It happened in the midst of a 10-hour lab final. A room full of neurobiology majors, donning white lab coats and rigid looks, were dissecting their animal subjects, the culmination of a long year filled with—as Nathaniel Hackett puts it—“real Hannibal Lecter stuff.”

He was 22, and up until that day Hackett felt like he was in his element, in a room full of future doctors. He’d sometimes leave these sessions bleary-eyed, meeting his family with animal blood still spattered on his shirt. They once had to wrangle a genetically mutated rat the size of a housecat. The desire to help and care for sick people was in his DNA. His grandmother Sarah was a long-time nurse and traveled to Haiti in retirement to start a family planning clinic, which mushroomed into a full-service organization for women that provides them with steady work and reliable income.

Along with pre-med aspirations, Hackett was a linebacker at the FCS school UC Davis—his father, Paul Hackett, coached for 40 years, holding the top jobs at USC and Pitt, and making seven stops as an NFL assistant. Nathaniel was also an avid hip-hop dancer, teaching classes throughout college and continuing to take lessons into his late 20s. To this day, he coaches his daughter, also a prospective dancer who has already appeared in music videos, proudly donning his “Dance Dad” shirt at every showcase and competition. But, more than anything, he loved to laugh. And he loved to walk into a room and light the place up.

So that day in the sterile atmosphere of that lab final, he decided to break the tension. He needed to perform. It was just a little prank to loosen things up. So what if a white coat gets splattered a little at the next station over? Wouldn’t everyone work a little better loosened up?

“People were upset with it,” Hackett says. “They were like, ‘This isn’t appropriate.’ And it was one of those things where it hit me. Oh, my God. When you’re out on the football field, and people are hitting each other and you’re messing with everyone and there’s all this activity instead of being locked in a lab. … I just realized, I can’t do arthroscopic surgery in front of 80,000 people.

“That moment just pushed me away.”

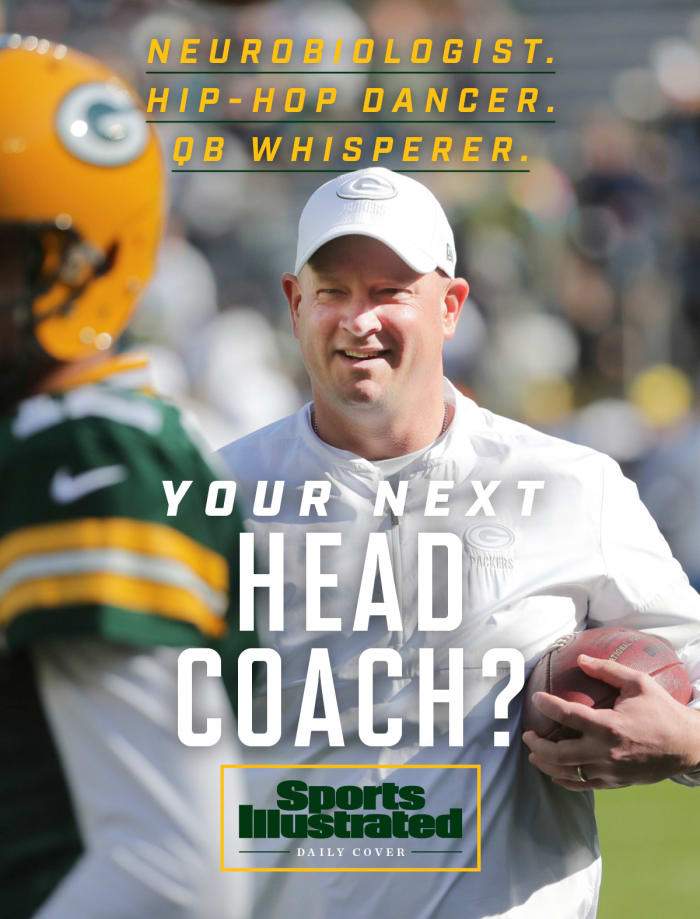

And it provided a strange—but, for Hackett, fitting—push into coaching. Over a nomadic 20-year journey, he found the stage he was searching for all along. Now the offensive coordinator of the Packers, his audience includes Aaron Rodgers, who once said of Hackett: “No one brings me more joy.” From the booth, he is Rodgers’s West Coast offense translator, and surveyor, noting when the team’s narrative game plan has punctured a soft spot in the defense ripe for a gutting deep ball. Any new prank ideas, like the one from the lab years ago, are baked into the heads of his quarterbacks, he says.

