Excerpted from It’s Better to Be Feared: The New England Patriots Dynasty and the Pursuit of Greatness. Copyright © 2021 by Seth Wickersham. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Company, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Mike Vrabel was at the NFL combine on February 29, 2020, when he looked up at a television and saw Tom Brady and Julian Edelman sitting courtside at a Syracuse basketball game with Jimmy Fallon. Something about the scene struck Vrabel as odd. It wasn’t that they were at a random college game at the Carrier Dome. It was their hair. Two pretty men looked slightly prettier.

Vrabel texted them: Hey, did you guys get highlights for the basketball game?

Rather than texting a response, Edelman FaceTimed Vrabel. Brady, of course, used to highlight his hair. But that was a long time ago, and now age had done its work around the temples. Edelman’s hair, though—it was suspiciously golden, vaguely boy-bandish. Edelman clapped back at Vrabel, yelling with the crowd behind him. Cameras caught it all, and with Brady’s free agency looming, it set off a round of social media babble. Was Vrabel recruiting Brady to join Tennessee?

A camera zoomed in on them. Edelman looked at the lens and said, “He’s coming back!”

Brady forced a smile behind clenched teeth, shaking his head.

After the game, Brady and Edelman were ushered to a VIP room encased by black curtains and filled with 20 or so donors and famous alums. This was never really Brady’s scene, but he was gracious if not enthusiastic, posing for pictures, glad-handing and small-talking. A Syracuse junior named Sean Dorcellus observed Brady, hoping to get a chance to be a part of the small talk. When a donor wanted to talk about the Syracuse game, or the Dome, or just about anything else, Brady stared intently and chitchatted. But the moment anything New England was raised, even the championships, Brady shut down, not even faking a smile, subtly steering his attention to the next lurking fan. As always, Brady’s demeanor expressed what he refused to say.

Soon, it was Dorcellus’s turn. He introduced himself, telling Brady how much he appreciated the quarterback’s statement on Kobe Bryant, who had died in a helicopter crash in the hills northwest of Los Angeles a month earlier, along with his daughter Gianna and seven others.

That got Brady’s attention, and he locked in on Dorcellus, tuning out the rest of the room. Bryant’s death had deeply affected Brady, a peer gone so young, and he spent many nights in tears, missing the idea of Bryant as much as Bryant himself. He felt that they shared a mentality, an internal drive few could comprehend, much less understand, and Bryant’s death reaffirmed Brady’s desire to play football. He knew that day might come for him at any time, so why not do what he loved? The morning of Bryant’s funeral, Brady posted a short essay titled “What’s Really Important?” It was five paragraphs—long by the standards of Brady, the king of the two-sentence email—and it was one of the first times Brady had something meaningful to say about something other than football. Dorcellus had been moved to learn that one icon drew inspiration from another, and he said that the third paragraph—on the effect Kobe had on those around him, how he could make people feel special through a mere interaction—hit him especially hard.

Now Brady was in a position to do that himself. He looked at the credential dangling from Dorcellus’s neck and asked what he did. Dorcellus, still an undergraduate, explained that he was a part-time staffer in the Syracuse athletic department, trying to figure out what to do after graduation. He wanted to be in sports. Should he work for a team? An agency? A league? A big decision loomed.

Brady enjoyed talking about things that were real, and the idea of a new beginning energized him. For weeks, he had deflected all talk of his future—even when Ben Affleck and Matt Damon joint-texted him, asking about his plans, Brady responded with a shrug emoji—but over the next few minutes, he opened up to a college kid. He gave Dorcellus the classic advice of picking a career that he loved—but then told him something he’d learned over the course of two decades in professional football: It might not be enough to just love your job. You had to want to live in the world the job created. Working with people you like, a tribe with a common goal, would make your professional life far happier than any accolade, salary, or a company’s prestige could. You need to do the work you love at a place you love with people you love.

