Fast fashion is a growing source of carbon emissions. But those emissions could well be its undoing; carbon pollution is worsening climate change, including impacts in the heart of fast fashion garment hubs around the world.

A working paper published by Cornell University’s New Conversations Project in the School of Industrial and Labor Relations examines different ways the apparel industry might be forced to change in the wake of the global pandemic. It looks at everything from how online-only ordering is changing how supply chains operate to the possible impacts of climate change.

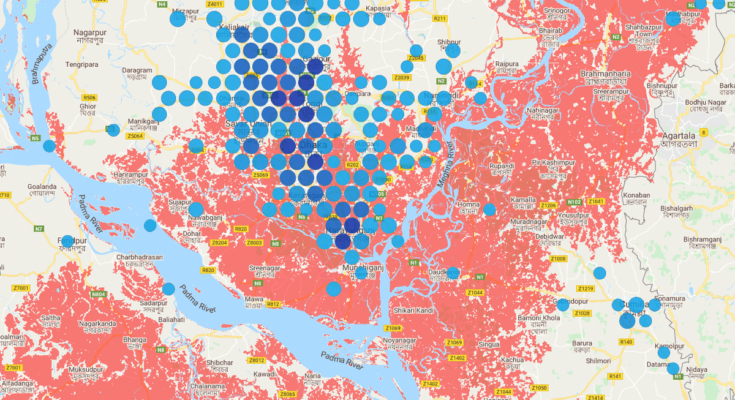

The methodology for the climate part of the study is pretty simple. Researchers from Cornell first overlaid data from Climate Central on sea level rise and increased flooding by 2030 with maps of factory locations registered with the Open Apparel Registry, an open-source database that collects and streamlines data on manufacturing facilities in the apparel and footwear sectors. The study’s authors looked at top manufacturing cities in Asia, including Dhaka, Bangladesh; Guangzhou, China; and Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. It’s overwhelmingly apparent that sea level rise is going to create a serious flooding problem in many of these key manufacturing regions; in one of the worst-case scenarios, in Ho Chi Minh City, almost 55% are in the flood zone.

A lot of the data OAR uses to site factories comes from supplier lists volunteered by fashion companies themselves. Paired with the Climate Central data, the report provides shows which brands’ supply chains—and which workers—are going to be most impacted. Just spending 10 minutes clicking around locations in one little low-lying region of the river estuary in Guangzhou, China, I found factories associated with Uniqlo, Esprit, Puma, and Ted Baker.

G/O Media may get a commission

As the paper explains, sea level rise is not the only climate threat facing garment factories. High heat can also create dangerous working conditions in crowded and non-air-conditioned factories, something that’s also a major concern for other types of factory workers, including in the U.S. While the Cornell researchers didn’t do a full analysis of how heat could impact factories, they did note that under a worst-case emissions scenario, temperatures in China could rise as much as 9 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees Celsius), while Indonesia is set to see a 95% increase in heat waves by the end of this century.

The working paper notes big brands and buyers of fast fashion generally don’t own the factories that supply their wares. That means despite the clear risks, there may be little public pressure on the factories themselves to protect workers. The opaque system has already and lack of regulation in the apparel industry has led to some high-profile tragedies.

In April 2013, a building containing five garment factories collapsed in Bangladesh, killing 1,132 people. Customers of the factories included Gap, Adidas, and Walmart. It was later discovered that the building had been built on swampland without proper permits, and the owner had refused to stop work when cracks in the building appeared. Meanwhile, 18 factories in Bangladesh were forced to close in 2017 after hundreds of workers collapsed in a heatwave and thousands walked off the job. Adding regular flooding to unstable and poorly monitored buildings—or extra heat to already-overlong working days for poor garment workers—is a recipe for potential disaster.

And even with warning signs like the ones laid out clearly in this study, big fast fashion businesses may still not be listening.

“In interviews conducted for this paper, buyers had no plans to mitigate possible large-scale losses of jobs and income due to sea level changes,” the authors wrote. “Suppliers in apparel-producing areas such as Dhaka, Ho Chi Minh City, and Jakarta revealed little anxiety about the threat of flooding and dangerously high temperatures.”