He can still dance, rising noticeably above the jumbled, white-guy-at-a-wedding fluff. His daily and weekly meetings have become legendary across various stops in college and the pros. Behind the scenes, Hackett has been the cultural energy and schematic force behind some of the biggest turnarounds in the sport. A desolate Syracuse football program became a record-setting Big East contender behind an unheralded quarterback who became an NFL draft pick. The Bills went from perpetual loser to 9–7, nudge-the-Patriots contention with Kyle Orton and EJ Manuel under center. Blake Bortles went from wayward Frisbee–throwing project to AFC title game participant, with his best numbers across the board coming under Hackett.

This offseason, the Falcons quietly interviewed him for their head-coaching vacancy, pulling the veil off football’s best-kept secret. While Hackett is not the only coach in the NFL with divergent passions and interests—he is also an avid wine enthusiast, and his love for the Austin Powers franchise has helped generate one of the Packers’ signature rallying cries—so few of them allow it all to surface, reaping the benefits of a tighter team that crystalizes around their personality. His revolution is one of joy, laughter and understanding.

“His positivity and energy, it’s infectious,” Packers left tackle David Bakhtiari says. “There has never been a day where I have not seen him come in without greater energy and enthusiasm. He’s literally a walking culture.”

A few decades ago, when Hackett decided that his life would be fun and football would be fun and that work would never be a drag, he also made the unconscious declaration that meetings under his watch would be, strategically, memorable.

Part of this was Nate. Here he was in front of a room, and he couldn’t help but get swept away. Watching him in his element is a little like seeing Robin Williams do standup; there is a frantic energy, a beautiful storm of sounds and gestures. There is a man completely absorbed by the moment.

But part of it was psychological. Meetings tend to suck. There is a person yakking on. In football, particularly, coaches tend to lose players en masse as they dissect an opposing defense inside a darkened auditorium with all the vocal energy of a sleep-meditation-app voice artist. When Hackett walks into a room, it is like a live-action comic book panel. One can almost see the speech bubbles with various onomatopoeia pouring from his mouth.

At Syracuse, players remember Hackett once backed an entire meeting to a song by the comedy troupe Lonely Island (once it was clear the somewhat cantankerous Doug Marrone was not around). He would pause, giggle and emphasize his own double entendres regularly. He’d replace the photos of rival defenders with those of stars from classic sitcoms.

“I remember when I got into coaching, part of it was understanding that there was going to be cultural change in how people present and how you’re going to teach people,” Hackett says. “You can’t just go up there and draw on the board. You’re going to need things that stimulate the guys more. That’s how the brain reacts and holds on to different things. How people think and how people operate, teaching just like you would when you’re in high school, people need references to remind themselves.”

Hackett, talking to EJ Manuel, helped the Bills to a surprise 9–7 finish in 2014.

Kevin Hoffman/USA TODAY Sports

While this all seems like low-hanging comedic fruit, Hackett was teaching college students, so he played the part (sometimes the quarterbacks would come to his house for dinner and compete in cornhole matches that lasted well into the night). The team rarely blew assignments or missed calls because they were named funny, innocently juvenile things, backed by some neuron-firing connection to an inside joke they laughed about during the week.

In front of children, he is gregarious and transforms his voice, pulling from a seemingly endless library of sound effects. In front of professionals, he is whatever the moment calls for; it’s somewhat prickly territory for most coaches who find themselves stabbing in the dark with a heap of garbled, motivational jetsam. Hackett, though, always seems to understand his audience. It is rare to talk to a former player who has been coached by Hackett that didn’t remember some deep conversation on a topic that had nothing to do with football.

Bakhtiari, who found himself recently listening to a Neil deGrasse Tyson podcast on good teachers, immediately thought of Hackett.

“He talks about teachers, and what defines a good teacher compared to a bad teacher,” he says. “A bad teacher will always blame the student or the group or the person for not obtaining information rather than reflecting or looking at yourself, finding a way to reach not only the masses but every single person. You can grab their attention and help them learn the material no matter how dry, easy, complicated or in-depth it might be. That personifies his teaching habits.”

Charley Loeb, a former quarterback at Syracuse who now coaches the position as a private tutor, says he met Hackett before the team even knew he had been hired as the new position coach. (Hackett, eventually, became offensive coordinator and tight ends coach in addition to his quarterback-coaching duties.) Hackett tracked down Loeb in the team’s field house unannounced and yanked him into an empty office, where he immediately started showing him the footwork necessary to get Loeb out of the pocket faster. They’d known each other for approximately 30 seconds, but Hackett had already seen all his practice film and compiled a dossier.

