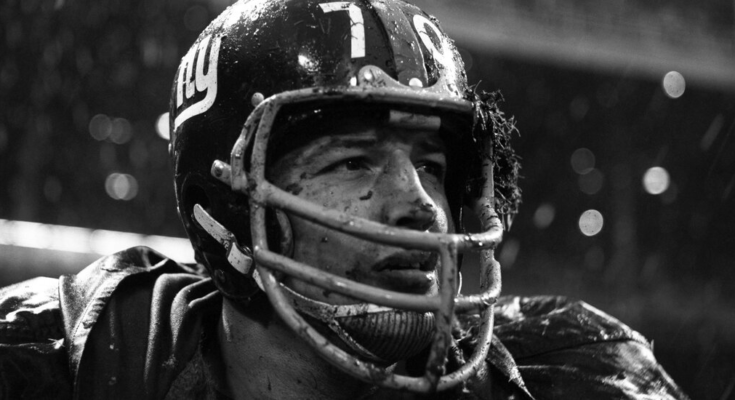

Sam Huff, the Giants’ Hall of Fame middle linebacker who became the face of pro football, his feats celebrated in the national news media, when the N.F.L. began to vie with major league baseball as America’s No. 1 sport, died on Saturday in Winchester, Va. He was 87.

His death, in a hospital, was confirmed by his daughter, Catherine Huff Myers, who said Huff learned he had dementia in 2013.

Playing for the Giants in their glory years of the late 1950s and early ’60s, Huff came out of the West Virginia coal country to anchor a defense that gained the kind of renown that had previously been reserved for strong-armed quarterbacks and elusive runners.

He played in six N.F.L. championship games in his eight seasons with the Giants. He was named to the all-league team three times and played in five Pro Bowls.

Huff was remembered for his head-on duels with two of the game’s greatest fullbacks — the Cleveland Browns’ Jim Brown and the Green Bay Packers’ Jim Taylor — but he also had 30 career interceptions. He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1982.

Yankee Stadium, the Giants’ home at the time, reverberated to chants of “DEE-fense” and “Huff, Huff, Huff” in the late 1950s as one of the N.F.L.’s oldest teams became a glamorous franchise, vying with the baseball Yankees for media acclaim in America’s communications capital.

Huff became the epitome of the rough-and-tough football star.

On Nov. 30, 1959 — almost a year after the thrilling sudden-death N.F.L. title game between the Giants and Baltimore Colts had launched pro football’s ascendancy — Time magazine placed a portrait of Huff on its cover. He was the focus of “A Man’s Game,” an article in that issue about pro football.

Huff’s fearsome aura was sealed on Oct. 30, 1960, when Walter Cronkite narrated the CBS documentary “The Violent World of Sam Huff,” part of the series “The Twentieth Century.”

A microphone and a transmitter had been placed on Huff’s shoulder pads for an exhibition game against the Chicago Bears in Toronto the previous August.

Viewers saw and heard Huff calling signals in the huddle, then threatening a Bears receiver he considered to be taking liberties with him. “You do that again, you’ll get a broken nose,” Huff warned. “Don’t hit me on the chin with your elbow. I’m not going to warn you no more.”

Burton Benjamin, the documentary’s producer, later recalled in an article for The New York Times that the “violent world” reference “quickly became a part of the football lexicon.”

As Frank Gifford, the Giants’ Hall of Fame running back and receiver, put it in his memoir “The Whole Ten Yards,” Huff became “a household name.”

Robert Lee Huff — he could not recall how he came to be called Sam — was born on Oct. 4, 1934, in Morgantown, W.Va., the son of a coal miner. He grew up in a mining camp known as Number Nine, outside Farmington, W.Va.

Huff was an All-American at West Virginia University, a 6-foot-1-inch, 230-pound guard and tackle on both offense and defense. The Giants selected him in the third round of the 1956 N.F.L. draft.

As a rookie, Huff played in the Giants’ 47-7 victory over the Bears in the 1956 N.F.L. championship game, and he became a key figure in the 4-3 alignment — four down linemen and three linebackers — installed by the Giants’ defensive coordinator, Tom Landry. Replacing the 5-2 scheme commonly used, it put Huff at the heart of the action.

“Before, I always had my head down, looking right into the center’s helmet,” Huff recalled in his memoir “Tough Stuff” (1988, with Leonard Shapiro). “Now I was standing up and I could see everything, and I mean everything. I always had outstanding peripheral vision. It’s one of the reasons I was so perfectly suited for the position.”

The Giants’ outstanding defensive linemen — Roosevelt Grier and Dick Modzelewski at tackle, Andy Robustelli and Jim Katcavage at end — kept blockers away from Huff, helping him to stop running plays. And he ranged back or moved toward the sidelines to break up passes, complementing the superb defensive backs Emlen Tunnell, Jim Patton and Dick Nolan.

Huff “almost single-handedly influenced the first chants of ‘Defense, Defense’ in Yankee Stadium,” John K. Mara, the Giants’ president and chief executive, said in a statement on Saturday.

Following their championship season of 1956, the Giants won five division titles between 1958 and 1963, but they lost in the championship game each time.

The Giants decided to reshape a veteran team following the 1963 season, when they won a third consecutive division title. They traded Huff to Washington for Dick James, a smallish running back, and Andy Stynchula, a defensive end.

Huff was shocked and angered, and the two players acquired by the Giants did little for them. As the Giants’ aging stars departed, the team descended into mediocrity. Huff gained retribution with Washington’s 72-41 victory over the Giants in November 1966, which he once called “the one game I wanted the most.”

He played for Washington from 1964 to 1967, then retired, but he came back for a final season as a player and linebacker coach when Vince Lombardi was named Washington’s head coach in 1969.

Huff was later a longtime radio broadcaster for Washington games and a marketing executive for the Marriott hotel and resort chain. He also bred thoroughbred horses.

Besides his daughter, Catherine, he is survived by his partner, Carol Holden; a son, Joseph; his former wife, Mary Helen Fletcher Huff; three grandchildren; and a great-grandchild, the family said. Another son, Robert Jr., died in 2018. Huff’s marriage ended in divorce in the late 1980s.

For anyone unfamiliar with “The Violent World of Sam Huff,” the man in the middle of the Giants’ awesome defense underlined his credo in a 2002 interview for the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

“I never let up on anybody,” Huff said. “I don’t think I ever quit on a play. If you had the football, I was going to hit you, and when I hit you, I tried to hit you hard enough to hurt you. That’s the way the game should be played.”

Michael Levenson contributed reporting.