’21 season kicks off.

“There’s still work to be done,” Allen says. “But we are building it.”

In so doing, Indiana has created a template for similarly situated Power 5 programs seeking to upgrade. (Kansas, North Carolina, Oregon State … listen up.) Plagued by a history of futility? Seeking an upgrade? Unwilling to buy players, eliminate academic admission standards or otherwise run roughshod over the NCAA rule book? Here are some pages from the Indiana playbook.

Expand your recruiting footprint

For decades, Indiana tried to harvest players from its surrounding areas but often found the fields fallow. When you’re in the same state as Purdue and Notre Dame—and share a border with Ohio, Michigan and Illinois—you’d better win. And when you don’t, you will struggle to attract local and regional talent. (To wit: This summer, 2022 prospect Gi’Bran Payne became the first four-star recruit from the state of Ohio to commit to play football at Indiana.)

That in mind, Indiana has looked for players outside the Midwest, focusing especially on football hotbeds. Allen once coached in Florida and still has considerable connections there. So it is that 21 players on the roster, including Penix, hail from the Sunshine State. Five others come from Mississippi.

“Football is a numbers game, always has been,” says Allen. “Go where the players are.”

Polish diamonds

If Indiana isn’t getting NFL-ready, five-star talent, it can still develop the players it does get over their four—and, thanks to redshirting and the pandemic, potentially five—years on campus. Talk to Hoosier players and they will marvel at their improvement since arriving to the program.

Take Micah McFadden, a senior linebacker from, you guessed it, Florida, the latest of bloomers who didn’t even make the varsity team at his high school until his junior year. He was, to put it kindly, lightly recruited by Division I schools. But since alighting in Bloomington, he added 15 pounds of bulk, subtracted time on sprints, learned the nuances of technique … and is suddenly an All-America honoree and NFL prospect. “To think about my improvement year to year,” he says, laughing out loud, “it’s been astronomical.”

To paraphrase one of Allen’s many coaching bromides, Win the weight room in the offseason; win the game in the fall. An athletic department not known for lavish spending, Indiana has invested heavily in strength, conditioning and performance, both in facilities and personnel.

It’s not been without drama. A week before 2020 spring practice, Indiana’s strength and conditioning coach, David Ballou, a former Hoosiers fullback, and athletics performance coach, Dr. Matt Rhea, were poached by Alabama. Allen was blindsided. “Nick Saban is Nick Saban,” he says. “He doesn’t call anyone. He just takes your guys.” But Allen also took it as a validation. If the country’s top program is raiding your staff, you have to be doing something right.

To find a replacement, Allen looked to the NFL and hired Aaron Wellman, who’d spent the last four years with the New York Giants. According to public records, Wellman’s annual salary of $700,000 makes him the second-highest-paid strength coach in college football (behind only Ohio State’s Mickey Marotti) and, tellingly, pays him significantly more than any Indiana assistant coach, including both coordinators. Says Hoosiers athletic director Scott Dolson, “Next to Tom, [Wellman] might be the most important hire we’ve made.”

Build it and they will come

Though late to the college football facilities arms race, Indiana now has all the wretched excess the marketplace demands. The smoothie bar. The barber’s chairs in the lavish locker rooms. The hydrotherapy pools. The catering facilities. More functionally, Indiana now has a gleaming weight room that runs the width of Memorial Stadium’s north end zone.

Unlike Phil Knight at Oregon or the late T. Boone Pickens at Oklahoma State, there is no single sugar daddy, no lone benefactor at Indiana to fund these trappings and capital improvements. Instead, the school has pulled from an eclectic donor class that includes prominent alumni with sports ties (Mark Cuban), former IU football players (Antwaan Randle El), local moguls (Ned Pfau), and figures tied inextricably to the area (John Mellencamp, whose name adorns the indoor practice facility).