He was fearless despite being a first-time play-caller. Once, after a miserable off-location practice at the Fort Drum military base, Hackett decided the offense was getting whooped in practice. So, two weeks before the season, he called a meeting, scrapped the entire playbook and installed a Jim Kelly–era Bills K-Gun offense. Ryan Nassib, the quarterback at the time, set school records for completions and yards, and tied the school record for touchdowns in a season.

On the headset during games, he would sometimes answer the booth phone in character, in a kind of faux-Texan drawl to make his jittery quarterback laugh. Awright you slick sum’bitch, let’s go get this.

A Bills player remembers Hackett designing a play so sinister that they ran it over and over during a no-huddle surge against the Jaguars. At the line of scrimmage, the call was “Bob,” and, after a few consecutive gains, the players asked Hackett whether they should start calling it something else, lest the defense start catching on.

O.K., call it Robert.

You don’t think they’re going to catch on?

Who cares? They can’t stop us anyway.

The full Hackett experience often comes in drips. Maybe during a banal argument he utters with unbreakable confidence that the cytoplasm sits outside the nuclear membrane, followed by, yes, an explanation that he was maybe going to one day be a doctor. Once, Loeb remembers a player telling the coach he was “full of s—” after Hackett mentioned that he was a great hip-hop dancer. It was a trap his players often fall into, like the time he dragged some of his players at Stanford to his weekly dance class (he continued to take lessons throughout his first job with the Cardinal), leaving them shredded to pieces—and memorably sore—after the session. In front of the player at Syracuse, Hackett began spinning on the floor in a full-on break routine, rendering the rest of the room speechless. It was in these moments that, players say, they felt a stronger connection to their coach. Hackett was unafraid to be himself in a sea of Belichickian cosplayers all attempting to be seen as the World’s Most Serious Dude.

“When I’m coaching I try to be like him in so many different ways,” Loeb says. “Like, say it’s the middle of August, the middle of camp, you haven’t seen anything but football personnel for the last two weeks, and he’ll make that meeting really fun. He had this special power to make everything fun but just be as smart as he is.”

To measure himself, Hackett once asked his father, Paul Hackett, to watch him run a meeting in Buffalo.

Paul is one of the game’s true good guys, a generous soul who, like Nathaniel, built a career out of listening to others and being personable. But afterward, he was confused.

“I didn’t know what was going on,” he told his son. “I didn’t know if you were yelling or screaming or laughing or telling jokes or what was happening.”

Nathaniel smiled. Exactly what he was going for. This is not just a meeting. This is an experience. This is a stage. You’re here to learn. You’ll learn better if you’re having a good time.

It’s 7:45 p.m. on a weeknight in Louisville, and Eric Wood, the Bills’ long-time stalwart center, wants the journalist on the other end of the phone to know that he’s got two kids that need baths before bedtime and the whole house is wild and that there was no way he was answering a phone call or text message if the name Nathaniel Hackett wasn’t in there. He’d do anything for Nate, even delay the single moment of peace a parent gets at the end of a chaotic day.

Once, during practice, Wood needed Hackett’s attention and began yelling for him 30 yards away. His voice was lost underneath the practice speakers, screaming coaches and whistles, so he grabbed a football and hurled it at his coordinator as hard as he could, hoping the warning shot would land nearby and rouse him out of another conversation. But, wouldn’t you know it, the ball drilled Hackett right in the groin and dropped him in front of the entire team. In the military industrial complex that is football, this is the kind of accidental defiance that earns a team windsprints at best. At worst, some passive-aggressive erasure from the roster.

But a few hours later the two were fine. When Hackett and the Packers came to Buffalo this preseason to play the Bills, Hackett snuck into the radio booth where Wood was calling the game and bearhugged him during a break in play.

The point here is important: Hackett isn’t soft on his players. He just didn’t need to run the team ragged because any pain inflicted on their coach is pain they share. (Wood legitimately felt awful about throwing the football. He still feels terrible about it almost a decade later, bringing it up out of some search for catharsis.) And therein lies the core of what Hackett has accomplished at the NFL level. His temperament and philosophy have earned him a loyalty few coaches enjoy.

“He can relate to anybody,” Wood says. “He can relate to people because he treats them well. In life, you want to be treated well and encouraged and feel important. Nate is empowering with his words.”

Before joining the Packers, Hackett’s previous stop was in Jacksonville, where he helped guide Blake Bortles to a career year.