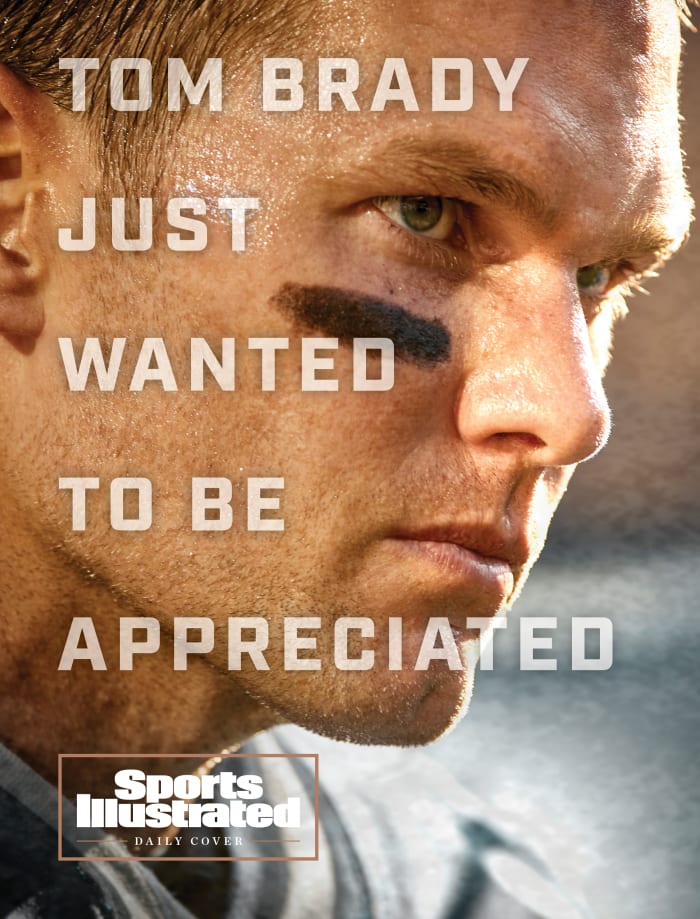

You have to feel—Brady repeatedly returned to this word—“appreciated.”

As free agency neared, Brady was alone in the house his family had mostly vacated, pondering his future. Don Yee was still his agent, but Brady was also acting on his own, quietly putting out feelers himself, leaving owners and executives to wonder if he had a free-agency plan. No matter how many hints those close to him dropped to reporters—ESPN’s Jeff Darlington said on air that he would be “stunned” if Brady returned to the Patriots—few around the league seemed to believe he would ever leave New England. Many of the executives who did due diligence found that Brady was so driven by an animus toward Belichick that they couldn’t tell whether he actually was seeking a fresh start or he just needed leverage to force Kraft to step in. But Kraft had told friends at the Super Bowl that New England wanted Brady—though maybe not until he was 45 years old. Brady had been underestimated his entire life, and now two of the men who knew him best, knew what he was capable of, were treating him as so many had before. They should have known better.

Brady was going to play until 45. It was nonnegotiable. As long as he could perform—“When I suck, I’ll retire,” he’d said—he was going to give it everything, as he always had.

Brady did not force confrontations, and neither did Belichick, but he also wasn’t one to bluff. He and Belichick spoke on the phone, not about a new deal—Belichick acted as if Brady was still under contract, which was technically true until March 17—but about potential roster improvements. The call left Brady underwhelmed, and served as a reminder that nothing was going to change in New England. Bill was Bill: he looked for bargains, not splashy imports. Brady began the call wanting to leave, and felt no different after it.

Ever a list guy, Brady jotted down what he desired in a new situation, 20 or so things: warm weather—he was sick of the cold, and so was his wife; proximity to his son Jack, who lived with his mom, Bridget Moynahan, in New York—or out west, near his parents; A two-year contract for a total of $50 million, not an outrageous demand, as it would make him only the eighth-highest- paid quarterback for 2020; a team that was already good, and whose coach valued collaboration.

A good team, not a great one. Brady was not necessarily chasing a seventh ring. That surprised those closest to him. Maybe when the season came around, his compulsion to win would take over. But right now, Brady simply needed something different for the final chapter, and in late February, he tried to assert control. He reached out to Wes Welker, who was now the 49ers’ receivers coach, and let him know that if San Francisco was interested, it would be his choice—no free-agency tour, no bidding war, full stop; he would end his career where his love of football began, in scarlet and gold, allowing his parents to drive to games for the first time since the 1990s.