Invest in the culture

When Allen began shouting and scrawling “L.E.O.” last season, players weren’t sure whether it referenced a new teammate or an astrological sign. Then Allen explained that it was an acronym for “Love Each Other.” And it soon became the team’s catchphrase, emblazoned on helmets and shouted at the conclusion of press conferences and pregame pep talks. The idea, says Allen, is that “before there’s reality, there’s mentality.” Asked, gently, to translate to English from Coachspeak, Allen explains that before a team can start making inroads on goals, the players need to establish a foundation of trust, respect and affection.

It’s easy to smudge the hash marks between heartfelt and hokey. But the players have bought what their 51-year-old coach is selling. Penix admits that, amid the alphas of a football team, all the talk of love was strange at first. “But now,” he says, “It’s the most natural thing in the world.” Asked how he would describe the vibe of the program to an outsider, McFadden says: “We have a group of guys who work hard, love each other and want to go ball out.”

Like an executive who seeks to improve morale with trust-fall exercises, Allen has been known to take a running start and crowd-surf his players. During last season’s game against Michigan, he, memorably, sliced his cheek jumping onto cornerback Devon Matthews. Not that this is new. In his previous job at Ole Miss, Allen knocked out his two front teeth jumping on a dog-pile.

“I would say he’s passionate,” says Penix. “But it goes beyond that.”

Improving the culture goes beyond the hardening locker-room bonds. It means connecting with former Hoosier players like never before. It also means embracing the state’s considerable football culture—which doesn’t trail all that far behind the basketball culture. The Colts play less than an hour up the road and are very much a part of the state’s tapestry.

Indianapolis hosted a Super Bowl in 2012 and has hosted the NFL combine every year it’s been held since 1987. “The more commitment to football, the better in the long run,” says Allen. “Imagine a kid who might be undersized [for basketball]; but, hey, you’re 6′ 2″? That’s a good-looking corner. That’s a great-looking receiver. Get those kids to play football!”

Find the right leader

This, finally, may be the biggest factor in Indiana’s whooshing ascent. Allen manages to marry buoyant optimism with a reserved, slow-rolling charisma. He is a man of faith but also a man of Midwest pragmatism. Maybe above all he is a native Hoosier. Intuitively, he knows the state, its rhythms, its history. As such, he is a low flight risk. Allen has no lifetime appointment, but he is unlikely to make a lateral move for a few extra dollars. “When it’s home,” he says, “it makes a difference.” As his boss, Dolson, puts it: “You want someone who wants to be here.”

At Indiana, this wisdom was hard-won. Like so many underperforming programs, IU football has, in the past, been seduced by brand-name figures from brand-name schools. In 2002, the Hoosiers hired Gerry DiNardo, who had made his bones at LSU. It was never the right fit and DiNardo, now a Big Ten Network analyst, was fired after three typically lackluster seasons.

In 2011, the Hoosiers hired Kevin Wilson away from Oklahoma, where he was the offensive coordinator for Bob Stoops. Wilson was supposed to bring to bear the secrets of a program that had won a national championship. But he had no ties to the state of Indiana—and betrayed little outward interest in building them—and his rub-dirt-on-it sensibilities led to accounts that he tormented injured players. Owing less to his five-season record of 26–47 than to the way he allegedly treated people, Wilson resigned in ’16 before he was fired. Wilson, who has consistently denied wrongdoing, is now the offensive coordinator for Ohio State.

Credit Wilson, however, with this: He had the good sense to hire Allen, who is everything he is not. Allen arrived in 2016 as the defensive coordinator, tasked with fixing an undersized and demoralized unit. He did so, winning the players over with mentoring, not tormenting. When Wilson departed later that year Allen was promoted, and, while he took the scenic route to get there, he had landed his dream job at his dream school. Even if he knew the history.

Growing up in New Castle, Ind., 100 miles northeast of Bloomington, Allen first started attending Indiana football games as a 9-year-old in 1979. Naturally, most ended in defeat for the home team. But—significantly—Allen also remembers waking up on Sunday mornings and watching the Lee Corso Show on local television. “He was so positive,” you’d never know they’d lost.