Roy K. Miller/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

Marcedes Lewis, the Packers’ tight end, enjoyed the greatest game of his career under Hackett when the pair were in Jacksonville together—a three-touchdown performance against the Bills in London back in 2017. Hackett took the time to learn about how Lewis came off the ball, and how Lewis enjoyed the physical aspects of blocking and releasing. So Hackett designed subsections of the offense to feature Lewis shooting off the ball the same, mechanical way, initiating contact until they could seize an opening. Lulling the defense into the belief that Lewis was always going to come off the ball that way, Hackett was able to create chunk passing plays when he would suddenly spring from his typical motion into wide-open field. Even last year as the Packers’ second tight end during his age-36 season, Lewis was averaging more than 10 yards per reception. His first catch of 2021, at age 37, went for 19 yards.

“That was all Hack just moving me around,” Lewis says, adding that Hackett still makes him feel appreciated for every timely block that may otherwise get lost in the flow of a game. “He knows how to plug guys where they need to be on offense.”

Green Bay’s offense often unfolds like a Netflix miniseries. There is a story to each gameplan but there are subplots; the development of a play for Lewis or some Rodgers bomb that will land in the hands of a receiver miles beyond the back end of a defense and jar the audience from a power nap induced by stretch-run plays. Hackett, in his role, is like the fixer. He is plotting and tracking the development of all these miniature powder kegs that will explode when the opponent is most vulnerable. His experience as a young coach hardwired in the West Coast offense was instrumental in getting Rodgers on board with an outside-zone system that can sometimes feel predetermined and stale to control-obsessed passers used to having the offense fit their various whims. His presence added a personality and heft to one of the most popular and copied schemes in football, helping Green Bay stand on its own amid a field of imitators.

And, once a week, Hackett helps his team celebrate those collective wins on Fridays during their gold-zone meetings. (In football parlance, the red zone is used to describe plays inside the 20-yard line. Hackett switched it to the gold zone to parlay his love of the Austin Powers villain Goldmember, a Dutch character obsessed with peeling off his own skin made of the precious metal who utters the phrase “I love goooooooold” throughout the movie.) The meetings feature a Hackett-produced video mix of plays that accentuate the best of their scheme and highlights interspersed with clips of Mike Myers as Goldmember.

Last year, during a win over the Panthers, Rodgers snuck into the end zone for a rushing touchdown and was soon joined by Davante Adams and Aaron Jones for the celebration. The three of them bent their elbows and stretched their hands toward the sky, bellowing: “I loooooooooove goooolllllllldddddd!”

Where were you the moment life began to fit together? Did you notice the almost cosmic melding of your past into the future? A time when everything you loved poured into your present moment?

When Hackett left the lab determined to make his life in coaching, he began toiling under then Stanford coach Buddy Teevens, best known as the tech-savvy, forward-thinking current coach at Dartmouth. Hackett sent out more than 30 graduate assistant applications and heard back from two schools, both telling him no. A coach who had worked with Hackett at UC Davis was coaching at Stanford and got his résumé into a pile, where Hackett could intern as an assistant for both the offensive and defensive coordinators. He knocked Teevens over in an interview. He met the coach’s wife and was hand-selected as the intern allowed to babysit the couple’s children when they went out. “The kids loved him,” Teevens says.

(Coaching Plan B was to retake a few classes to qualify at a master’s program at Cal, where he could have ended up on the same team as a teenaged Aaron Rodgers.)

At Stanford, he was handed a jumbled mess of playbooks and other information that he organized using some of the same database-building tools and drawing programs that had helped him through his neurobiology major. He rose quickly, with Teevens allowing him to wear both offensive and defensive headsets on game day. He still had enough time to take dance classes at night.

Somewhere along the way, this nomadic existence began to make perfect sense. Without the skills he picked up studying neurobiology there would be no rise in the coaching business. Without the lab final there would be no realization that coaching was his true calling. Without the background as a dancer, there would be no theatrical edge to his performances, which is how Hackett still sometimes refers to his preparation for weekly meetings. Without the humility you develop as a coach’s son, as a dancer, as an FCS linebacker, there is no realization that our time in the sun can be short-lived, so why not be yourself? Without that self-confidence, there is no Austin Powers and Lonely Island at the meetings. Maybe no perma-smile on the face of his quarterback, his best offensive weapons and a trail of former players who still remember the time they all had a blast doing something as banal as rattling off the different types of trees they could use in various audibles Sunday.

Without this full life, there is no Hackett on this summer afternoon, lamenting the decline of laughter in football, recalling, with a belly laugh, the time he saw one of his players in training camp get his car tires removed and hung on a goal post. Of course it’s a grind, he says. Of course you need to take it seriously. But there are times when the universe is telling you to let go and smile. That this is where you belong.

• Why the NFL’s Trendiest Offense Is Harder to Copy Thank You Think

• Orlando Brown Jr. Followed His Father and Forged a New Path

• Dak Prescott’s Heal Turn

• How the Bucs Are Leading a Linebacker Revival