This week, Timor-Leste celebrates 20 years of independence. On 20 May 2002, the United Nations formally handed power to the new Timorese government and, thus, to its people.

It ended a struggle often described as spanning the 24 years from the Indonesian invasion in 1975 to the UN referendum in 1999. But before Indonesia’s bloody and brutal occupation, there had been four centuries of colonial Portuguese rule.

A government report estimated more than 102,000 people died during Indonesia’s reign, while Amnesty International has put the figure at as many 200,000. Most died from starvation and illness, but tens of thousands were killed or disappeared, and one researcher estimates 15% of the civilian population of Timor-Leste, then known as East Timor, was killed from 1975–80.

Pro-Indonesia militia, armed with automatic weapons, attack supporters of East Timorese independence during a street battle in Dili. Photograph: Beawiharta/Reuters

Alex Soares is a Timorese-Australian photographer who lives in Perth. To mark the anniversary, Soares photographed and interviewed three cousins: survivors of the occupation who now live in Australia.

They spoke of fleeing into the mountains, covertly aiding the pro-independence Falintil fighters (the military wing of the pro-independence Fretilin party), torture, starvation and of the 1991 Santa Cruz massacre, where Indonesian forces gunned down at least 250 pro-independence demonstrators.

Soares says: “Each participant I interviewed recounted first-hand experiences of having suffered torture and starvation, of having had family and friends murdered, raped and made to disappear, and of losing everything during the war. Their stories are also full of hope, love and resilience.”

These interviews have been edited for clarity.

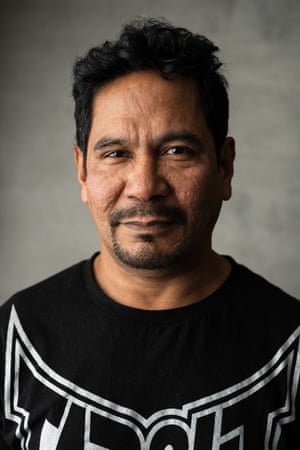

Agau, born 1967

Before Indonesia invaded our country, East Timor, we had such a wonderful life. My village, Fatubessi, was famous for the best coffee. We had a simple life. But we were very happy. We knew everyone and had work. All friends and family together. Very peaceful. Every day I played with all the other kids.

I didn’t have a childhood after 1975. When I was a kid and the adults first talked about war, I didn’t know what a war was. But then suddenly we understood it was bombs and death and fighting.

My dad always said: “No matter what, we keep fighting until we get freedom.” So all this time we travelled with Falintil and Fretilin for four years in the mountain. We would go down to the hills, hiding in the bush, go down to Maliana, Bobonaro, the large towns that border West Timor.

‘I was one of the lucky ones’: Agau. Photograph: Alex Soares/The Guardian

We’d move to the next bush, mountain. In the daytime we would sit down and rest, and at night-time we would move, crossing rivers, passing through another village. All the boys would be sent to go walk for 5-10km to see if we can find food. We’d give half to us and half to Falintil.

I lost my older brother when we were travelling near the border. We sat down and had lunch with Falintil and suddenly we were ambushed by Indonesian soldiers. They started shooting at us. We kept running. And then they just opened fire. They shot my brother. My dad and my other sisters they tried to assist him. They dug a little hole about half a metre deep. But then Falintil came past them and said, “We can’t wait or else they kill you all.” So my dad and my mum had to leave my brother. No burial.

I was already on the mountain. After two weeks alone, I found my family again and they told me: my brother had been killed.

In 1979, we were captured by the Indonesian army. We were staying in Liquiça and were ambushed. I got shot by a soldier in my lower back. I tried to hide, but we were captured. It was October or November.

Now it was my mum, dad and three siblings. Four siblings had died, two brothers and two sisters. Three of them got sick because there was no food or clean water.

My dad, who was really sick, was interrogated and tortured. He passed away shortly after that.

We moved in with our uncles and started a new life in Dili. It was my first time going to school. We started to get to know young people in my area in Dili. Some of us become estafeta [clandestine couriers who sent messages to the resistance]. We’d make contact with Falintil in the bush and organise resistance. From 1983 to 1993, my role as a young student was to help fight for independence.

In 1993, I left Timor because the situation was getting worse. I was one of the lucky ones because our family was sponsored by family who already escaped. We bribed our way to Bali and then to Australia.