At first, the 49ers didn’t buy that Brady was truly interested. Regardless, signing him would be complicated. Jimmy Garoppolo might have garnered a few Super Bowl MVP votes if San Francisco hadn’t collapsed late against the Chiefs, giving up 21 points in the final six minutes. Still, with just over two minutes left, down 24–20, Garoppolo had a chance to pull off what he had watched Brady do twice on the biggest stage, a chance to separate himself forever with a Super Bowl–winning drive. It started off promisingly, with two completions. But then Garoppolo missed three straight passes and was sacked on fourth down, effectively ending the game.

Brady rarely failed in those moments. He knew it, and he knew that the 49ers’ coaches knew it.

The 49ers were tepid, but realized they had to listen. One of the greatest football players of all time, capable of elevating an entire building with his preparation and mentality alone, was offering his services. Kyle Shanahan instructed the offensive coaches to watch all of Brady’s 2019 throws. He did so himself, turning his Cabo vacation into a film session. San Francisco executives quietly reached out to a few friends around the league, asking about the logistics of acquiring an aging future Hall of Famer—and what Garoppolo might fetch in a trade. A first- and a third-round pick? That seemed high, the 49ers learned.

The conversations didn’t stay quiet for long. Reporters wondered if Garoppolo was on his way out. The 49ers’ coaching staff had quiet doubts about Garoppolo, even before the Super Bowl, feeling that it took an inordinate amount of energy to get his head ready for game day and that he perhaps lacked Brady’s extreme drive for excellence. In the playoffs, Shanahan had called plays like a coach with limited faith in his quarterback, leaning heavily on the running game. Some in the building felt that Shanahan was too hard on Garoppolo, causing him to play tentatively. The coaches liked Garoppolo personally—and so did his teammates, enough to elect him captain—but Shanahan was open to the idea of an upgrade. But then, almost as fast as the 49ers’ interest in Brady rose, it died. The coaches liked Brady’s film—but didn’t love it. He was better than Garoppolo, they thought, but not that much better—not so much that it was worth trading away a locker-room leader, not to mention one who was nearly 15 years younger and coming off a Super Bowl appearance. A few days before free agency began, the 49ers decided to stick with their guy. This time, Garoppolo won.

In early March, the world stopped. A contagious new virus was spreading across the globe, overwhelming hospitals, taking people who thought they had the flu, producing images of goodbyes over FaceTime and, soon enough, of trucks lined up in New York City filled with body bags. Some states went into lockdown. The NBA, NHL and Major League Baseball suspended their seasons. March Madness was canceled before it began. The NFL was lucky—there are no games in March, even though some owners and fans wouldn’t be opposed to the idea—and moved forward as many companies and organizations did: over Zoom. Free agency went virtual, which meant no tour for Brady—no fancy dinners, no reporters tracking his plane, no NFL version of the contest for LeBron James. He didn’t mind. After 20 years, he had visited almost every stadium and had traded enough gossip to know each organization’s dirt. A tour would be a ridiculous fuss, and if there was anything Brady hated, it was fuss.

With the chance to pick his football home for the first time since high school, Brady faced a set of narrowing options, just as he had in 1995. Tennessee signed the resurgent Ryan Tannehill to an extension worth a guaranteed $91 million, picking a journeyman over a living legend, a decision that would have been unthinkable a year earlier. The Raiders, now in Las Vegas, planned to put in a call, but even though Brady had spoken with Mark Davis ringside at a fight in January—and even though UFC president Dana White, a Patriots fan, told the press that “if that dude isn’t playing for Boston, he’s playing here”—neither Brady nor the team seriously considered one another.

The market for the greatest quarterback ever, once rumored to include up to 10 teams, ended up constituting the Chicago Bears, Los Angeles Chargers and Tampa Bay Buccaneers. And, of course, the New England Patriots. Just past noon Eastern on March 16, two days before free agency, the league’s legal tampering period began and Jason Licht, the Buccaneers’ general manager, called Yee. Licht had worked in the Patriots’ scouting department two separate times, and had been in the draft room in 2000. He believed Brady wouldn’t leave New England, but it was worth a shot.

