In 2009, a cadre of plaintiff’s attorneys led by Michael Hausfeld sued the NCAA on antitrust grounds on behalf of former UCLA basketball Ed O’Bannon and an as-yet-determined class.

Hausfeld had represented native Alaskans against Texaco after the Exxon Valdez oil spill. He had represented a class of Holocaust victims against a Swiss bank that held their money for the Nazis who had stolen it. Clashing with him would require a visionary NCAA leader capable of imagination, flexibility and a willingness to push the NCAA’s membership to make meaningful changes lest a wave of common sense get the NCAA laughed out of multiple courthouses and into regulatory purgatory.

Instead, the NCAA hired Mark Emmert.

In November 2010, Emmert took over as president of college sports’ governing body following tenures as the CEO at the University of Washington and LSU. The NCAA announced Tuesday that at some point between now and June 2023, Emmert will leave the office having presided over the near-complete dismantling of the organization and its once-unquestioned power. Whether that would have happened with or without him is a perfectly legitimate question. The world changed. The structure of the NCAA wasn’t designed to adapt quickly — to anything.

But Emmert cashed the (exceedingly large) checks. So he gets to wear the failure.

In a way, that was the entire point. Emmert was paid handsomely — as much as $2.9 million a year — to act as a heat shield for a bunch of university presidents who were either too greedy, too scared or too disinterested to adapt to a changing landscape and adjust the organization accordingly. At times, Emmert’s 12-year tenure felt like the 11-year period when the old World Wrestling Federation held out Canadian promoter Jack Tunney as the organization’s “president.” On TV, Tunney looked very official, and he made statements on all the major (fictional) events that affected the organization. Nine-year-old me didn’t understand that Vince McMahon was really in charge, so I yelled at the screen if Tunney handed down a decision that negatively affected Hulk Hogan or the Junkyard Dog or any of my other favorite wrestlers. Especially in the later years of his tenure, Emmert felt like that kind of figurehead. The CEOs at Georgetown or Wisconsin or Georgia or Oregon State were making — or not making — the decisions. Emmert felt as if he was just there for all of us to yell at.

Emmert did try to exercise power at first. In fact, one of his first major acts suggested he was keenly aware of the iceberg ahead. Less than a year into his tenure, Emmert held a retreat that included various university CEOs. During this retreat, Emmert pushed the idea that schools should be allowed to provide up to a $2,000-a-year stipend as part of athletic scholarships to help those scholarships get closer to the actual cost of attendance figure that the schools submitted to the federal government each year. He also voiced support for then-SEC commissioner Mike Slive’s idea to allow schools to offer four-year athletic scholarships instead of one-year, renewable ones.

“There’s a strong appetite … to find ways that allow us to be more flexible,” Emmert told ESPN in 2011. “All of our one-size-fits-all rules don’t really work when you’ve got schools as different as a small liberal arts college and a great big state university.”

Except the appetite apparently wasn’t that strong. Several leaders, most notably Boise State president Bob Kustra, voiced their disapproval of the plan. It didn’t survive an override vote, and an ever-so-tiny step toward progress was scuttled. It showed promise that Emmert saw a potential issue and worked toward a potential solution, but not being able to matriculate even that minuscule gesture across the goal line was a political failure that foreshadowed what was to come. Instead of building a consensus, Emmert allowed some shortsighted people to cause the NCAA to dig in its heels even further in the schools’ effort to keep money away from athletes even as they poured more every day into coaching salaries, athletic director salaries and questionably necessary facility improvements.

Emmert tried to grab the reins and curry public favor in 2012 when he and his hand-picked executive committee rammed through sanctions against Penn State for the Jerry Sandusky scandal. But Emmert didn’t consider several things: The NCAA had no authority to punish a school’s football program for something that was clearly a criminal matter, and going outside the usual enforcement procedure to issue such a punishment would sow mistrust from the leaders of the schools the NCAA governs.

The NCAA rolled back the penalties two years later, a few months before Emmert crony and Oregon State president Ed Ray — the chair of the executive committee — revealed in a deposition that he didn’t even bother to read the Freeh Report, which was the basis for the punishment, before issuing the punishment.

By the time those penalties were rolled back in September 2014, Emmert already had lost his Waterloo. That came June 19, 2014, in a federal courthouse in Oakland, Calif. On that day, Emmert took the stand in O’Bannon v. NCAA. The most damning part of his testimony didn’t come in an answer to a question from Hausfeld or any member of his team. Instead, it involved Emmert falling into a trap laid by the plaintiffs’ attorneys. During his cross examination of Emmert, attorney Bill Isaacson had zeroed in on the concept of amateurism as defined by the NCAA manual.

“Student-athletes shall be amateurs in an intercollegiate sport, and their participation should be motivated primarily by education and by the physical, mental and social benefits to be derived. Student participation in intercollegiate athletics is an avocation, and student-athletes should be protected from exploitation by professional and commercial enterprises.”

Shortly after, Judge Claudia Wilken cut off Isaacson and started asking her own questions of Emmert. This was a bench trial, so Wilken — not a jury — was the arbiter. The word “exploitation” in that context clearly struck a nerve with Wilken. It led to this exchange:

Wilken: What do you mean that student-athletes should be protected?

Emmert: “There’s no shortage of commercial pressures to utilize student-athletes in promoting commercial products.”

Wilken: Do you consider that to be exploitation of them? Or is it just something you don’t want?

After this exchange, plaintiffs’ attorneys followed by showing everyone in the courtroom a series of photos showing college athletes either wearing or standing in front of corporate logos. One photo showed the entire Kansas State football team running across a Buffalo Wild Wings logo. The message was obvious. The schools and Emmert’s NCAA were happy to have college athletes promote commercial products as long as the schools or the NCAA got the money instead of the athletes themselves.

