Getty Images

Hackers backed by North Korea’s government exploited a critical Chrome zero-day in an attempt to infect the computers of hundreds of people working in a wide range of industries, including the news media, IT, cryptocurrency, and financial services, Google said Thursday.

The flaw, tracked as CVE-2022-0609, was exploited by two separate North Korean hacking groups. Both groups deployed the same exploit kit on websites that either belonged to legitimate organizations and were hacked or were set up for the express purpose of serving attack code on unsuspecting visitors. One group was dubbed Operation Dream Job, and it targeted more than 250 people working for 10 different companies. The other group, known as AppleJeus, targeted 85 users.

Dream jobs and cryptocurrency riches

“We suspect that these groups work for the same entity with a shared supply chain, hence the use of the same exploit kit, but each operate with a different mission set and deploy different techniques,” Adam Weidemann, a researcher on Google’s threat analysis group, wrote in a post. “It is possible that other North Korean government-backed attackers have access to the same exploit kit.”

Operation Dream Job has been active since at least June 2020, when researchers at security firm ClearSky observed the group targeting defense and governmental companies. Bad guys targeted specific employees in the organizations with fake offers of a “dream job” with companies such as Boeing, McDonnell Douglas, and BAE. The hackers devised an elaborate social-engineering campaign that used fictitious LinkedIn profiles, emails, WhatsApp messages, and phone calls. The goal of the campaign was both to steal money and collect intelligence.

AppleJeus, meanwhile, dates back to at least 2018. That’s when researchers from security firm Kaspersky saw North Korean hackers targeting a cryptocurrency exchange using malware that posed as a cryptocurrency trading application.

The AppleJeus operation was notable for its use of a malicious app that was written for macOS, which company researchers said was probably the first time an APT—short for government-backed “advanced persistent threat group”—used malware to target that platform. Also noteworthy was the group’s use of malware that ran solely in memory without writing a file to the hard drive, an advanced feature that makes detection much harder.

One of the two groups (Weidemann didn’t say which one) also used some of the same control servers to infect security researchers last year. The campaign used fictitious Twitter personas to develop relationships with the researchers. Once a level of trust was established, the hackers used either an Internet Explorer zero-day or a malicious Visual Studio project that purportedly contained source code for a proof-of-concept exploit.

In February, Google researchers learned of a critical vulnerability being exploited in Chrome. Company engineers fixed the vulnerability and gave it the designation CVE-2022-0609. On Thursday, the company provided more details about the vulnerability and how the two North Korean hackers exploited it.

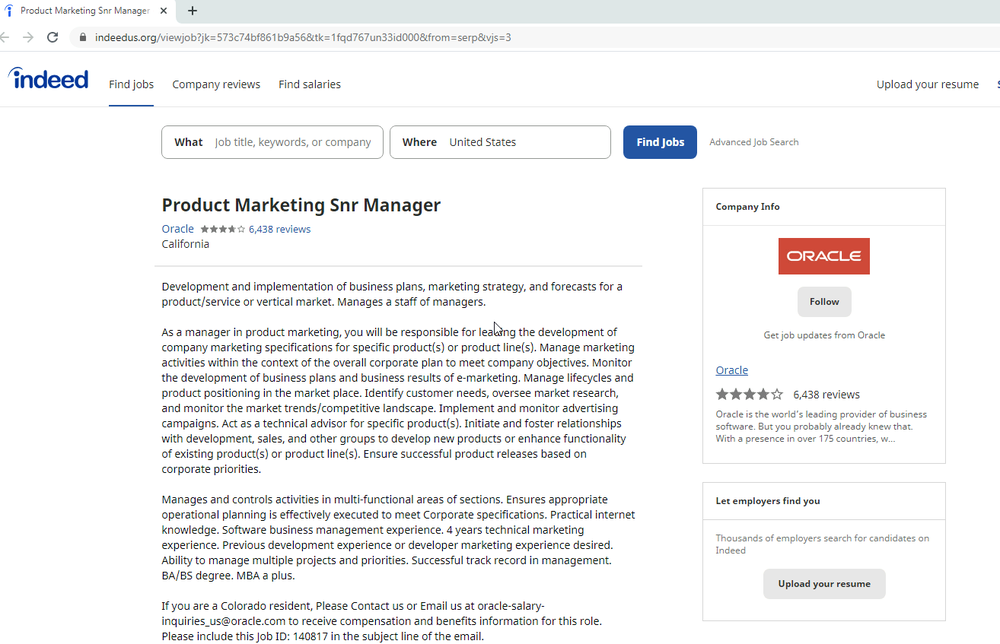

Operation Dream Job sent targets emails that purported to come from job recruiters working for Disney, Google, and Oracle. Links embedded into the email spoofed legitimate job hunting sites such as Indeed and ZipRecruiter. The sites contained an iframe that triggered the exploit.

Here’s an example of one of the pages used:

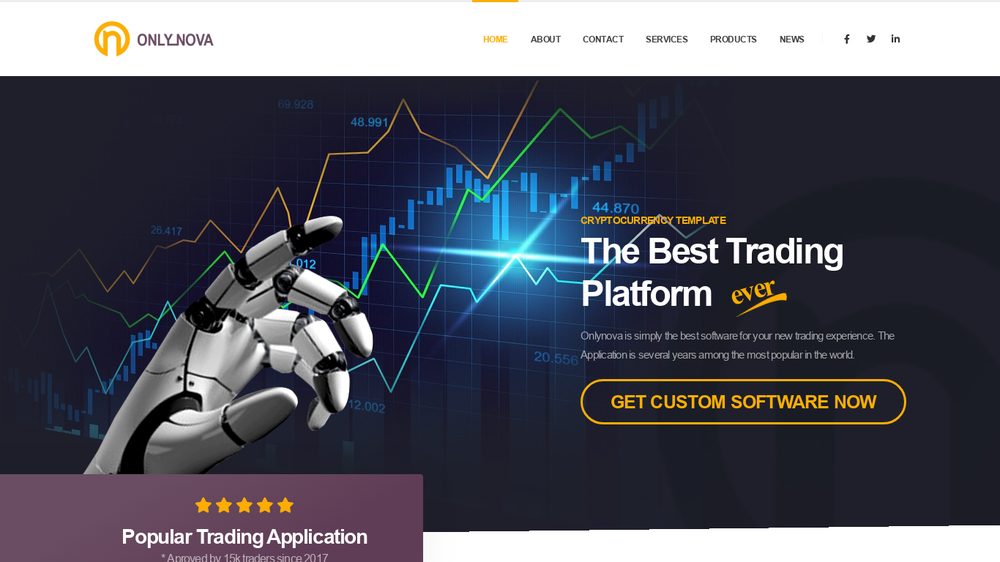

Members of Operation AppleJeus compromised the websites of at least two legitimate financial services companies and a variety of ad hoc sites pushing malicious cryptocurrency apps. Like the Dream Job sites, the sites used by AppleJeus also contained iframes that triggered the exploit.

A fake app pushed in Operation AppleJeus

Is there a sandbox escape in this kit?

The exploit kit was written in a way to carefully conceal the attack by, among other things, disguising the exploit code and triggering remote code execution only in select cases. The kit also appears to have used a separate exploit to break out of the Chrome security sandbox. The Google researchers were unable to determine that escape code, leaving open the possibility that the vulnerability it exploited has yet to be patched.