“You made a good decision to call,” Yee said.

Licht hung up feeling unexpectedly encouraged. From the outside, the Bucs were a strange fit: an un-iconic franchise for an icon, with an all-time winning percentage of .387—the worst across all American professional sports teams. But Tampa Bay checked a lot of Brady’s boxes: sun and warmth, easy flight for Jack, major talent on both sides of the ball in need of a missing piece, an offensive-minded head coach in Bruce Arians, who had spent a career not only fostering a collaborative environment, not only fixing cocktails after games for staff and players, but nurturing and learning from some of the game’s best quarterbacks— above all, Peyton Manning. For Brady, going to Tampa would be like converting from Catholicism to hedonism. He watched film of the Bucs, taking notes on Arians’s offensive style and on their dynamic receivers.

By the end of the day, Brady had ruled out only one potential suitor. He had been mentally gone from New England for a long time, but there was one thing left to do.

Early in the evening of March 16, Tom Brady texted Robert Kraft and asked if he was up for a socially distanced visit. Kraft told Brady to come over. With Brady’s contract due to void the following afternoon, Kraft assumed this was good news—that Brady wanted to quietly negotiate a new deal, just the two of them, just like old times. Brady drove the four minutes to Kraft’s house, and sat in his living room to deliver news that he had imagined delivering for a long time.

Brady told Kraft how much he loved him, how much he appreciated what they had accomplished, but . . .

“We’re not going to continue together.”

Kraft seemed surprised. Maybe it was the idealist in him. Maybe he didn’t want to admit how badly things were broken. Both men started to cry. Kraft stared at Brady, thinking back to that skinny, confident kid carrying a pizza in 2000. Brady thanked Kraft for all that he had done for him and his family. They spent hours in conversation. By 9:30, it was time for Brady to go. There was no hug and kiss goodbye, not during a pandemic.

Brady hoped to visit Belichick to get out in front of his own news. But Belichick said he wasn’t available—Brady told friends he thought that was telling—so they spoke by phone. It was a good call. Belichick told him he was the best player he’d ever coached—“best player the league had ever seen,” Brady later recounted to a friend—and that it was a privilege to coach him. It was a good way to end their run together. Their relationship was permanently altered as they talked. They were no longer overlord and star employee, but two individuals who together had accomplished something unprecedented.

Later that night, Brady wrote two statements: one for the fans, one for the organization. He read them over FaceTime to Jim Gray, cruising through the fan statement. But when he read the one about Kraft, Belichick, and his teammates—“I couldn’t be the man I am today without the relationships you have allowed me to build with you”—he teared up, unable to continue. A silent minute passed. He finished, and in a social media announcement at 8:44 the next morning, under the headline “Forever a Patriot,” Brady informed the world that he would not be forever a Patriot after all.

Brady had cycled to an emotional place from which he insisted, both publicly and privately, that his departure wasn’t rooted in acrimony. He wasn’t angry with anyone, he told friends. He believed he was departing on good terms. That was important. He no longer wanted to be a robotic soldier, the embodiment of an oppressive culture he’d helped create and had now lost faith in. He was free to be himself, and he saw his true self as ready to find out if there was another way to win outside of Belichick’s methods. But the morning of Brady’s announcement, Kraft spoke with Patriots beat writers to explain the loss, leaving the NFL Network little doubt as to why Brady left. “Think about loving your wife, and for whatever reason, there’s something—her father or mother—that makes life impossible for you, and you have to move on.” A few days after Brady signed with his new team, he wrote an essay for the Players’ Tribune, focused on endings and beginnings. He thanked Kraft by name. He didn’t thank Bill Belichick.