Allen went to New Castle High School, best known as the home to the country’s largest basketball gym. The New Castle Fieldhouse once seated 9,325—that’s more than Duke’s Cameron Indoor Stadium—and the place was filled to capacity in the mid-1980s when Steve Alford played for a championship team coached by his father, Sam. A few years later, Allen played linebacker for his father, New Castle High’s revered football coach, Thomas Allen Sr. He recalls sitting in late-night film sessions with his father and the other coaches. And then reassuring his teammates that he was no mole. “Playing for your dad is incredibly awesome,” says the younger Allen. “And it’s incredibly difficult.”

Undersized (and devoutly religious), Allen played football and wrestled at Maranatha Baptist University in Wisconsin, where he met his wife, Tracy. After graduation, hell-bent on becoming a coach, he set off on his coaching odyssey. He spent 15 seasons in high schools, most in Indiana, before becoming the head coach at Wabash, an all-male university in Crawfordsville, Ind. He then went, mostly as an assistant, to (inhale) Lambuth University in Tennessee, Drake, Arkansas State, Ole Miss and South Florida.

“So seven states, 10 years. Kids went to eight different schools,” he says, sighing. “My wife’s the stud. We had to get the U-Haul, the players, the friends, whoever, to come help us pack. My wife got the brunt of that. Because I was usually off to the next job, working and getting ready to recruit.”

Going on six years in Bloomington, Tom and Tracy Allen live in an unpretentious home near the local reservoir, less than a mile from campus—which, per NCAA rules, means that Allen can invite recruits for home visits. The family also found their choice restaurants and bookstores and church, by what’s known locally as the “Breaking Away” quarry, on the southside of town. “Any time you have so many connections here, there’s the pressure that you want to do a great job,” he says. “You want to produce a product that people are proud of—both in how they play, how they act. I feel that weight all the time.”

And when Allen talks, as he inevitably does, about the “family atmosphere,” he means it literally. His folks regularly drive down for games. His daughter is an IU nursing student. His son, Thomas Allen Jr., is a redshirt senior linebacker. Last season Allen Jr. injured his hip in a game against Michigan State, requiring surgery. A father first and a coach second, Allen Sr. kissed his son before he was carted off, which became yet another viral moment.

“[Allen’s] a good, solid guy who fits in here,” says Angelo Pizzo, who wrote both Hoosiers and Rudy, and lives in Bloomington. “He has this calm about him. He also has that gift of leadership—you hear him speak and you want to go to battle with him.”

Allen has encouraged his players to lean into Indiana’s modest football history, to embrace the reality that they are transforming a program. On Nov. 21 against Ohio State, the Hoosiers played their worst quarter of the season, then trudged into the locker room down 28–7. Senior wide receiver Whop Philyor, another native Floridian, offered an ad hoc sermon. “This isn’t us. This is the old Indiana. This isn’t how it’s going to be anymore. We have the opportunity to win. Why not go win?” Indiana suffered its only regular-season loss that afternoon but outscored the Buckeyes in the second half, 28–14.

Allen and his players are guardedly optimistic that this fall, the team will continue its ascent in front of fans inside Memorial Stadium. But meanwhile, the renaissance narrative of Indiana football figures prominently in recruiting. It’s something akin to, Why work at an established blue chip when you can go to a red-hot start-up?

“Everybody always talks about, ‘Oh, it’d be so cool to go to … name your big-time school,’ ” says McFadden, the junior linebacker.

“But have you ever been to a school that has no history in football, hasn’t had all the hype around them, and you get to start there and build this program to something? It’s different, and it makes it that much more rewarding to be part of it.”

More College Football Coverage:

• The 25 Most Intriguing CFB Coaches of 2021

• Pat Forde’s Preseason Rankings, From Bama to Nevada

• Forty Observations About the College Football Schedule