After a few days of arriving in Perth, I joined with the East Timorese community in Perth to organise demonstrations. We held mass, prayed for Timor, prayed for victims, prayed for family. We grew broader community solidarity with Aussies, Christian charities. We would send funds to Falintil. At the last protest we had in 1999, there was large Aboriginal community support. At demonstrations we’d sing and scream outside the embassy.

Mito, born 1970

One day, very early in the morning, we woke up and went with all the young Timorese to mass at Motael church, the oldest in Dili.

After the mass finished, I joined all the young people in walking along the road heading towards Santa Cruz cemetery. We made a big demonstration. We were singing, “Viva Timor Leste, Viva Sebastião Gomes!” [A Timorese student who had been killed by Indonesian forces a few weeks earlier.]

I was somewhere in the middle of the group. We got to the cemetery and entered. There were lots of soldiers around but no problem at this point. They were just watching us along the road. We kept singing louder. And then suddenly they started shooting us. The protesters ran inside the cemetery.

‘Starting in Australia was a new beginning’: Mito. Photograph: Alex Soares/The Guardian

I saw people dying all around me. I was lying on the ground. Soldiers came and hit me with the butt of their guns. They hit my chest, hit my head. I was 21 years old.

After they beat us in the cemetery, they threw us in an army vehicle. They took us to Comoro [a suburb of Dili]. They shocked us with electricity: me and three friends. They tortured us. Three months after the massacre, my best fried died because of his injuries.

That night, my family thought I had been killed. All my face was black and bleeding and swollen. They couldn’t believe when I arrived back home. My mum was just crying and hugging me. She gave thanks to God, saying, “my oldest son is still alive”.

Three years later, in 1994, some family sponsored us to come to Australia. Before we left in 1994, things got worse. Indonesia was so angry with the Santa Cruz demonstrations because it made the news all over the world.

On the way to Australia, we stayed in Bali for two or three days. One aunty met us in Bali and she helped bring us to Australia. Starting in Australia was a new beginning. Everything was different. Perth was a big city for us and I really missed Timor. We left a sister and other family there. And good friends.

I got to go to Australia and start a new life. I have a good job now. I now have a family, but I could have died then. I have been back to Timor four times. But I can’t feel happy because good friends are missing. I still remember lots of trauma.

Joãozinho, born 1970

I was a little kid at that time but I can remember seeing the paratroopers coming down from the sky. My friends and I thought people were playing kites or something. But then my parents said, “No, these are not kites, these are paratroopers and we are being invaded.”

We stayed in the hills of Dare, 20km from Dili, for three months, living with other Timorese families also fleeing the violence. And after Indonesia controlled the city they began looking for a Timorese electrician to come back to town to get the power running in the capital again. We came back to Dili and my dad went back to working as an electrician.

‘All we wanted was to be independent’: Joãozinho. Photograph: Alex Soares/The Guardian

In 1980, there was a plan for the guerrilla fighters to make an assault on the Indonesian army in Dili. It was my dad’s job to sabotage the electrical system. So the night came, my dad turned off all the power on Dili but the plan had been discovered and the Falintil attack was stopped before they got to Dili. Most of the Falintil involved were killed.

The next morning, my dad was picked up by the Indonesian army. They dragged him out of our house. They took him to a torture house. They beat him, used electric shock treatment and starved him. After torturing him many more times over the next few years he stopped working. We struggled at that time for everything.

The clandestine movement very secretly organised. This was the order from the guerrillas. You can only have like one person to be in charge, to know limited information. So I would just receive a message and then pass it on. I didn’t know the full picture or why.

After the invasion we were forced to speak Bahasa Indonesian. We had no choice. Tetum [Timor-Leste’s lingua franca] was banned. If they caught you speaking Tetum you were in big trouble. Even going to work, they would stop you and interrogate you. “What you doing?” Everyone was a suspect. What can you do? You are young, they are army.

We started to get involved in a youth movement with friends around the area. We started organising things. We made a lot of demonstrations. As young Timorese, all we wanted was to be independent, we didn’t want Indonesian rule. We waited for the right time, for example when politicians or the UN visited Dili, and we protested. We wanted to show the world what was happening in Timor.

We left Timor in 1994 because my dad was really sick. He went to Australia for treatment, sponsored by family and the Timorese independence movement in Australia.

This month, 20 May, is the 20th anniversary of Timor-Leste’s independence. We always expect the leaders to run the country as we think it should be. For all people of Timor to have a good quality of life. This is what we were fighting for. For the freedom of country. And the freedom of our people.