Buy It’s Better to Be Feared: The New England Patriots Dynasty and the Pursuit of Greatness

Two days after Brady’s long talk with Kraft, at about 4 p.m. on March 18, he connected with Licht and Arians on a call. The Bucs had prepared a sales pitch, calling it Operation Shoeless Joe. “Build it, and he will come” was the running joke. They had studied Brady’s film and listened to his performances when he had been wired for sound or caught venting on the sideline by cameras to try to find clues about his mindset. Unlike New England, the Bucs had weapons: a long, Randy Moss-like target in Mike Evans, an explosive threat in the emerging Chris Godwin, a lithe speedster in Scott Miller. There was also a rumor that Rob Gronkowski was considering stepping out of retirement to join Brady in Tampa.

Licht paced in Arians’s kitchen as he spoke with Brady. Arians looked on. It was going well, from their perspective. Brady asked Licht if the wideouts were good guys, one ex-Patriot to another.

“No doubt,” Licht said.

Brady seemed sold—and started to pitch himself to them. He had studied the roster, even the defense, and the entire NFC South division. Licht didn’t know Brady well from their New England days, but at least one aspect of him hadn’t changed, despite all of the wins and fame and glory and ego: He was earnestly grateful. Years earlier, an associate had emailed Brady a copy of a Michael Lewis speech called “Don’t Eat Fortune’s Cookie.” It was a dissertation about luck, and how loath successful people are to admit its role in their lives. “Don’t be deceived by life’s outcomes,” Lewis said. Brady had built his incomparable career by amassing control over an uncontrollable game, attempting to all but eliminate luck. I once asked him whether he ever paused to consider randomness in his career, the little breaks that went his way—the Tuck Rule—and his face tightened, as if insulted. But something about Lewis’s speech resonated with him, cutting to his core. “Wow,” he said after reading it. “Now that was awesome.” He now felt fortunate that a team believed in him—and eager to reward it.

After about 45 minutes, Licht handed the phone to Arians. The coach stated his view that they had a Super Bowl team. They needed someone to help them believe. You come, Arians told Brady, and we will win the Super Bowl. Arians described his offense and how much he valued collaboration. “I always let my quarterbacks have a say in what we’re doing,” he said. “I’ve always given my quarterbacks leniency, and”—he emphasized, as if to make clear—“you’re Tom Brady.”

Arians was getting fired up, and when he gets fired up, he starts to cuss. Licht watched as his coach dropped f-bombs with startling frequency, even by NFL standards, like lemmings off a cliff, and hoped that Brady wasn’t put off by them. Brady loved it all. Before the two-way pitch call with the Bucs ended after 90 or so minutes, Arians handed the phone back to Licht. The GM had one more issue to raise. “It’s a small thing,” Licht said, “but when you’re here, it could be a big thing.” It had to do with jersey numbers. Chris Godwin was Tampa’s number 12.

“Yeah, I know that,” Brady said. “I don’t care what jersey I’m wearing. I just want to win a Super Bowl. I’m actually thinking about No. 7. Is seven available?”

“I think so,” Licht said. “Why seven?”

“Go after that seventh Super Bowl, that’s pretty cool.”

Godwin ended up handing over No. 12, but Licht was excited: He knew where Brady’s mind was. Licht and Arians adjourned to a local restaurant, sitting outside, six feet apart, and looking at each other in disbelief. Brady kept saying “we” during the call, which Arians took as a good sign.

Brady heard a pitch from the Chargers, but it only confirmed that Tampa was the right spot. On March 20, Brady sat in his kitchen, wearing a black hoodie, and signed a new contract. Jack snapped a picture from across the counter. Within weeks, Brady’s people applied to trademark the phrase “Tompa Bay.” Many football minds wondered how Brady would fit with Arians, not only in terms of coaching style, but of playing style. Would the high wear off if the losses piled up? Might Brady miss the pain? Would Arians’s offensive motto—“No risk it, no biscuit”—bother a quarterback whose genius was rooted in identifying and taking the highest-percentage play? That was for tomorrow. Today, Brady looked happy and relieved as he signed his name in black ink.

• Two Generations of Gores

• Nathaniel Hackett: Neurobiologist, Hip-Hop Dancer, Your Next Head Coach

• Orlando Brown Jr.: The Son of Zeus Forges a New Path

• Justin Tucker Will Rock You (Or Sing You a Sweet Aria)