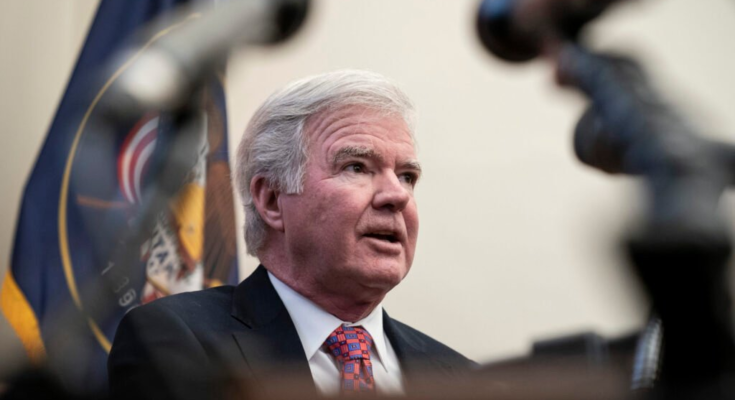

NCAA president Mark Emmert testifies in Washington during a Senate hearing a month after the Ed O’Bannon ruling in 2014. (Pablo Martinez Monsivais / Associated Press)

The NCAA should have offered to settle in that humiliating moment. Emmert should have pushed school leaders to understand that people who hadn’t been indoctrinated by decades of NCAA propaganda could see right through every flimsy argument the NCAA’s attorneys had in their (tiny) toolbox. This included federal judges. Before he flew home from Oakland, Emmert should have been on the phone to his executive committee with a message: “We’re screwed. We need to start giving the athletes more now or our entire organizational structure is going to get annihilated.”

He especially should have known this because when he had walked out of that courthouse the previous day, sports law’s version of the Terminator had walked in. Following the Wednesday portion of the trial was a status hearing for other antitrust cases against the NCAA. The plaintiffs in one case were represented by Jeffrey Kessler, who years earlier had helped bring free agency in the NFL. Just as in that case, a sports governing body was claiming that giving more to the athletes would destroy the business. Kessler had watched the NFL grow and grow following its loss in McNeil v. NFL. He had no doubt a system that gave college athletes more wouldn’t mean the end of college sports.

Why did he know this? Because the governing bodies — be they Major League Baseball, the NFL or the NBA — always said this, and they had always been proven stupendously wrong. Emmert would have been wise to remind his constituents of this. But either because they refused to budge, because he refused to budge or because Emmert lacked the political wherewithal or force of personality to convince them they needed to try to negotiate, the school leaders who actually make the NCAA’s decisions dug in their heels and tried to take on Kessler on his home turf.

We know how that turned out. That case, Alston v. NCAA, ended with the NCAA getting skunked 9-0 in the U.S. Supreme Court. Though the ruling only dealt with the narrowly focused matter before the court — NCAA rules that placed limits on “educational” expenses for athletes — the less forceful-but-still-potent majority decision and the fire-breathing concurrence from justice Brett Kavanaugh were clear: All of the NCAA’s rules were subject to antitrust scrutiny, and any rule challenged in the federal court system ran the risk of being declared illegal.

At the same time the Alston case hurtled toward its lopsided conclusion, Emmert’s NCAA managed to do something that seemed impossible: It united politicians on the left and the right in one of the most divided times in our nation’s history. Blue states — citing workers’ rights — and red states — citing free markets — passed laws that essentially made the NCAA’s rules against players making money off their name, image and likeness rights illegal. This was a classic case of pigs getting fat and hogs getting slaughtered. The schools had been so unwilling to give the athletes even an inch on this front that the public — which had seen TV contracts and coaching salaries balloon — got fed up. Dunking on the NCAA became the easiest win possible for state lawmakers.

When California became the first state to pass such a law, the NCAA put out a press release. It claimed the schools would adjust the NCAA’s rules accordingly so that further state intervention would be unnecessary. As happens in nearly all NCAA stories, a blue-ribbon committee of athletic directors and other administrators was formed. That committee did meet. Its members took their charge seriously. But nothing ever came of their work. Ultimately, Emmert’s NCAA punted on NIL rules and allowed a patchwork of state laws to go into effect.

While all that went on, a pandemic engulfed the world. The NCAA quickly canceled its championships in spring 2020. But that summer brought fighting among the conferences about what to do in the fall. In August 2020, when the Big Ten and Pac-12 postponed their seasons indefinitely while the ACC, Big 12 and SEC plowed ahead, it became abundantly clear. No one was in charge. Either because the bloated structure of the NCAA made it impossible to lead or because he just didn’t want to lead, Emmert had abdicated. But he kept cashing the checks.

Suddenly, between the rapidly shifting NIL landscape and the schools’ fear to make new rules or enforce existing ones lest they get dragged into federal court, college sports faced the most transformative time in their history. Strong leadership was more important than ever. In April 2021, as if trying to prove it hadn’t been paying attention at all the previous 10 years, the NCAA’s board of governors — a group of university presidents and other leaders — extended Emmert’s contract through 2025. That mistake was corrected Tuesday.

Now more than ever, college sports needs a visionary leader capable of imagination, flexibility and a willingness to push the schools to make meaningful changes. If that passage looks familiar, it should. You read it at the start of this column. The only difference is that all the references to the NCAA have been removed. Because in the wreckage left behind following Emmert’s tenure, an entirely new governing body might be best for everyone involved.

(Photo: Drew Angerer / Getty Images)